Monica Lewinsky: Experiencing Life as a Halloween Costume | Vanity Fair

One of the many things I never thought I’d grow up to be was a Halloween costume.

Thankfully, I have never gone to a Halloween party where I’ve bumped up against, well, myself. I did, however, get an idea of what that might be like when, several years ago, I went to see the movie Made of Honor, starring Patrick Dempsey and Michelle Monaghan. It opens with a scene in which Dempsey, dressed as Bill Clinton, mingles at a Halloween party—with three Monica Lewinskys—all clad in blue dresses and berets, holding cigars. (Cringe Factor: 10.)

There’s always been interesting insight to be gleaned from Halloween costumes. At the age of eight, Camille Paglia went trick-or-treating dressed up as Napoleon. (To analyze that would require a battalion of shrinks.) Heidi Klum dashed 50 years into the future, dressing as an elderly version of herself. Me? One year (no lie) I went as Shrödinger’s Cat. These days, however, Halloween—for adults, at least—is the time we put a societal stamp on “the year in review,” as partygoers and hipster trick-or-treaters don costumes that represent the personalities that have saturated the culture and dominated our news feeds.

Given the above, the most popular costume this season should be obvious: Caitlyn Jenner. And one can naïvely envision the act of turning up as Caitlyn as a purely flattering gesture, an homage to the empowering way she emerged this past year. But as one begins to untangle that, the symbolism of the costume becomes layered—and not necessarily in a positive way. (When one costume store revealed their “Caitlyn” in late August, outrage ensued, and rightly so.) Here’s how Sarah Kate Ellis, the C.E.O. and president of GLAAD, explained it to me last week: “There are so many elements to consider here: the stereotype that being trans can be reduced to what someone wears [or] how they look; the commodification of trans identities in the face of disproportionate rates of poverty faced by trans people; and, of course, making trans women the butt of a joke, since these costumes may be worn by men whose sole intention is to imply that all transgender women are simply men in dresses.”

Her assessment points to the darker side of the Halloween costume as social commentary. And that can be particularly true when someone begins the year as a private person and ends it in the aisles of a costume store.

Kelly Osbourne has already dressed up as Rachel Dolezal (and sadly, she probably won’t be the last). Right now, outlets carry a Cecil the Lion costume and one meant to resemble Walter Palmer, the Minnesota dentist turned big-game hunter. (In protest, PETA is fighting back by offering its version: a bloodied Dr. Palmer being mauled by a plushy lion head.) Regardless of where we consider someone’s behavior to fall on our moral spectrum, we might want to take a long, hard look at whether it makes sense for society to condone mocking such people—especially those who had never intended to become part of a global conversation in the first place.

Such reservations aside, sometimes this instant-fame-to-costume transformation can be positive. I remember 2009 as the year the streets were filled with Captain Sullenbergers and 2010 as the year of the “rescued Chilean Miners.” And this Halloween, I expect another big contender to be Alex Lee, better known as #AlexfromTarget—who, last November, was a totally anonymous Target employee and now has millions of adoring followers on social media. (Although Nick Bilton points out in his New York Times piece on Alex that there has been a steep downside to his fame: including online harassment and death threats.)

Sure, we hide behind masks all the time. But the stakes are climbing higher. In the age of social media and the irresistible, almost-pathological drive to curate our images, the costumes we choose must deliver a message about who we are, how clever we are, and how fabulous our lives are. But there is a fine line between clever and cruel.

A connection exists between our true selves (hidden by a disguise) and our anonymous identities (cloaked in cyberspace). In both instances we dissemble, and even disappear. And that emboldens us and sometimes, sadly, makes us crueler and less civilized than the everyday public personae we project.

