Ozempic Could Offer Unexpected Protection Against Alzheimer's Disease

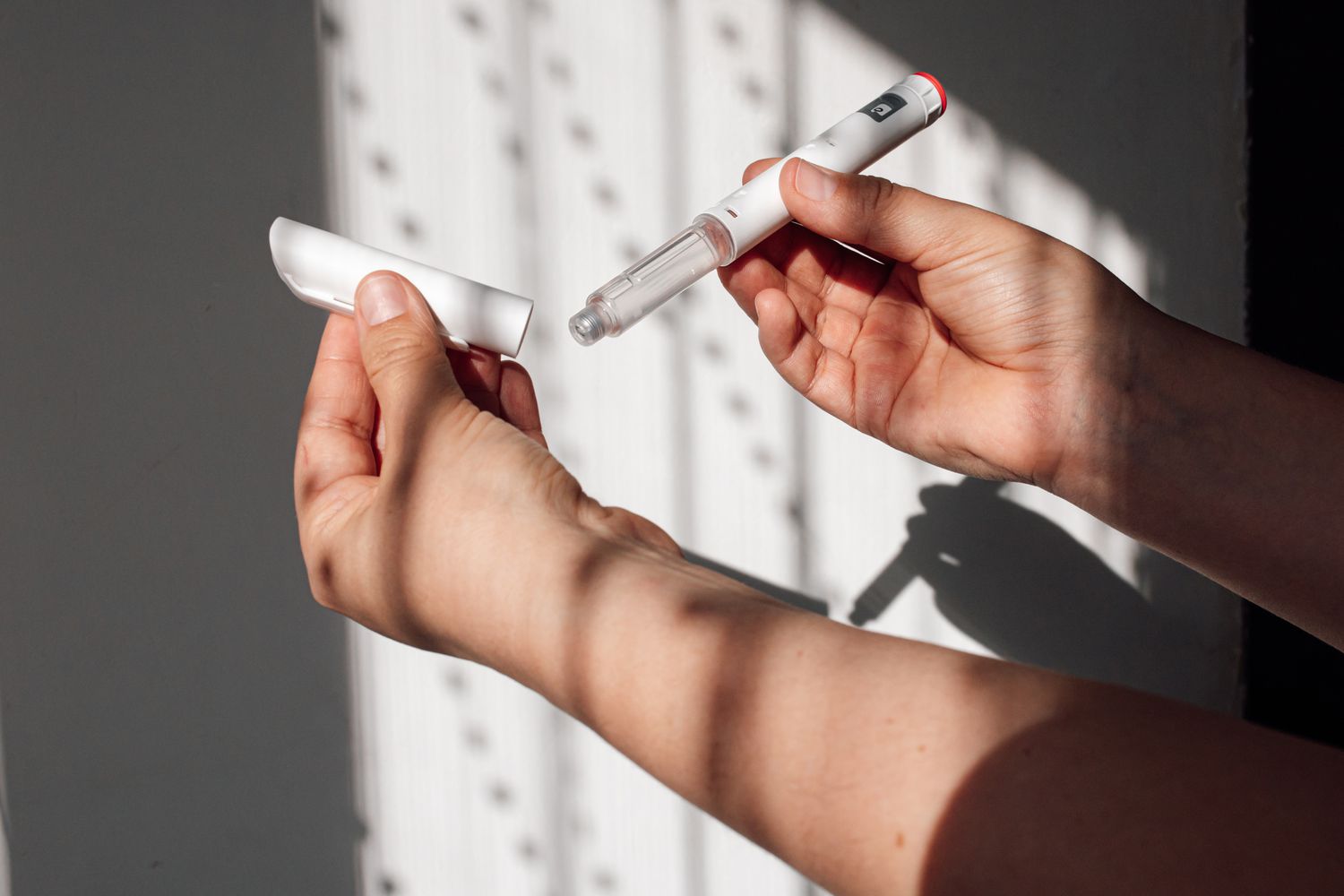

Semaglutide, sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, may reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s in people with type 2 diabetes, a new study found.

