How This Year’s Climate Conditions Fueled Hurricane Beryl’s Record-Breaking Fury

Hurricane Beryl, the Atlantic Ocean’s first hurricane in 2024, began roaring across the Caribbean in late June, wreaking devastation on Grenada and other Windward Islands as it grew in power. It’s now swirling on like a buzzsaw toward Jamaica and Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula.

Beryl is a record-breaking storm, commanding attention in a year already filled with record-breaking climate events (SN: 6/21/24; SN: 4/30/24).

On June 30, the storm became the earliest Atlantic hurricane on record to achieve Category 4 status. Just a day later, it had intensified further, becoming the earliest Atlantic storm on record to achieve Category 5 status, with sustained winds of about 270 kilometers per hour, according to the U.S. National Hurricane Center in Miami. (As of late July 2, the storm has weakened slightly but remains a powerful Category 4 ahead of making landfall in Jamaica.)

Fueling Beryl’s fury are the superheated waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Numerous teams of scientists have predicted that 2024’s Atlantic hurricane season would be “hyperactive” as a result of that record-breaking ocean heat, as well as the pending onset of the La Niña phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, climate pattern (SN: 4/29/24).

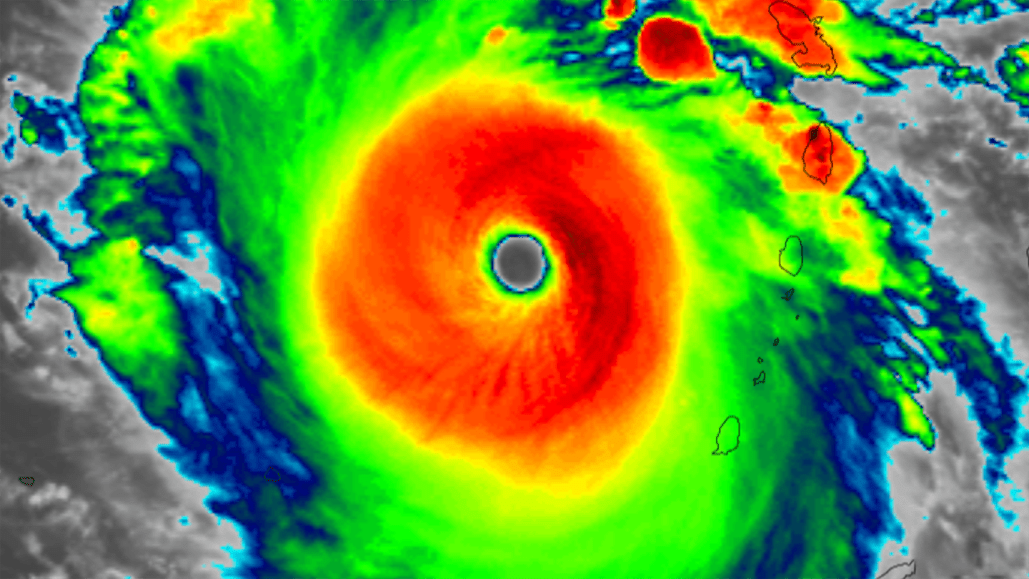

Predicted or not, scientists are still agog at the stunning satellite images of Beryl, and the swiftness with which the storm gained power, says Brian McNoldy, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Miami. Science News talked with McNoldy about hurricanes, ocean heat and what to expect for the rest of the Atlantic season. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SN: I’m looking at these satellite images, and this ocean temperature data, and I’m stunned.

McNoldy: Anybody who’s been looking at this stuff is amazed. It’s just off the charts, to be at the end of June-early July, and the ocean has more heat content than it would at the peak of the hurricane season! And we’re far from the peak.

SN: So let’s talk ocean heat. We knew, even last year, that 2024 was likely to break records. What are we seeing now?

McNoldy: This year, the whole tropical Atlantic has been warmer than average, both in terms of sea surface temperatures and ocean heat content. In terms of ocean heat content — if we’re just zooming in on the Caribbean, which is the relevant part for this hurricane — it is easily at a record. The ocean heat content now looks more like it normally would the second week of September, [at the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season].

The swath of the North Atlantic Ocean where most of its hurricanes form, known as the “main development region” (see inset map), was primed with superhot waters to fuel powerful storms even before Hurricane Beryl began to organize. The region’s ocean heat content — a measure not just of temperature at the ocean’s surface but extending deeper into the water column — has been higher than ever measured before in 2024 (dark red line), even surpassing 2023 (lighter red line), which was the previous record holder. The average ocean heat content for the main development region from 2013 to 2023 is shown in blue.

SN: What’s the difference between sea surface temperature and ocean heat content?

McNoldy: Sea surface temperature is nice and self-explanatory — it’s just the temperature right at the surface of the ocean. Ocean heat content is a measurement of how deep that warm water goes. It can be measured in a few different ways. The data I’m processing [to analyze ocean heat trends] calculates ocean heat content based on temperatures that are 26° Celsius or higher. That’s a very tropical cyclone-oriented number — generally we think of hurricanes being able to form and maintain themselves [with water temperatures at] 26° C or higher. If water that warm is just skin-deep, the ocean heat content is very, very small. But if that warm water goes a lot deeper, the ocean heat content is large.

SN: Why does ocean heat content matter for hurricanes?

McNoldy: For storms like Beryl, very strong storms, if it were moving over a part of the ocean where the warm water was skin deep, it would easily churn up cooler water to the surface, [which can reduce its intensity]. It’ll also leave a cooler wake behind it. But in this case, I kind of doubt we’re going to see much of a cold wake, because the warm water is so deep, it’s just going to churn up more warm water. The hot waters goes down to probably about 100 to 125 meters deep. So it’s not going anywhere. Storms don’t even churn up water that deep. It’s pretty crazy.