A Young Emerging Painter Shines at Art Basel Miami Beach | Vanity Fair

You can go to Art Basel Miami to buy something expensive made by someone famous—or you can go to Miami to discover something new. Since the fair arrived in 2002, a number of artists have seen their stratospheric rise start in the Magic City, then have taken that momentum to New York, LA, or Europe. I’m thinking about how at the first Art Basel Miami Beach, a young Mark Bradford set up a pop-up of his mother’s hair salon in the Lombard Freid Fine Arts booth, and only charged for tips—in 2022, Hauser & Wirth sold a Bradford painting for $2.5 million. I’m thinking about how, in 2014, Alma Allen was showing works at the NADA fair at the Deauville—and now he’s representing the US at the Venice Biennale. I’m thinking about how, at NADA in 2015, Henry Taylor was selling works out of Fontainebleau’s lobby for $55,000—and now 10 years later, Hauser & Wirth is selling a Taylor painting for $1.2 million.

But the most prominent and vigorous backers of young artists in Miami have to be Don and Mera Rubell, who opened the Rubell Family Collection in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood in 1993—it was, at the time, the pioneering example of the now ubiquitous model of a collector-led private museum.

Going back to their days in New York, the Rubells were early supporters of emerging artists. They were the first to throw their weight behind Richard Prince, Rashid Johnson, Jeff Koons, Rosemarie Trockel, and George Condo. But it’s when they initiated a residency program for young artists in Miami that would give them space to make work in the tropics—along with a platform to show it off during the aforementioned Miami Beach bash—that the stars really started to align. First up at the residency was Sterling Ruby, now a superstar. This is how Oscar Murillo initially got the exposure that led to shows with David Zwirner in New York. Amoako Boafo stunned Miami in 2019 with his Schiele-gone-Ghana color-popped paintings—he was making them in complete obscurity in Austria, but once he brought them to the Rubells, he became famous overnight. Eventually, the Rubells expanded the program to feature not only the artist-in-residence, but also artists new to the Rubell collection.

And it’s where Lorenzo Amos, a painter with an unending buzz humming around him in downtown New York, is making his first big splash outside of Manhattan, with a room full of new paintings that are among the most-talked-about artworks in all of Miami during Basel. It’s his last show of 2025, before a 2026 itinerary that will take his work to some major galleries and institutions in Europe.

I’ve known about Amos for a few years, at least since his solo show with the Gratin Gallery in 2024. The opening was memorable—the show was an entire downtown demimonde that he had conjured up in his small one-bedroom. He then turned the Gratin’s East Village gallery into his studio and finished the show there, complete with paint spillage on the floor. He’d created an entire world on the canvases, a very distinct chronicling of his friends and their partners. That evening, hundreds of skaters and scene kids spilled out onto Avenue B. Everyone was incredibly young, like Amos—that’s the first thing that I’ll say about Lorenzo: It’s striking how young he is. He’s just 23.

“Everyone was shocked because everyone knew Lorenzo, but they didn’t know that he could do that in such a poetic, strong romantic way,” said Talal Abillama, the energetic and omnipresent young art dealer who started Gratin in 2023.

Amos will never not be a ringleader of the downtown scene, beloved by his fellow artists and muses. The buzz was so deafening that the institutional cognoscenti came in droves, and Abillama sold work from that first show to Vancouver mega-collector Bob Rennie and Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, who has a private museum in Turin. But the show’s foot traffic was consistently kids outside the art world drawn into the work purely by sight.

“And there’s something in this: There’s so many people coming to me and telling me—they don’t even buy art, but they’re telling me, ‘Oh, I want to buy a painting,’” Abillama said. “And then people who were also very sophisticated were asking me about the work as well. So this wide range of people asking me about the work—it means something because it just really talks to everyone.”

Abillama has built one of the most exciting post-pandemic art galleries in downtown Manhattan through artists like Amos—young painters who are fiercely ambitious and naturally sociable and deeply cosmopolitan. Amos is the only American-born artist on the roster, though he spent part of his childhood in Milan. He’s completely self-taught. In 2023, the artist Calvin Marcus told Abillama to check out Amos, who was then showing some work with Paul Henkel, the third-generation collector who founded Palo on Bond Street and has the only gallery below 14th designed by the go-to architect for the mega-gallerists, Annabelle Selldorf.

Then Abillama started seeing Amos everywhere—in the club in Brooklyn, on the streets of Alphabet City. The dealer went up to the makeshift studio in the young artist’s rent-controlled pad, loved what he saw, and asked Amos to make two big paintings. Abillama put the paintings in the back room of a group show he staged during Frieze LA in 2024, and collectors could not stop asking about them. They didn’t know the artist, and they certainly didn’t know that he was 21 years old.