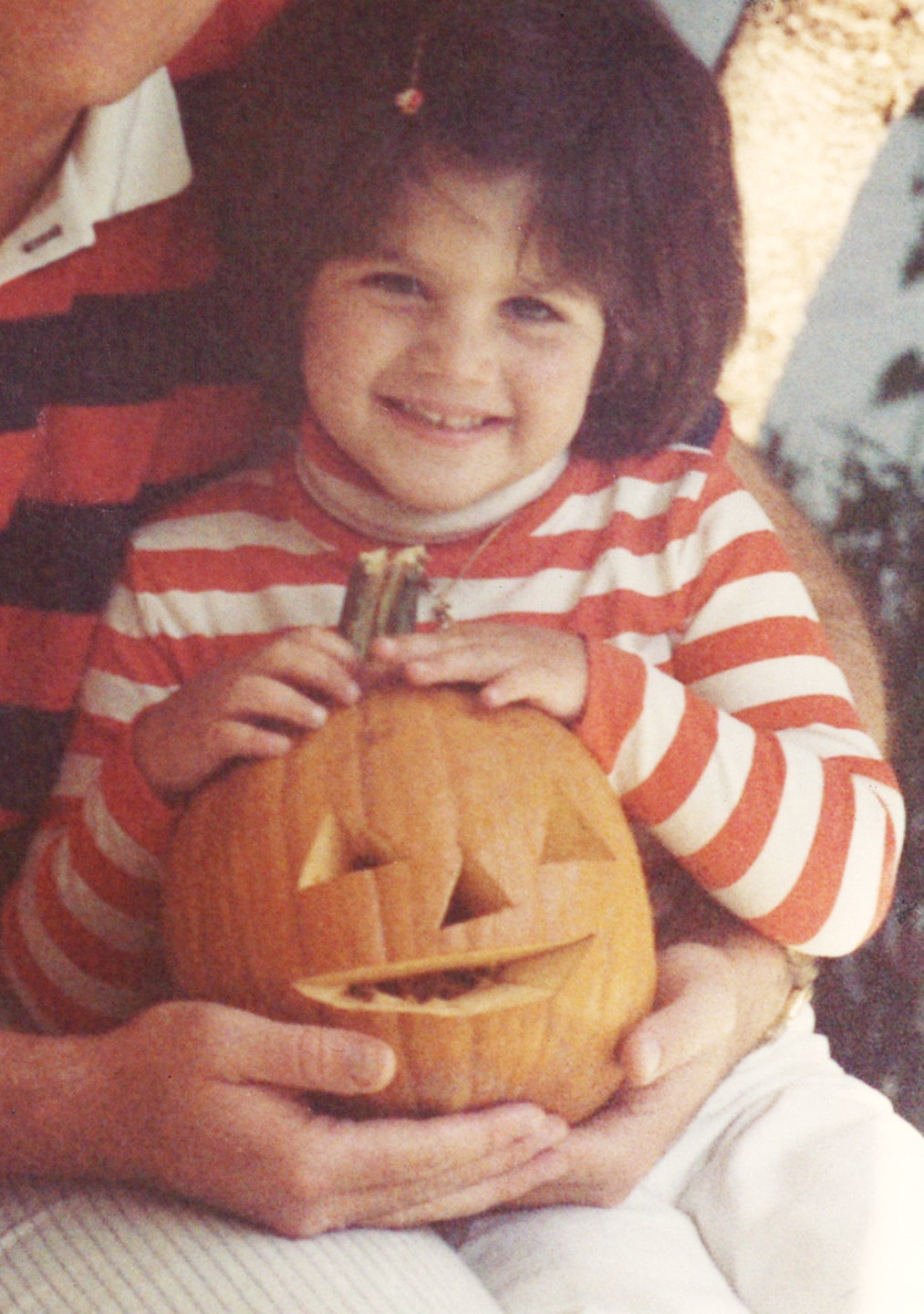

As a kid, Halloween was one of my favorite holidays. (I’m embarrassed to say that 100 percent of that had to do with the peanut-butter cups and the Laffy Taffy. I’m not alone, right?) Today, I’m still in it for the candy, but it’s the one day of the year when people seem to refrain from asking me, “Are you Monica Lewinsky?”—a question that is preceded, less and less frequently, by the charming disclaimer, “No offense, but . . .” And instead, I hear, “Great costume!”

Related: Monica Lewinsky on Shame and Survival