Millennials Embrace the Prepper Lifestyle, Aligning with Older Survivalist Generations | Vanity Fair

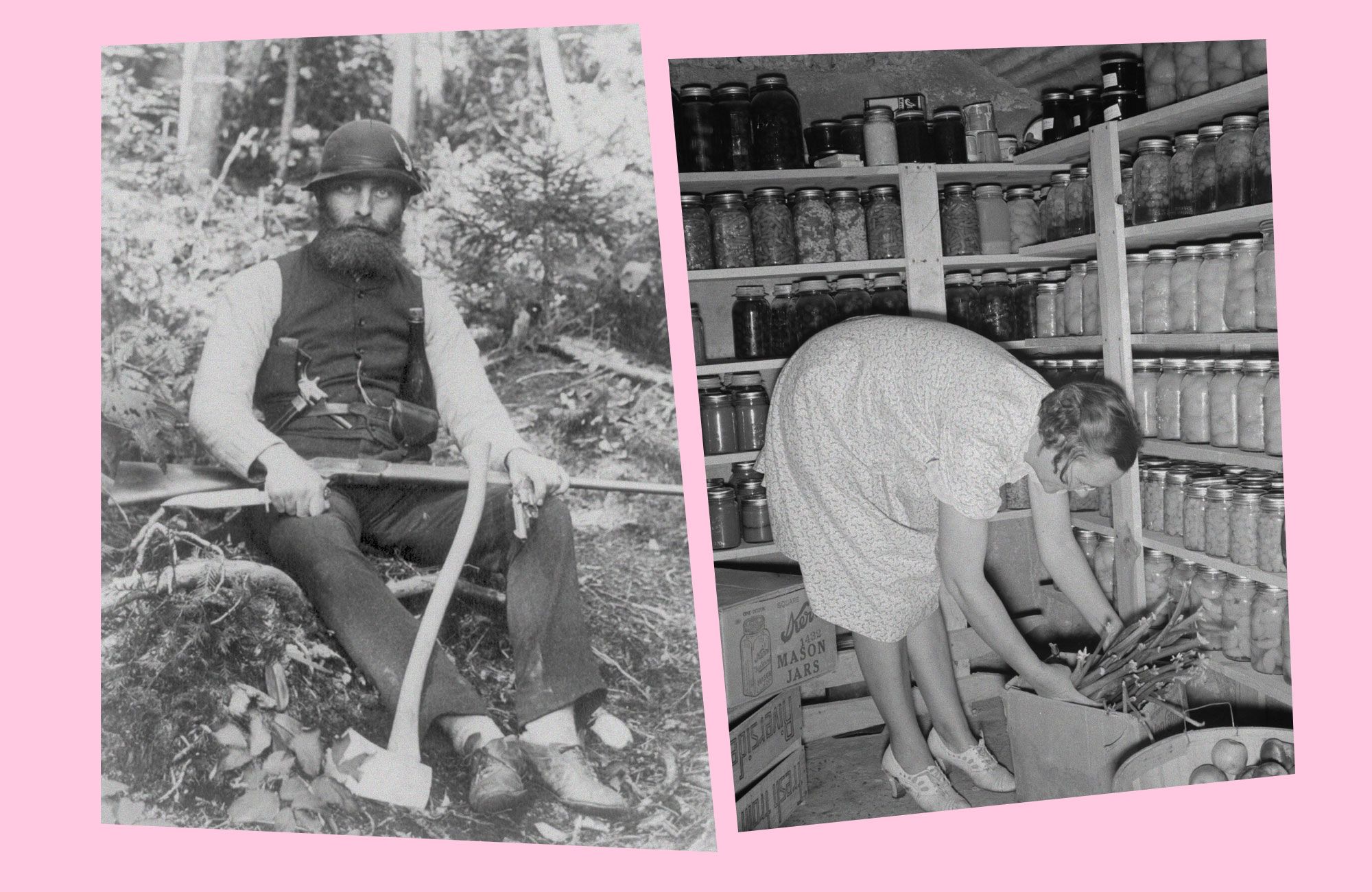

There are so, so, so, so many scenarios for the apocalypse. Natural disasters: fires, floods, tornadoes. And man-made: biochemical accidents, wars, mass shootings. The stereotype of a prepper—borne of the Cold War paranoia of the ’50s and ’60s—is a rifle-clutching, far-right Deliverance type, wild-eyed and making for the exit, mapping the quickest route to the closest bunker. And the boomer preppers are still out there. But a younger generation of preppers is growing, with and among us all.