I saw Amos again in mid-November, at a dinner Abillama threw with Fair Warning’s Löic Gouzer, at the art world‘s great canteen, Lucien. At the bar, we talked about doing a studio visit—the works were already shipped to Miami, but he was cooking up some new stuff.

A few weeks later, I arrived at a stretch of Bushwick—the musk of the fetid Newtown Creek in the air—where the only people you see are sheet-metal workers, or artists who work at the cheap studios in converted industrial spaces. From blocks away, I saw Amos sitting on his stoop but didn’t recognize him at first, as he had cut his hair into a mohawk. It was my first studio visit with an artist who was born after 9/11.

We sat on the couch, a Clash record on the speakers—Sandinista!. Amos opened a bottle of beer, and I asked how the Rubell show came about. He had a show at Market Gallery, the 200-foot space in a former shed on top of a building in Chinatown—it’s run by Supreme’s Adam Zhu, and it’s kind of a thing.

“I was working on the show at Market, and Talal was like, ‘Oh, the Rubells want to buy something,’” he said. “But I didn’t really understand what it was, I just wasn’t thinking about it. And then in June, Talal told me, he was like, ‘Oh, they want to do a room. You have to paint some big paintings.’”

But it wasn’t for the Rubells’ museum in Washington, or for Miami in summertime—it would open the day before the start of Art Basel Miami Beach.

“Yeah, I started the paintings, but I didn’t really even believe that I was going to do this thing until they announced my name on it,” Amos told me.

