Come Pitagora ha trasformato la matematica in uno strumento per comprendere la realtà.

Se hai mai sentito la frase "la musica delle sfere", probabilmente il tuo primo pensiero non era sulla matematica.

Ma nella sua origine storica, la musica delle sfere era effettivamente tutta incentrata sulla matematica. In realtà, quella frase rappresenta una svolta nella storia della relazione tra la matematica e la scienza.

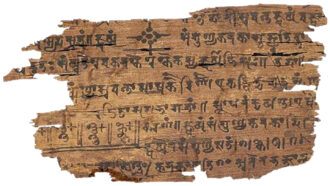

Nelle sue prime forme, come praticato nell'antico Egitto e Mesopotamia, la matematica era principalmente uno strumento pratico per facilitare le interazioni umane. La matematica era importante per calcolare l'area del campo di un agricoltore, per tenere traccia del salario dei lavoratori, per specificare la giusta quantità di ingredienti quando si preparava il pane o la birra. Nessuno utilizzava la matematica per investigare la natura della realtà fisica.

Non fino a quando i filosofi antichi greci cominciarono a cercare spiegazioni scientifiche per i fenomeni naturali (senza ricorrere ai miti) qualcuno si preoccupò di chiedersi come la matematica potesse aiutare. E il primo di quei Greci a usare seriamente la matematica a tale scopo fu il misterioso leader del culto religioso, Pitagora di Samo.

Fu Pitagora che trasformò la matematica da semplice strumento per scopi pratici in chiave per sbloccare i misteri dell'universo. Come ha notato lo storico Geoffrey Lloyd, "I Pitagorici sono stati ... i primi teorici a tentare deliberatamente di dare la conoscenza della natura una base quantitativa e matematica".

Pitagora è nato intorno al 575 a.C. a Samo, un'isola del Mediterraneo orientale vicino alla costa della Turchia moderna. Ha viaggiato molto, in Egitto e Babilonia e forse anche in Persia, per imparare come la matematica veniva utilizzata in quelle antiche culture. Potrebbe persino aver passato del tempo nella città di Mileto (non lontano da Samo) per studiare con l'anziano Talete, il fondatore dell'antico sforzo greco per spiegare il mondo razionalmente.

Intorno all'età di 40 anni circa, Pitagora si diresse verso ovest fino al sud Italia, stabilendosi nella città colonia greca di Croton. Lì ha avviato una nuova fase della scienza antica, mescolando religione, musica e matematica in un culto dedicato a vivere in armonia con la natura. Per Pitagora, ha scritto lo storico di filosofia greca W.K.C. Guthrie, la filosofia smette di essere principalmente giustificare la natura ma invece "diventa la ricerca di un modo di vita mediante il quale possa essere stabilita una giusta relazione tra il filosofo e l'universo".

Certo, se il tuo obiettivo è vivere in armonia con l'universo, devi sapere qualcosa sull'universo. Quindi, anche se Pitagora ha fondato sostanzialmente un culto religioso, lui e i suoi seguaci hanno comunque ampliato la ricerca greca per spiegare il cosmo.

E qui entra in gioco la matematica.

Pitagora credeva che, alla radice, la realtà fosse fatta di numeri. Questo sembra pazzesco alle menti moderne insegnate che la materia è fatta di atomi e molecole. Ma ai tempi antichi, nessuno sapeva davvero nulla di cosa fosse la realtà. Ogni filosofo principale aveva un'idea preferita per quale tipo di sostanza servisse da base della realtà.

Talete, per esempio, pensava che tutto derivasse dall'acqua. Il suo studente Anassimandro si ribellò, sostenendo che la realtà alla radice consisteva in un qualche materiale infinito e senza caratteristiche chiamato "apeiron" o illimitato. Anassimene, successore di Anassimandro, rifiutò l'apeiron a favore dell'aria - tutto poteva essere spiegato dall'aria che si rarefava o si solidificava. Un filosofo successivo, Eraclito, insistette sul fatto che tutto proveniva ultimamente dal fuoco.

Pitagora scelse i numeri. I numeri, insegnò ai suoi seguaci, sono i semi da cui cresce tutta la realtà. Tutti i membri del culto pitagorico dovevano recitare un giuramento che gli dava il merito di identificare i numeri "che contengono la sorgente e la radice della natura sempre fluente".

