"Approved New COVID-19 Booster Shots: Optimal Timing for Your Next Dose"

As the summer surge of COVID-19 crests, many people are weighing whether they need to get booster shots now to protect against the disease (SN: 7/19/24).

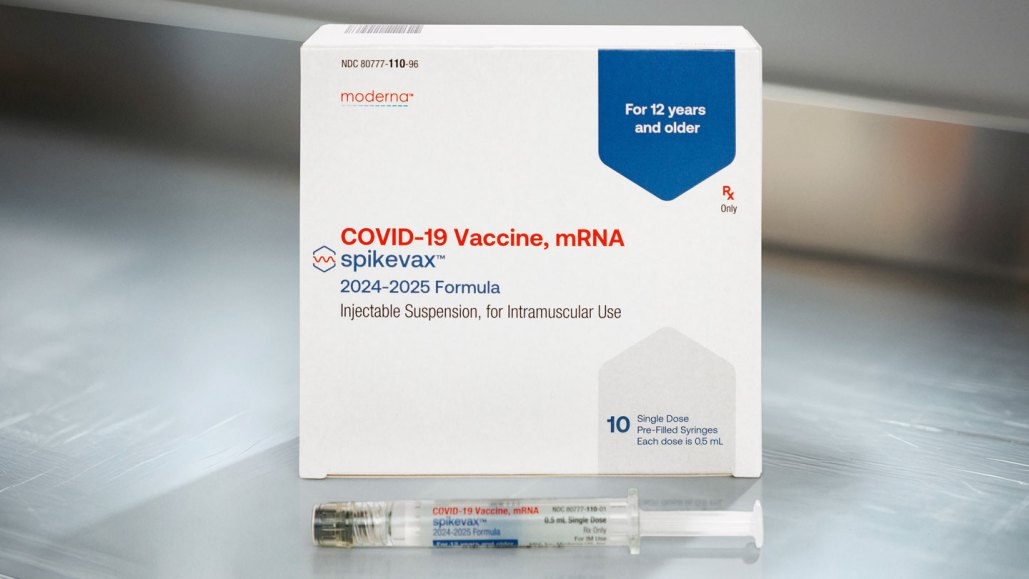

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved updated versions of mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna on August 22. The agency greenlit the shots for people 12 and older and gave emergency use authorization for children 6 months to 11 years old. Similar approval for Novavax’s latest version of its protein-based vaccine may soon follow.

Science News is collecting reader questions about how to navigate our planet's changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

Rollout of the new vaccines comes just before a program that temporarily paid for the shots for uninsured people expires at the end of August. That leaves about a week for people without insurance to decide whether to get a jab now at no cost.

“If this is your opportunity to get the vaccine, and after that, you aren’t sure if you’re going to be able to pay for it, I would absolutely get the vaccine now,” says Kawsar Talaat, an infectious diseases physician at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Here’s what else to know about the new shots.

They’re the exact same vaccine save for one difference, Talaat says — the viral strain that’s targeted. Last year’s jabs were aimed at the omicron XBB.1.5 variant that caused the majority of cases in late winter 2022 and spring 2023.

The new mRNA boosters target the omicron KP.2 variant (also called JN.1.11.1.2), which accounted for an estimated 3.2 percent of cases in the United States from August 4 to 17. Two other omicron variants, KP.3 and KP3.1.1, together make up nearly 54 percent of cases during the same period. Another variant known as LB.1 caused 14 percent of cases. And there is an alphabet soup of other variants circulating, too.

Novavax’s updated vaccine targets the JN.1 variant. That is the parent variant of KP.2, KP.3 and LB.1. The variants differ at only a few spots on their spike proteins, the knobby protein that the coronavirus uses to latch onto and enter cells. But the KP and LB.1 offspring may be a little bit more transmissible because those changes help the newer variants evade immunity from older versions of the vaccine and from infection with earlier coronavirus variants. It takes longer to reconfigure protein vaccines than it does for mRNA vaccines, so Novavax needed to go with the older version of the virus. In other countries, Moderna is making a JN.1 version of the vaccine, the company said in a statement.

This is the third time the vaccines have gotten updates to more closely match versions of the virus that are circulating. Each time the virus has been several steps ahead, but the shots have provided protection against severe disease, especially for older people and people with health conditions that put them at increased risk.

Infectious diseases physician Carlos del Rio says he’d like to see high vaccination rates in everybody over 65 years old because those people are at higher risk for hospitalization and severe disease. “Vaccination continues to be one of our major strategies in [managing] COVID,” says del Rio, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. “And keeping immunity up is important.”

Maximum protection against the virus lasts for several months after getting boosted, Talaat says. So “even if you get the vaccine now, you’re likely to have some protection at Thanksgiving and Christmas.”