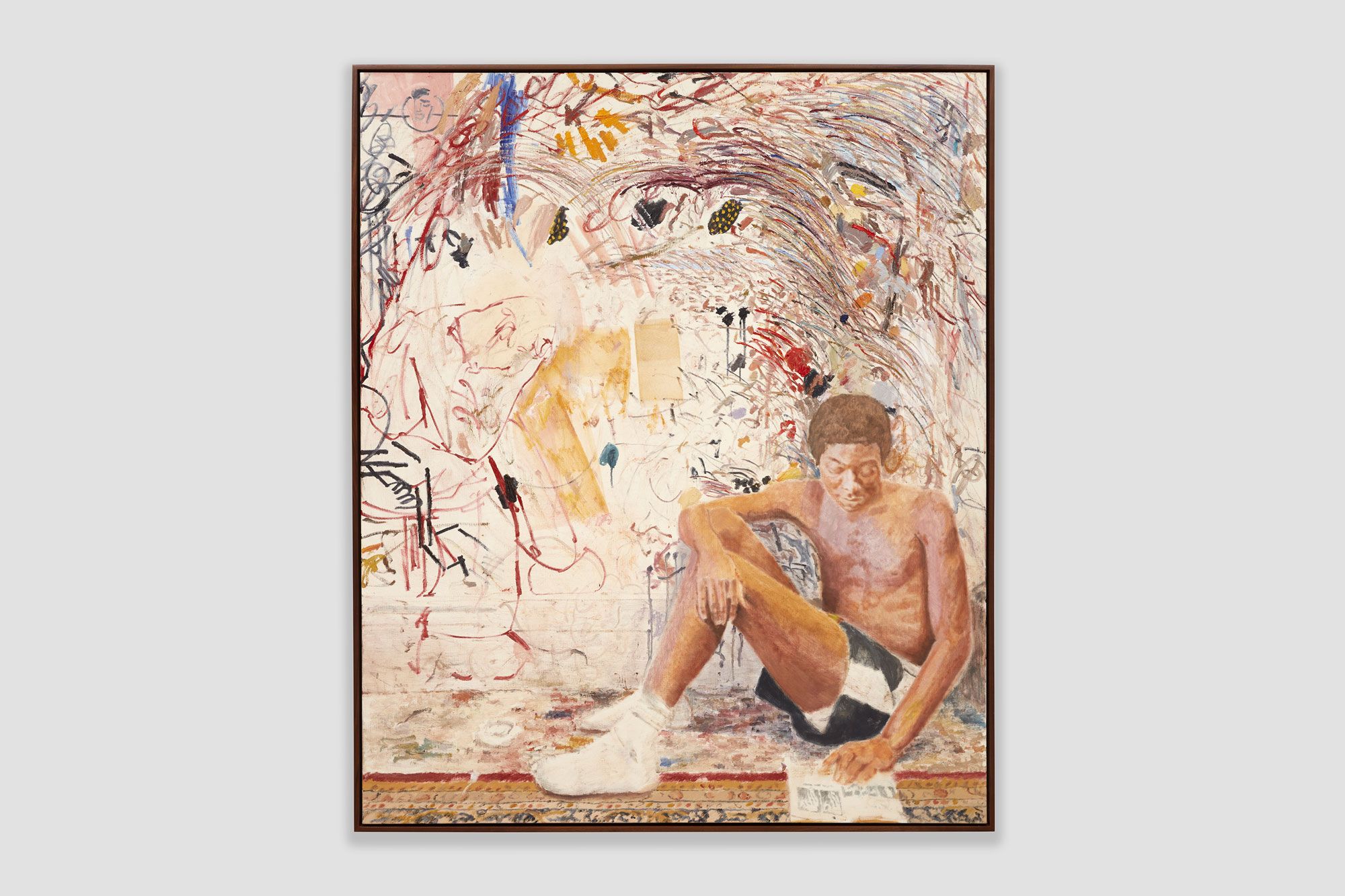

He used to work out of his apartment in the East Village, in a Beaux-Arts 1899 building between Avenues A and B, rather than a real studio. The intimacy that comes with making art in a domestic space—of mingling the quotidian habits with the otherworldly process of creating—carries over to the space in Bushwick, infusing everything he makes. He started painting friends in his apartment, and to save space, he used the walls as a palette and a place to clean his brushes. After dozens of sittings, the paint had started to accumulate all over the walls, and he thought all that paint could work as the subject of a painting itself. He started taking pictures of his friends in front of where he made the old paintings, and made paintings from those photographs.

Thus, he suffuses each new canvas with what appears to be abstracted color fields, but they are based on marks that really exist in the studio. At least they did at that moment—he’s recreating the remnants of past paintings from his studio walls, recording the progression of time, preserving in amber certain periods there.

“I think it started looking at Lucian Freud’s paintings, and some of the paintings have marks of paint in the background because he would paint people in his home,” he told me. “And I was upset at a lot of abstract art, and I felt it was lazy, and I felt like it was just not useful—I would go to MoMA, and I wouldn’t like anything, and I’d go to The Met, and I’d like everything.”

He wanted to depict something that was actually there, but abstracted from reality. What he was looking for, it turned out, was staring at him when he looked at the walls of his studio.

“My way of getting back at the abstract art was making realistic abstract art,” he said. “It’s obviously these abstract paintings, but so much more realistic than paintings of people, because I’m representing paint with paint.”

Oftentimes, the studio becomes a messy mood board, with things taped or tacked up to provide either direct or indirect inspiration. There’s a photograph of himself that I’ll later see, in painted form, in the middle of a painting at the Rubell.

“That’s me as a kid, painting,” he said. “Everybody’s always like, ‘When did you start painting?’ And so I always keep that photo up.”

The studio is going to get pretty full in the next few months. He’s got a few works in a group show at Max Hetzler in Berlin that’s filled with heavy hitters, and he’s making work for a private museum in the same city that will be up for years. Abillama is opening a permanent outpost of Gratin in Paris next year—“Everyone wants to spend money in Paris,” he said, by way of explanation—and Amos will have a show there. Certainly, there are bigger stages to come.

“He puts so much pressure on himself—he’s never satisfied, never, and I think that’s a great sign of a great artist,” Abillama said. “He’s never complete. It is just like, ‘No, I got to do more. No, there’s something wrong.’ And I’m looking at it like: That’s like the greatest thing I ever saw! He is like, ‘No, it’s not.’”

And Miami was a huge hit—thousands filtered through the room at the Rubell Museum, and afterward, Abillama had a late dinner party at a house that Dwyane Wade sold in 2021 for $22 million. It was an appropriately lavish celebration, with prominent European dealers chowing down on steak, staring out at the Biscayne Bay, and waiting to see what happens to Amos next.

“A lot of people are telling me, ‘This is going to happen, that’s going to happen,’ and stuff is happening all the time—I’m 23, so for this stuff to be happening is a lot,” he said. “I don’t even know, honestly, what to do or how to prepare. I guess all you can do is keep people around you that protect you and make you feel safe.”

Have a tip? Drop me a line at [email protected]. And make sure you subscribe to True Colors to receive Nate Freeman’s art-world dispatch in your inbox every week.

The 13 Biggest Snubs and Surprises From the Golden Globes Nominations 2026

As Netflix Swallows Warner Bros., Hollywood Is in Full-Blown Panic Mode

Meet the 11 Best Movies of 2025

Even Christians Have Had Enough of Ballerina Farm

Versace’s Rollercoaster Year, Explained

The 19 Best TV Shows of 2025

How Melania Trump Is Bringing the Christmas Spirit to the White House

Unpacking the “Atom Bomb” of the Oscar Wilde Scandal

The 2026 Hollywood Issue: Let’s Hear It For the Boys!

From the Archive: Behind the Mysteries of Capote’s Swans Scandal