Study Reveals Many People Find Spiritual Practices Like Sermons and Silent Retreats Boring

March 6, 2025

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

by University of Vienna

We commonly consider spiritual practices as sources of peace and inspiration. A recent study led by researchers at the University of Vienna shows that they can also be experienced differently: Many people feel bored during these practices—and this can have far-reaching consequences. The results, recently published in the journal Communications Psychology, open up an entirely new field of research and provide fascinating insights into a phenomenon that has received only scant attention so far.

Even though boredom is a heavily researched subject at the moment, spiritual boredom has so far been largely neglected in research. Psychologists at the University of Vienna and the University of Essex have now decided to address this 'blind spot' and were surprised to find out that boredom frequently occurs during spiritual practice—and it can have a clear detrimental effect.

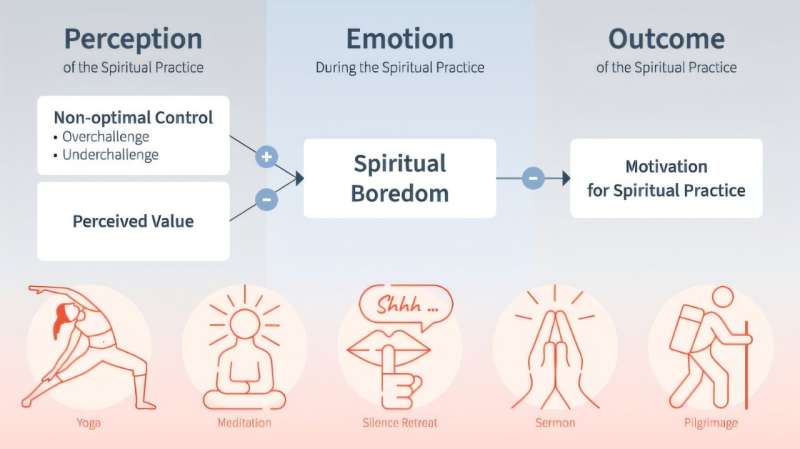

The control-value theory (CVT) provided the academic framework for the survey. The CVT posits that boredom—an unpleasant, aversive emotion characterized by changed time perception, wandering thoughts and the desire to escape the current situation—is primarily driven by two factors: perceived control of the ongoing activity and the subjective value we attach to it.

According to first author Thomas Götz from the Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology at the University of Vienna, 'Boredom develops when we feel over-challenged or under-challenged by an activity or task—a sign of an unsuitable level of control. And it also develops when we deem the value of the activity low.'

In a large-scale study analyzing five typical spiritual contexts (yoga, meditation, silent retreats, Catholic sermons and pilgrimages), the researchers studied more than 1,200 adults. The results show that the central triggers of spiritual boredom are in fact the feeling of being over-challenged or under-challenged as well as a lack of personal relevance for those practicing the spiritual activity.

Both have a negative effect on motivation and mindfulness during practice and may seriously dampen its positive effect. 'Our research shows that boredom in spiritual contexts can pose a serious obstacle, which reduces the transformative power of these practices,' says Götz.

In a world shaped by global crises, such as the climate crisis and social tensions, more and more people are hoping to find orientation through spiritual practice. However, the study shows that perceived boredom may inhibit this process.

'It is important to individually adapt spiritual practices and to repeatedly emphasize their relevance and meaning in order to promote their transformative value for our society,' says educational psychologist Götz. Based on the CVT, the research team recommends better personalizing spiritual practices and better responding to the needs of persons engaging in them.

'Spiritual teachers should maintain an active dialogue with those involved in the spiritual practice about feeling over-challenged or under-challenged. In addition, they should emphasize the relevance of spiritual practice for a fulfilling life,' explains Götz. These measures could contribute to reducing spiritual boredom and to maximizing the positive effects of spiritual practice.

This first study on spiritual boredom has opened up a completely new field of research. The research team has made an important contribution to demonstrating the negative effects of boredom during spiritual practice.

More information: Thomas Goetz et al, Spiritual boredom is associated with over- and underchallenge, lack of value, and reduced motivation, Communications Psychology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-025-00216-7

Journal information: Communications Psychology

Provided by University of Vienna