People who were infected in this summer’s surge are probably still protected from repeat infections, she says, and can wait until the fall to get their updated shot. While it’s hard to predict exactly how long the current surge will last, test positivity rates and waste water levels of the virus are still rising (SN: 9/20/23). “COVID is still killing lots of people,” Talaat says. “We may not hear about it any longer, but it hasn’t gone away.”

Children returning to school could lead to a fresh round of infections. Just 14 percent of children ages 6 months to 17 years are up-to-date with the 2023–2024 COVID-19 booster, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And though more than 80 percent of adults 18 and over have received at least one shot, the number of people continuing to receive boosters has dropped steeply. Just 22 percent of people in this age group received a 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine dose, the CDC reported in data last updated in May.

Many scientists have investigated that question. One large study examining evidence of antibodies against the coronavirus found that by the fall of 2022 more than 96 percent of people in the United States had immunity from vaccination, prior infection or both.

But immunity can wane. For instance, last year, people who got the XBB.1.5 vaccine in Europe had pretty good protection against hospitalization from COVID-19 in the first month or so after getting the shot. The vaccines were about 69 percent effective 14 to 29 days after inoculation, researchers reported August 15 in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. Effectiveness dropped to 40 percent 60 to 105 days after vaccination. Part of the drop in effectiveness was because of the rise of the new JN.1 variants.

But protection doesn’t just fall off a cliff. New work offers evidence that the shots actually provide long-lasting benefits. Scientists performed an in-depth analysis of some 500 people’s immune responses over three years. Their results suggest that while the vaccine spurs an initial antibody boost that tends to fade rapidly, after a few months, antibody levels then stabilize, researchers reported in Immunity in March.

Updated versions of the vaccines may up that protection further. Pfizer submitted data to the FDA showing that its updated KP.2 version of the vaccine increased antibody production in mice and provided better protection against JN.1 and its offspring than last year’s version of the vaccine does.

One of the biggest misconceptions about these vaccines is that they prevent infection, del Rio says. A common refrain is: “Well, they don’t work because I still got COVID.” It’s true they’re not great at preventing infection, he says, but that doesn’t mean the vaccines aren’t working. “They’re very good at preventing severe disease and mortality.”

It’s still not clear if getting the vaccines will protect people from getting long COVID, del Rio says (SN: 7/17/24). Some data suggest yes, some suggest no. But, he says, “I think it’s a good idea to get vaccinated if you are worried.”

Talaat doesn’t see any real downsides to getting the latest booster. “All vaccines have some side effects,” she says. People may see the same types of symptoms they experienced with previous versions of the vaccine. Those can include sore arms, headache, joint pain and fatigue. She points out that billions of vaccine doses have made it into the arms of people worldwide. “They’re very safe,” she says.

Even if you’re young, healthy and at relatively low risk, Talaat still recommends getting boosted. “We need to do what we can to protect ourselves and our loved ones,” she says. Talaat plans to vaccinate her two teenagers “because their grandparents are in their 80s,” she says, “and I want to make sure that they stay safe as well.”

As for herself, Talaat says, “I’m seriously thinking about getting it next week.”

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at [email protected] | Reprints FAQ

FDA Approves and Authorizes Updated mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines to Better Protect Against Currently Circulating Variants. August 22, 2024.

K. Srivastava et al. SARS-CoV-2-infection- and vaccine-induced antibody responses are long lasting with an initial waning phase followed by a stabilization phase. Immunity. Vol. 57, March 12, 2024, p. P587-599. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.01.017.

I.R. Moustsen-Helms, et al. Relative vaccine protection, disease severity, and symptoms associated with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariant BA.2.86 and descendant JN.1 in Denmark: a nationwide observational study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. Vol. 24, September 2024, p. 964. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00220-2.

J. M. Jones, et al. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence and Incidence of Primary SARS-CoV-2 Infections Among Blood Donors, by COVID-19 Vaccination Status — United States, April 2021–September 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 72, June 2, 2023, p. 601.doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7222a3.

L. Antunes, et al. Early COVID-19 XBB.1.5 Vaccine Effectiveness Against Hospitalisation Among Adults Targeted for Vaccination, VEBIS Hospital Network, Europe, October 2023–January 2024.Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. Published online August 15, 2024. doi: 10.1111/irv.13360.

Tina Hesman Saey is the senior staff writer and reports on molecular biology. She has a Ph.D. in molecular genetics from Washington University in St. Louis and a master’s degree in science journalism from Boston University.

Meghan Rosen is a staff writer who reports on the life sciences for Science News. She earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology with an emphasis in biotechnology from the University of California, Davis, and later graduated from the science communication program at UC Santa Cruz.

We are at a critical time and supporting climate journalism is more important than ever. Science News and our parent organization, the Society for Science, need your help to strengthen environmental literacy and ensure that our response to climate change is informed by science.

Please subscribe to Science News and contribute $16 to help boost science literacy and understanding.