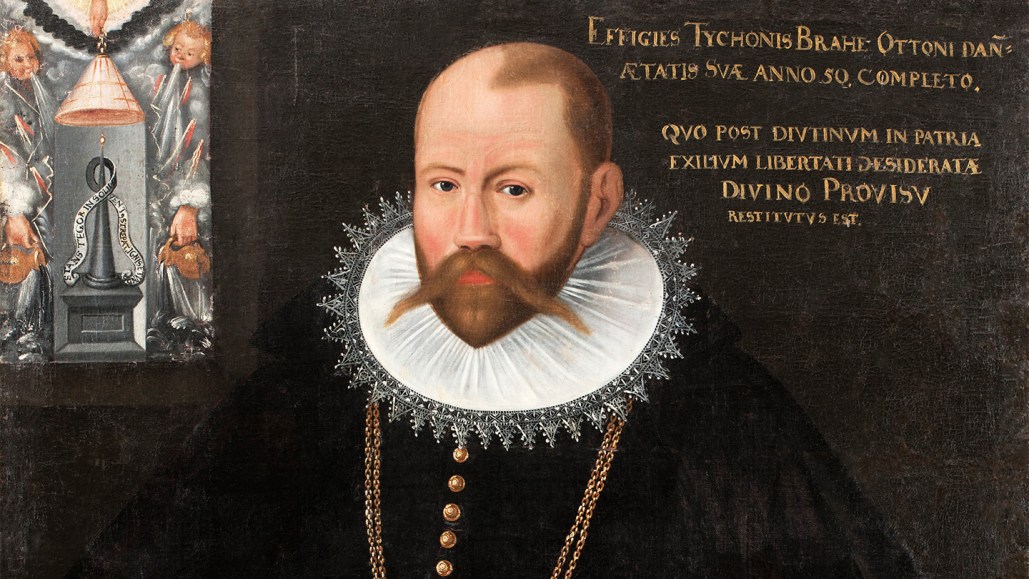

Tycho Brahe's Alchemy Revealed Through Analysis of Broken Glassware

Artifacts from the ruins of a medieval laboratory are spilling a famous scientist’s secrets.

A chemical analysis of broken glassware belonging to 16th century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe revealed elevated levels of nine metals, researchers report July 25 in Heritage Science. The finding offers tantalizing clues to his work in alchemy, a precursor to modern chemistry.

The astronomer is perhaps best known for making the first observations of supernovas and being among the first scientists to propose that Earth orbits the sun (SN: 12/18/99). But he also dabbled in alchemy. Instead of trying to make gold from less valuable elements, he developed elixirs like the medicamenta tria — a trio of medicines that contained herbs and metals.

Brahe kept his recipes secret, though, says chemist Kaare Lund Rasmussen of the University of Southern Denmark in Odense. What’s known about the medicamenta tria is based on secondhand accounts.

Rasmussen analyzed the chemical composition of the edges of one ceramic fragment and four glass shards excavated from Brahe’s lab on the Swedish island of Ven. The chemist detected high levels of mercury, copper, antimony and gold — four metals known to have been used in the medicamenta tria.

No one fragment contained all four elements. Some of those metals were found on just the exterior or interior sides, while others coated both sides. The vessels could have picked up the exterior metals from accidental splashes, or they may have been placed inside a larger vessel containing those elements, say Rasmussen and coauthor Poul Grinder-Hansen, a historian at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

The remaining five metals — nickel, zinc, tin, lead and tungsten — aren’t listed in any of Brahe’s preserved recipes. Because all five of them were found on the ceramic shard, along with copper and mercury, he may have used the ceramic vessel to collect waste, the researchers propose. Tin, lead, nickel and zinc were commonly used in the Renaissance world, Rasmussen says. “The most peculiar one was tungsten.”

Tungsten was first purposefully isolated in 1783, nearly 200 years after Brahe’s death. The metal’s presence on the shard could be coincidental, Rasmussen says. Brahe may have separated tungsten from another material without realizing it.

But there is a tiny chance that the isolation was intentional. In the first half of the 16th century, German mineralogist Georgius Agricola reported that the presence of a certain substance (later identified as tungsten) made smelting tin ore difficult. Perhaps Brahe was investigating, Rasmussen speculates.

The study is “really intriguing,” says Laure Dussubieux, a chemist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Research on ceramic vessels is common because they were often used as cookware, she says. “Much less work has been done to understand what kind of inorganic things might have been ‘cooking.’”