Cómo Pythagoras convirtió las matemáticas en una herramienta para entender la realidad.

Si alguna vez has oído la frase "la música de las esferas", probablemente no pienses en matemáticas.

Pero en su origen histórico, la música de las esferas se trataba realmente de matemáticas. De hecho, esa frase representa un hito en la historia de la relación entre la matemática y la ciencia.

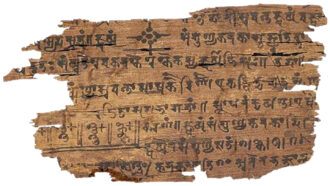

En sus formas más antiguas, practicadas en el antiguo Egipto y Mesopotamia, la matemática era principalmente una herramienta práctica para facilitar las interacciones humanas. La matemática era importante para calcular el área del campo de un agricultor, para llevar un registro de los salarios de los trabajadores, para especificar la cantidad adecuada de ingredientes al hacer pan o cerveza. Nadie usaba matemáticas para investigar la naturaleza de la realidad física.

No fue hasta que los filósofos griegos antiguos comenzaron a buscar explicaciones científicas para los fenómenos naturales (sin recurrir a mitos) que alguien se preguntó cómo la matemática ayudaría. Y el primero de esos griegos que utilizó seriamente la matemática para ese propósito fue el misterioso líder religioso del culto, Pitágoras de Samos.

Fue Pitágoras quien convirtió la matemática de una mera herramienta para fines prácticos en la clave para desbloquear los misterios del universo. Como señaló el historiador Geoffrey Lloyd, "Los pitagóricos fueron ... los primeros teóricos en haber intentado deliberadamente darle a la comprensión de la naturaleza una base cuantitativa y matemática".

Pitágoras nació alrededor del año 575 a.C. en Samos, una isla en el Mediterráneo oriental cerca de la costa de la actual Turquía. Viajó ampliamente, a Egipto y Babilonia y quizás incluso Persia, para aprender cómo se usaba la matemática en esas antiguas culturas. Incluso puede haber pasado tiempo en la ciudad de Mileto (no lejos de Samos) para estudiar con el anciano Tales, el fundador del antiguo esfuerzo griego por explicar racionalmente el mundo.

Alrededor de los 40 años, Pitágoras se dirigió hacia el oeste hasta el sur de Italia, estableciéndose en la ciudad griega de Crotona. Allí inició una nueva fase de la ciencia antigua, mezclando religión, música y matemáticas en un culto dedicado a vivir en armonía con la naturaleza. Para Pitágoras, escribió el historiador de la filosofía griega W.K.C. Guthrie, la filosofía deja de ser principalmente sobre explicar la naturaleza, sino que "se convierte en la búsqueda de una forma de vida mediante la cual se pueda establecer una relación correcta entre el filósofo y el universo".

Por supuesto, si tu objetivo es vivir en armonía con el universo, necesitas saber algo sobre el universo. Por lo tanto, aunque Pitágoras básicamente estableció un culto religioso, él y sus seguidores aún expandieron la búsqueda griega para explicar el cosmos.

Y ahí es donde entró la matemática.

Pitágoras creía que, en su raíz, la realidad estaba hecha de números. Eso suena loco para las mentes modernas enseñadas de que la materia está hecha de átomos y moléculas. Pero en tiempos antiguos, nadie sabía realmente nada acerca de lo que es la realidad. Cada filósofo importante tenía una idea favorita sobre qué tipo de sustancia servía como fundamento de la realidad.

Tales, por ejemplo, pensaba que todo derivaba del agua. Su alumno Anaximandro se rebeló, argumentando que la realidad en su raíz consistía en algún material infinito y sin rasgos llamado apeiron, lo ilimitado. Anaxímenes, el sucesor de Anaximandro, rechazó el apeiron a favor del aire: todo podría explicarse por la rarefacción o solidificación del aire. Otro filósofo posterior, Heráclito, insistió en que todo venía en última instancia del fuego.

Pitágoras eligió números. Los números, enseñó a sus seguidores, son las semillas de las que crece toda la realidad. Todos los miembros del culto pitagórico tenían que recitar un juramento acreditándolo por identificar los números "que contienen el manantial y la raíz de la naturaleza siempre fluente".