On forums like the r/preppers subreddit, posters compare their plans for surviving when SHTF (shit hits the fan)—and their questions about firearms stockpiling and storage only serve to reinforce the individualistic, politically conservative stereotype of survival prep. In fact, “preppers” is a bit of a misnomer: Many of the posts lean more toward survivalism, the more militaristic goal of being able to live independently off the land indefinitely, while the related “prepper” aims to equip themselves and make it through to the other side. There’s often an every-man-for-himself, grizzled undertone to the survivalist community, and in fact, Kurt Saxon, who is widely credited with coining the term “survivalist,” claimed to be a member of the American Nazi Party.

However, it’s increasingly clear that as the scope of what’s considered a disaster broadens, so does the demographic of who’s preparing, and how. Tornado season still comes every year, and with it, preparations—but new, more human threats loom. Progressives, especially those of the millennial generation and younger, are bracing for disaster, not only taking courses to learn survival skills or packing go-bags, but building out non-tangible bunkers in the form of social connections, stockpiling cooperative relationships so they can lean on one another to get through. It’s the idea of community as the ultimate renewable resource for survival.

Zoë Higgins, 32, learned about basic emergency preparation out of necessity after moving to New Orleans in 2017, initially stumbling on those same hardcore forums where the oft-cited first rule of being a prepper is to never tell anyone you’re a prepper. The implication is that you’ll be targeted by those desperate unprepared folks who will do anything to get their hands on your supplies.

That didn’t sit right with Higgins, a trauma-focused social worker. She gathered her supplies, and she also “started looking into the research,” she tells Vanity Fair. “I’m like, Is it true? Are people really looting after disasters? I thought we all agreed that was a racial stereotype that was only applied to Black people and people of color in the wake of disaster, but not white people getting food for their families, right? And I was correct. And then I found all these studies about the pro-social behaviors that have been measured in the immediate aftermath of disaster, and something clicked in my brain, and I was like, this is really freaking important, and this also completely knocks off the classic prepper forum mindset of ‘everyone for yourself, you can’t trust anybody.’”

She began making TikToks under the handle @leftistprepper, and more recently started a subreddit of the same name that provides non-panicky, community-focused resources for prepping for all kinds of disaster, widespread and personal. In 2021, when Hurricane Ida hit New Orleans at greater force than predicted, Higgins and her husband evacuated to Tennessee. Her group chats and networks were lighting up: “I was seeing all these [messages]: ‘Hey, does anybody have batteries?’ ‘I don’t have fans.’ ‘My paycheck didn’t come. I couldn’t get extra diapers.’ All this stuff, right? I was like, Oh, I gotta do something.” Stores were stocked where she was staying, so she “just threw out this Hail Mary to my Instagram friends” for donations. They were able to buy supplies to help 13 families.

“What carried me through this is that we did not have to bring back a single bottle of water for ourselves, because our home was safe and not flooded, and we were prepped,” Higgins says. And I realized there’s a connection between what I’ve read about these pro-social disaster behaviors and the importance of talking about preparedness, because when I prepare, because I have the resources and privilege to do so, I am better able to serve those in my community who don't have that access.”

Rachel Kaplan, author of Urban Homesteading: Heirloom Skills for Sustainable Living, agrees. She runs down a list of some prep in place in her own home—“I do have water on hand, because I live in California, and if the water system shuts down, like, water is dire in California, right? I do a lot of canning and preserving of food, so there’s always food in the house”—but she doesn’t grow all of her own food, “never have, never will.” She does know people who can grow what she needs though, and thinks you should too.

“I think that, if we were to be honest, we could actually acknowledge that you could have what you need for a few days, but most people cannot gather what they need for an extended collapse. How do we share what we’ve got?”