Nello specifico, Pitagora identificò la radice della realtà in ciò che chiamò la "tetractys", composta dai primi quattro numeri interi: 1, 2, 3 e 4. Sommati insieme, quei numeri danno 10. Dieci, concluse Pitagora, è il numero "perfetto", il numero che tiene la chiave per comprendere la natura.

E perché 1, 2, 3 e 4? Perché quei numeri erano la chiave per creare suoni armoniosi.

Immagina di pizzicare una corda tirata di lunghezza fissa, producendo una nota musicale. Se ne pizzichi una metà della lunghezza, ottieni un'altra nota, separata dalla prima nota di un'ottava. Se le corde sono pizzicate simultaneamente, le due note sono armoniose. In altre parole, un rapporto di lunghezza di corda di 2:1 produce un suono piacevole. In modo analogo, altri intervalli musicali armoniosi chiamati "quarta" e "quinta" rappresentano rapporti di lunghezza di corda di 4:3 e 3:2. Pitagora si rese conto che questi rapporti produttori di armonia coinvolgevano tutti i numeri 1, 2, 3 e 4. Pertanto, concluse, la loro somma, 10, era il numero chiave per sviluppare una teoria dell'universo.

Pythagoras himself may not have developed that theory fully, but his later followers produced a vision of the universe consisting of heavenly bodies revolving around a “central fire.” That fire was NOT the sun, which was just one of the other heavenly bodies. The sun shone brightly because it reflected the light from the central fire back to the Earth (and the inhabited part of the Earth always faced away from the fire).

The Pythagoreans surmised that the motions of the heavenly bodies generated pleasant music. As Aristotle later explained it, those bodies move rapidly and therefore they must make sound, because anything moving quickly on Earth makes sound (think arrows whizzing through the air). Proper ratios of the planets’ speeds (which depended on their distances from the central fire) guaranteed that the sounds would be harmonious. Hence the moving planets created a “harmony of the heavens.” Because later Greek writers supposed that each planet is carried on its orbit by a rotating sphere, eventually that harmony became known as “the music of the spheres.”

So in a sense, the Pythagoreans believed that the universe itself could be regarded as a gigantic musical instrument. As Aristotle put it, the Pythagoreans thought “the whole heaven to be a musical scale and number.”

But this picture had a problem. The Pythagoreans knew of only eight heavenly bodies: Earth, moon, sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. A ninth, outermost sphere transported the fixed stars. But to be perfect, the cosmos needed a 10th body. So the Pythagoreans proposed the existence of another planet, a “counter-Earth,” orbiting the central fire inside the orbit of the Earth. Nobody could see that planet because it was always on the other side of the fire. Rather than limit their description of the cosmos to what could be observed, the Pythagoreans resorted to mathematical theory to infer the existence of an unseen reality.

This theory was wrong, of course. But it nevertheless foreshadowed the modern use of mathematics to predict unseen phenomena. In the 19th century, for instance, James Clerk Maxwell used equations to predict the existence of radio waves. In the 20th century, Paul Dirac used math to predict the existence of antimatter. And in the 21st century, astronomers detected gravitational waves, vibrating space itself, as physicists had expected based on the math of Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Using math for understanding nature was unknown before Pythagoras. It was his idea. Previously math had been a tool for scribes or surveyors or cooks. “Pythagoras freed mathematics from these practical applications,” the Dutch mathematician B.L. van der Waerden wrote in his classic history of ancient math. “The Pythagoreans pursued mathematics as a kind of religious contemplation, as a way to approach the eternal Truth.”

As for the music of the spheres, one issue remained. If the heavens made harmonious sounds, why didn’t anybody hear them? Aristotle reported that the Pythagoreans “explain this by saying that the sound is in our ears from the very moment of birth and is thus indistinguishable from its contrary silence.”

Aristotle rejected that explanation, just as he rejected the idea of a “counter-Earth” as well as the whole notion that everything was made from numbers. And yet, the importance of numbers in science, first expressed by Pythagoras, ultimately proved to be much more resilient than most of Aristotle’s ideas. As experts on early Greek philosophy André Laks and Glenn Most have written, “Of all the early Greek philosophers,” Pythagoras “without a doubt exerted the longest-lasting influence until the beginning of modern times.”