Específicamente, Pitágoras identificó la raíz de la realidad en lo que llamó la tetraktys, compuesta por los primeros cuatro enteros: 1, 2, 3 y 4. Sumados, esos números dan 10. Diez, concluyó Pitágoras, es el número "perfecto", el número que tiene la clave para entender la naturaleza.

¿Y por qué 1, 2, 3 y 4? Porque esos números eran clave para crear sonidos armónicos.

Imagínate al pellizcar una cuerda tensa de longitud fija y producir una nota musical. Si pellizcas una cuerda cuya longitud es la mitad de la primera, obtienes otra nota, separada de la primera por una octava. Si las cuerdas se pellizcan simultáneamente, las dos notas son armónicas. En otras palabras, una proporción de longitud de cuerda de 2:1 produce un sonido agradable. De manera similar, otros intervalos musicales armoniosos llamados cuarta y quinta representan relaciones de longitud de cuerda de 4:3 y 3:2. Pitágoras se dio cuenta de que todas estas relaciones armónicas involucraban los números 1, 2, 3 y 4. Por lo tanto, concluyó, su suma, 10, era el número clave para desarrollar una teoría del universo.

Pythagoras himself may not have developed that theory fully, but his later followers produced a vision of the universe consisting of heavenly bodies revolving around a “central fire.” That fire was NOT the sun, which was just one of the other heavenly bodies. The sun shone brightly because it reflected the light from the central fire back to the Earth (and the inhabited part of the Earth always faced away from the fire).

The Pythagoreans surmised that the motions of the heavenly bodies generated pleasant music. As Aristotle later explained it, those bodies move rapidly and therefore they must make sound, because anything moving quickly on Earth makes sound (think arrows whizzing through the air). Proper ratios of the planets’ speeds (which depended on their distances from the central fire) guaranteed that the sounds would be harmonious. Hence the moving planets created a “harmony of the heavens.” Because later Greek writers supposed that each planet is carried on its orbit by a rotating sphere, eventually that harmony became known as “the music of the spheres.”

So in a sense, the Pythagoreans believed that the universe itself could be regarded as a gigantic musical instrument. As Aristotle put it, the Pythagoreans thought “the whole heaven to be a musical scale and number.”

But this picture had a problem. The Pythagoreans knew of only eight heavenly bodies: Earth, moon, sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. A ninth, outermost sphere transported the fixed stars. But to be perfect, the cosmos needed a 10th body. So the Pythagoreans proposed the existence of another planet, a “counter-Earth,” orbiting the central fire inside the orbit of the Earth. Nobody could see that planet because it was always on the other side of the fire. Rather than limit their description of the cosmos to what could be observed, the Pythagoreans resorted to mathematical theory to infer the existence of an unseen reality.

This theory was wrong, of course. But it nevertheless foreshadowed the modern use of mathematics to predict unseen phenomena. In the 19th century, for instance, James Clerk Maxwell used equations to predict the existence of radio waves. In the 20th century, Paul Dirac used math to predict the existence of antimatter. And in the 21st century, astronomers detected gravitational waves, vibrating space itself, as physicists had expected based on the math of Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Using math for understanding nature was unknown before Pythagoras. It was his idea. Previously math had been a tool for scribes or surveyors or cooks. “Pythagoras freed mathematics from these practical applications,” the Dutch mathematician B.L. van der Waerden wrote in his classic history of ancient math. “The Pythagoreans pursued mathematics as a kind of religious contemplation, as a way to approach the eternal Truth.”

As for the music of the spheres, one issue remained. If the heavens made harmonious sounds, why didn’t anybody hear them? Aristotle reported that the Pythagoreans “explain this by saying that the sound is in our ears from the very moment of birth and is thus indistinguishable from its contrary silence.”

Aristotle rejected that explanation, just as he rejected the idea of a “counter-Earth” as well as the whole notion that everything was made from numbers. And yet, the importance of numbers in science, first expressed by Pythagoras, ultimately proved to be much more resilient than most of Aristotle’s ideas. As experts on early Greek philosophy André Laks and Glenn Most have written, “Of all the early Greek philosophers,” Pythagoras “without a doubt exerted the longest-lasting influence until the beginning of modern times.”