She continues, “We’re in a disaster together.” And unfortunately, a weekend course, or even a YouTube video could teach you how to start a fire or identify safe berries to eat, but “it’s easier to grow food than to get along with your neighbors in general.”

Old-school prepper educators have seen an uptick in interest as well, and from a broader demographic than times past.

Shane Hobel founded the Mountain Scout Survival School in upstate New York in the late ’90s and taught after-school and community classes. Before that, he learned outdoors skills first from his World War II veteran dad; then physical survival skills from working as a stuntman and bouncer for years.

“Either you can make a fire or you can’t; either you can block a punch or you can’t,” he tells Vanity Fair of the common threads in his teaching. “There’s not a whole lot of gray area in that world.”

If it sounds like he’s of the knife-in-teeth Rambo camp, you wouldn’t be entirely wrong: Hobel maintains that having clean water and a stash of nonperishable foods and medical supplies is important for physical survival, and that skills are more paramount still. But he has seen his client base shift from predominantly lone-wolf types to more mothers, families, and groups of friends who want to support one another in times of tension and need. In addition to his regular survival skills classes, covering basics like how to start fires or find shelter, Hobel offers private consultations, which he says often take the form of discussion and planning in Brooklyn brownstones, with wine and charcuterie on offer to pair with disaster prep.

Clients are “nervous about what the future is bringing,” Hobel says. It’s not just the fires in California, the floods in Texas, the storms in New Jersey. He says their concerns are, “I can’t trust the government. I can’t trust a badge holder. I have to trust my family, my loved ones, and our skills. We have to, now, start taking care of ourselves.”

In the private consults, “I get every single walk of life, every single age, religion, race, it doesn't matter. We’re all part of the two-legged nation. And I think that’s what people are now gravitating towards: They have to realize that they can't do this on their own, that they need tribal [mindsets]. You need friends, you need community. Neighbors argue; community gets together and has a block party.”

Once those supplies you’ve stockpiled run out, it’s just you and those around you. Your social skills and connections are now essential survival skills. As of 2024, citizen trust in the US government was hovering around 22%. Uncle Sam seems increasingly unlikely to swoop in and save you.

Even FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, has been kicking the nonperishable can down the road for years and encouraging the buddy system as an important tool: In a 2018 report, the agency stated: “The work of emergency management does not belong just to FEMA. It is the responsibility of the whole community, federal, [state, local, tribal and territorial governments], private sector partners, and private citizens to build collective capacity and prepare for the disasters we will inevitably face.”

In other words: Nose goes. Just because the words “emergency management” are in the name, that doesn’t mean we should expect them to actually manage emergencies, right? As recently as June 2025, FEMA acting head David Richardson made a little jokey-joke that he “didn’t realize” there was such a thing as hurricane season, as employees sounded the alarm that the agency was “months behind” on preparing for that very thing—and as Donald Trump bellowed about wanting to bag FEMA altogether. If you were wondering, yes, NOAA has predicted that this year’s hurricanes could be “above-normal.” We’re all laughing.

Kaplan first got interested in studying permaculture and sustainable living when she became a mother, three weeks before the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Now, her child is 24 years old and tells her that their peers are also discussing mutual aid and community as first-line survival essentials in light of decreasing government services, not to mention decreasing government trust.

“As we see things collapsing—and I think it’s wise to imagine that it’s going to keep going in that direction for quite a while—the more we think about, what do we need? What would sufficiency be?” Kaplan says. It brings to mind a line from Station Eleven, itself borrowed from Star Trek: Voyager, touted as the motto of a traveling Shakespearean theatre troupe: “Survival is insufficient.” The 2021 HBO adaptation of Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel of the same name offered a fictionalized look at a postapocalyptic landscape, complete with fear, survival, and little moments of beauty and art, beamed onto the TV screens of a barely-post-COVID, traumatized real world. We survived, but we also changed. We’re more likely to have masks and nonperishables on hand now, but we also shuffled priorities and personal relationships while the very air felt like a threat. It’s not just about surviving, it’s about living. Station Eleven isn’t the only reflection of our disaster mindset in pop culture, shows like The Last of Us and Yellowjackets have also exploded, not to mention the perennial popularity of Survivor. Facing death isn’t considered novel, it’s entertaining.