The research, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, raises questions about other potential uses of semaglutide outside of weight loss and type 2 diabetes management.

“I’m really excited about this study because if this drug can have a therapeutic effect, that could be very different from existing FDA-approved” approaches to Alzheimer’s care, Rong Xu, PhD, a professor of biomedical informatics and director of the Center for AI in Drug Discovery at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and author of the new study, told Health.

Experts stressed, however, that the findings in no way suggest that semaglutide can prevent or treat Alzheimer’s. “Studies [like] these kind of tell you that there is a possible signal that’s worth looking into more closely,” Jagan Pillai, MD, PhD, a neurologist at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, told Health. “This study does not add any light to how these medications are affecting the brain.”

About 6.9 million people aged 65 and older in the United States have Alzheimer’s, and that number is expected to jump to 13.8 million by 2060. There is no cure for Alzheimer’s, which is the most common form of dementia. However, some treatments, such as cholinesterase inhibitors and glutamate regulators, may help people manage symptoms of the illness.

Xu said her team conducted the study to learn more about the potential benefits of semaglutide, which is still relatively new: The FDA first approved its use for type 2 diabetes in 2017 (as Ozempic) and for weight management in 2021 (as Wegovy). Semaglutide has also been green-lit to lower the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke for some adults.

For the new study, Xu’s team analyzed data from the electronic health records of more than a million people with type 2 diabetes. Her team looked at how many people taking semaglutide were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease within a three-year period and compared that number to how many people taking other anti-diabetic medications were diagnosed.

Semaglutide belongs to a class of medications called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. The researchers also looked at the GLP-1 drugs albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, and lixisenatide, as well as other types of anti-diabetic medications:

Upon analysis, the team found that semaglutide use was associated with a 40% to 70% reduction in the risk of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis compared to the other medications studied. Those who took semaglutide were also significantly less likely to get prescription medications associated with Alzheimer’s disease filled.

There’s no solid answer as to why semaglutide may affect a person’s risk of Alzheimer’s. “There are a lot of hypotheses and theories, but so far, in humans, it has not been clearly shown why semaglutide is affecting Alzheimer’s,” Pillai said.

One theory is that semaglutide’s ability to manage diabetes helps it play a role in boosting brain health. “Diabetes is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s, and managing diabetes with drugs like semaglutide could benefit brain health simply by managing diabetes,” Courtney Kloske, PhD, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, told Health.

“Semaglutide is more potent for managing diabetes,” than other weight management drugs, Xu added.

Another hypothesis involves how semaglutide affects the brain: “Some research suggests that semaglutide may help reduce inflammation and positively impact brain energy use,” Kloske said. “[But] more research is needed to fully understand how these processes might contribute to preventing cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s.”

Xu said the question of how semaglutide might work to impact Alzheimer's risk needs to be explored in further research: “We need to figure out the underlying mechanism.”

While the results are promising, experts said it’s much too soon to know semaglutide’s actual effects on Alzheimer’s.

“This study also has a lot of caveats,” Pillai cautioned. “It’s not proven that these medications are effective” at reducing the risk of, or preventing, Alzheimer’s.

Kloske added that “large clinical trials in representative populations” are necessary to pinpoint if it’s semaglutide—or another factor—that might be lowering the risk of Alzheimer’s in people who take the drug. It may simply be that people who are on diabetes management drugs have access to better healthcare options than those who aren’t taking one of the other medications. High cholesterol, obesity and overweight, concussion or other brain injury, and mild cognitive impairment can also contribute to an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

It’s also unclear whether people who don’t have type 2 diabetes who take semaglutide would see a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s.

“The pressure is building to have a well-designed randomized clinical trial, [and] some of them are currently ongoing,” Pillai said. “Once those studies are completed, we’ll likely have an answer [as to whether this] is worth pursuing or not.”

Until more is known, experts said your best bet for protecting your brain as you age is following a healthy lifestyle. Strategies include maintaining a healthy weight, eating whole foods, getting enough sleep, not smoking, protecting your head, avoiding activities that might cause brain injury, and staying physically active.

“It is too early to recommend [semaglutide] for prevention,” Kloske said.