A lungo si è ritenuto che le stelle marine non avessero affatto testa. Potrebbero essere niente altro che

1 novembre 2023

Questo articolo è stato revisionato secondo il processo editoriale e le politiche di Science X. Gli editori hanno evidenziato i seguenti attributi garantendo la credibilità dei contenuti:

- verifica dei fatti

- pubblicazione sottoposta a revisione paritaria

- corretta la bozza

da Chan Zuckerberg Biohub

Da secoli, i naturalisti si sono interrogati su quali potrebbero costituire la testa di una stella marina, comunemente chiamata "stellino". Quando si guarda un verme o un pesce, è chiaro quale estremità sia la testa e quale sia la coda. Ma con le loro cinque braccia identiche - ciascuna delle quali può prendere il comando nel far avanzare le stelle marine sul fondale marino - è stata solo una congettura su come determinare la parte anteriore dell'organismo rispetto a quella posteriore. Questo piano corporeo insolito ha portato molti a concludere che le stelle marine forse non hanno affatto una testa. Ma ora, i laboratori dell'Università di Stanford e dell'UC Berkeley, ciascuno guidato dagli investigatori di Chan Zuckerberg Biohub di San Francisco, hanno pubblicato uno studio che dimostra che la verità è molto più vicina all'opposto assoluto. In breve, sebbene il team abbia rilevato le firme genetiche associate allo sviluppo della testa in quasi tutte le stelle marine giovani, l'espressione dei geni che codificano per il busto e le sezioni della coda di un animale era in gran parte assente. I ricercatori hanno utilizzato una varietà di tecniche molecolari e genomiche all'avanguardia per capire dove venivano espressi i diversi geni durante lo sviluppo e la crescita delle stelle marine.

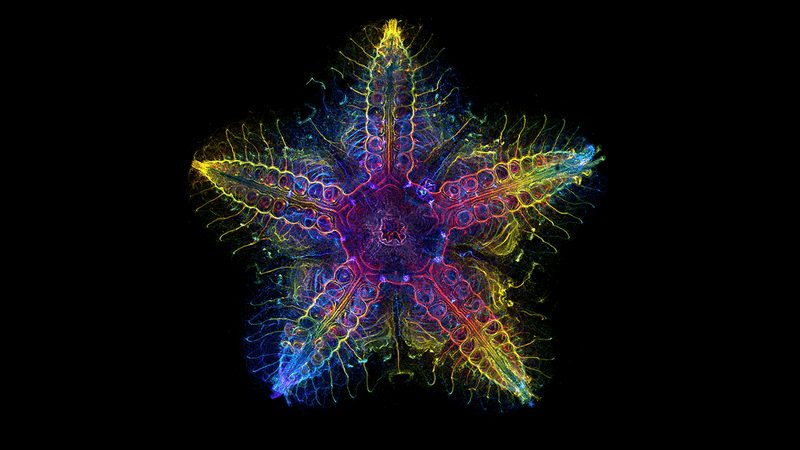

Un team a Southampton ha utilizzato la scansione micro-CT per comprendere la forma e la struttura dell'animale in dettagli senza precedenti. In un'altra sorprendente scoperta, le firme molecolari tipicamente associate alla parte più anteriore della testa si concentravano al centro di ciascun braccio della stella marina, con queste firme che diventavano progressivamente più posteriori spostandosi verso i bordi dei bracci. La ricerca, pubblicata il 1 novembre su Nature, suggerisce che, lontano dall'essere prive di testa, le stelle marine hanno perso il corpo nel corso dell'evoluzione per diventare solo teste. Micro-CT scan di una stella marina che mostra lo scheletro (grigio), il sistema digestivo (giallo), il sistema nervoso (blu), i muscoli (rossi) e il sistema vascolare dell'acqua (viola). Crediti: Università di Southampton

"È come se la stella marina non avesse affatto un torso e potesse essere meglio descritta come una testa che striscia lungo il fondale marino", ha detto Laurent Formery, studioso postdoc e primo autore del nuovo studio. "Non è affatto ciò che gli scienziati hanno supposto riguardo a questi animali". Due dei tre coautori principali dello studio, il biologo marino e dello sviluppo Christopher Lowe dell'Università di Stanford e Daniel Rokhsar dell'UC Berkeley, esperto di evoluzione molecolare delle specie animali, collaborano da dieci anni. Quasi tutti gli animali, compresi gli esseri umani, sono simmetrici bilateralmente, il che significa che possono essere divisi in due emisferi specchiati lungo un unico asse che si estende dalla testa alla coda.