Kaplan, Hobel, and Higgins all said that, over the past several years, they have seen inquiries spike in the aftermath of natural disasters and around presidential elections. Lauren Tafuri and Ryan Kuhlman, the founders of designy go-bag company Preppi, tell Vanity Fair that they see the same correlation. Their kits range from the $50 “essentials” package to the Prepster Ultra Advanced, which comes in a fire-retardant tote bag and carries a nearly $5,000 price tag. The company aims to provide emergency supplies in designy, pleasant vessels. Something people wouldn’t want to hurl into the back of a closet and would be more likely to keep close at hand. When they founded their company 11 years ago, the goal was to make preparedness more accessible and “sell the products in places that typically would never have sold preparedness products before—like Nordstrom, Urban Outfitters, Pottery Barn, that type of retailer,” Tafuri says. “It’s in spaces that people are interacting with more frequently and they don’t have to go out of their way to get the supplies that they need.”

And by providing an all-in-one starter kit that doesn’t come packaged in, say, a camouflage print ripstop bag or neon orange bucket, but a backpack made out of the same fireproof material as firefighters’ uniforms or a sturdy but cleanly designed canvas bucket bag, they hope to remove some of the scariness, and even stigma, from taking tangible action to prepare for bad things to happen. Preppi’s founders want to “get people over the emotional hump” of prep culture with a more inviting product, Tafuri says, and “take away a little bit of the scary.”

And the duo are no strangers to the importance of community in survival, either: Their offices are not far from Los Angeles’ Altadena, where fires ravaged homes in January 2025.

“We saw that FEMA was not helping these people whose homes completely were leveled,” Kuhlman says. They assembled and advertised free reentry kits, including masks to shield residents from the fumes of lithium batteries exposed to heat and other protective equipment, to distribute to residents coming back to see how their homes had fared. “We saw people on Instagram going through their rubble in, like, jeans and sandals.”

Kuhlman calls that marathon of brief interactions with hundreds of people moments before they returned to their homes, many not knowing whether they’d lost something irreplaceable, and others already knowing they had, as “the most visceral thing I’ve ever done in my entire lifetime.”

As parents themselves, Kuhlman and Tafuri do worry about the future, but say that they have hope seeing how kids act at in-person events they’ve run, where they hailed tweens as “calm and collected about [preparation]. They’re more sensible than any adults about this sort of thing,” Kuhlman says. Kids don’t show the same avoidant skittishness while discussing emergency preparedness as adults. “The world is very scary right now. I think people try to avoid it as much as possible, but the more frequently this stuff happens, sometimes you can’t ignore it.”

Higgins sees her personal preparation for things like storms and power outages, along with political disaster, as the first step toward freeing herself to help others. "Frankly, prepping for fascism is much, much, much more complicated than prepping for a hurricane," she says.

Even the Preppi founders, whose livelihoods are based on helping people stock their physical emergency supplies, know that human connection is an essential resource that cannot be overlooked.

"Worst-case scenario, you got to know your neighbors, which we all should be doing anyway," Kuhlman says. "Best-case scenario is, in the emergency, you know that Cindy down the street knows CPR, or this person's a doctor. So it's a win-win for community building in general, and community building in a sense of resilience and getting through the sorts of weird stuff that we never thought that we were going to face in our lifetime, but seems to be happening more frequently."

Exclusive: Emma Heming Willis and Bruce Willis at Home

Inside Prince Harry and King Charles's Royal Reunion

Can an All-Star Team of Broadway Vets Finally Crack Chess?

Emmys 2025: See Our Predictions for Every Winner

A Guide to Elizabeth Taylor's Luxury Diamond Collection

Jeremy O. Harris Is the Greatest Showman

Why Reality Winner Sounded the Alarm

Prince William and Kate Middleton's Real Estate Portfolio: A Guide

The 25 Best Movies on Netflix to Watch This September

From the Archive: The Armani Mystique