Nel 1995 il Premio Nobel per la Fisiologia o la Medicina fu assegnato a tre scienziati che avevano utilizzato le mosche della frutta per dimostrare che il piano corporeo bilaterale, dalla testa alla coda, visto nella maggior parte degli animali, deriva dall'azione di una serie di interruttori molecolari, codificati dai geni, espressi in regioni ben definite della testa e del tronco. I ricercatori hanno poi confermato che questa stessa programmazione genetica è condivisa dalla stragrande maggioranza delle specie animali, compresi i vertebrati come gli esseri umani e i pesci, e molti invertebrati come insetti e vermi. Ma il piano corporeo delle stelle marine da tempo confonde la comprensione degli scienziati riguardo all'evoluzione animale. Invece di mostrare una simmetria bilaterale, le stelle marine adulte, e gli echinodermi correlati come gli urchini e i cetrioli di mare, hanno un asse di simmetria a cinque pieghe senza una chiara testa o coda. E nessuno è stato in grado di determinare come la programmazione genetica guidi questa insolita simmetria a cinque pieghe. Alcuni scienziati hanno ipotizzato che nelle stelle marine, l'asse dalla testa alla coda potrebbe estendersi dalla parte posteriore corazzata dell'animale fino al suo ventre, che è ricoperto dei cosiddetti piedi tubolari.

Altri hanno suggerito che ciascuno dei cinque bracci della stella marina corrisponda a una copia di un asse convenzionale dalla testa alla coda. Tuttavia, gli sforzi per confermare definitivamente tali ipotesi hanno affrontato sfide, soprattutto perché i metodi per rilevare l'espressione genica, sviluppati principalmente in un numero limitato di organismi modello come topi e mosche, non funzionano bene nei tessuti di giovani stelle marine. Per anni, Lowe e i suoi colleghi hanno bramato di portare informazioni genetiche a rispondere alla domanda mappando l'attività genetica nell'evoluzione delle stelle marine. Ma senza gli strumenti genetici complessi sviluppati nel corso di decenni di ricerca che esistono per gli organismi modello tipici, un'analisi così completa era spaventosa.

Lowe encountered a solution for this problem at one of the regular San Francisco meetings of Biohub Investigators, where another researcher suggested he contact PacBio, a Silicon Valley–based company that builds genome-sequencing devices. Over the previous five years, PacBio had been perfecting a technique for sequencing massive quantities of genetic material using postage stamp–sized chips jam-packed with millions of individual chemical reactors, each primed to simultaneously read long stretches of DNA captured within.

Unlike traditional sequencing, which requires chopping genetic material into small pieces to ensure accuracy, PacBio's approach, called HiFi sequencing, can pull highly accurate data from intact, gene-sized DNA strands, making the process much faster and cheaper. It was exactly what Lowe and his team needed to establish a process for studying sea star genetics from the ground up.

'The kind of sequencing that would have taken months can now be done in a matter of hours, and it's hundreds of times cheaper than just five years ago,' said David Rank, also a co–senior author of the new study and a former PacBio Scientific Fellow. 'These advances meant we could start essentially from scratch in an organism that's not typically studied in the lab and put together the kind of detailed study that would have been impossible 10 years ago.'

This technology allowed the researchers to sequence the genomes of the sea stars and employ an approach called spatial transcriptomics, through which they could pinpoint which sea star genes are active at precise locations in the organism. To search for patterns that would indicate a head-to-tail axis, the researchers examined gene expression differences in three different directions across the body: from the sea star's center to its arm tips, from its top to its underbelly, and from one side edge of its arms to the other.

Then, to get a closer look at how certain key genes were behaving, they labeled them one by one with fluorescent dyes to create a detailed map of their distribution in the sea star body.

The researchers found that neither of the prominent hypotheses of sea star body plan structure was correct. Instead, they saw that gene expression corresponding to the forebrain in humans and other bilaterally symmetrical animals was located along the midline of sea stars' arms, with genetic expression corresponding to that of the human midbrain towards the arms' outer edges.

While the genes marking different subregions of the head in humans and other bilaterians were expressed in the sea star, only one of the genes typically associated with the trunk in animals was expressed, at the very edges of the sea stars' arms.

'These results suggest that the echinoderms, and sea stars in particular, have the most dramatic example of decoupling of the head and the trunk regions that we are aware of today,' said Formery, adding that some bizarre-looking sea star ancestors preserved in the fossil record do appear to have had a trunk. 'It just opens a ton of new questions that we can now start to explore.'

Questions that the team hopes to address next involve whether the genetic patterning seen in sea stars also shows up in sea urchins and sea cucumbers. For his part, Formery also wants to look into what the sea star can teach us about the evolution of the nervous system, which, he said, no one quite understands in echinoderms.

Learning more about the sea star and its relatives will not only help solve key mysteries of animal evolution, but could also inspire innovations in medicine, the researchers said. Sea stars walk by moving water through thousands of tube feet and digest their prey by extruding their stomachs outside of their bodies. It only stands to reason that these unusual creatures have also evolved completely unexpected strategies for staying healthy—which, if we took the time to understand them, could expand our approaches to combating human disease.

'It's certainly harder to work in organisms that are less frequently studied,' Rokhsar said. 'But if we take the opportunity to explore unusual animals that are operating in unusual ways, that means we are broadening our perspective of biology, which is eventually going to help us solve both ecological and biomedical problems.'

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Chan Zuckerberg Biohub