The Potential Diminished Efficacy of a Well-Known Breast Cancer Drug among Certain African Populations

WASHINGTON — A prevalent genetic variant in certain Africans populations may counteract the influence of a popular breast cancer medication.

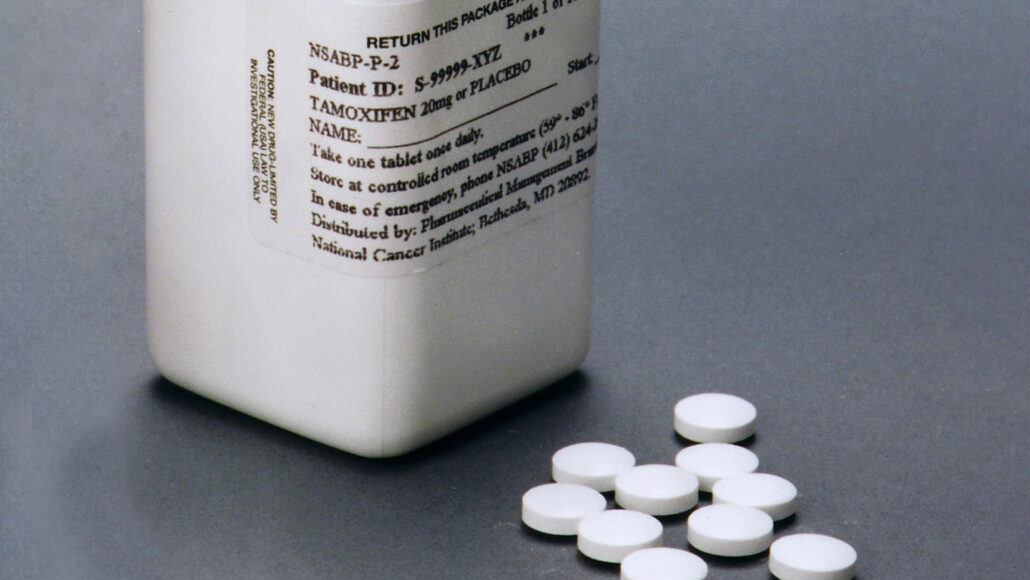

This variant results in a slower form of the enzyme responsible for activating tamoxifen. Those born with dual copies of the variant have five times less of the active drug in their blood compared to those without the variant, according to researchers at the American Society of Human Genetics' annual meeting on November 2. Consequently, these patients might receive a dose that is ineffective in treating their cancer.

The variation of the gene named CYP2D6, which generates the critical enzyme, is significant among individuals. Approximately a fifth of the African population carry one copy of the variant that the researchers explored. That figure, however, ranges from a slight 5 percent to over 34 percent across the continent.

Molecular geneticist Comfort Kanji, stationed at the African Institute of Biomedical Science and Technology in Harare, Zimbabwe, believes preemptive genetic screening that reveals patients with the genetic variant would likely be financially burdensome for local clinics and hospitals. However, he envisions that his team's discovery could lead to clinical trials examining larger initial dosages of tamoxifen in heavily impacted groups.

Kanji and his team gathered daily blood samples from 42 Zimbabweans on tamoxifen. Some had one copy of the variant, some had two, and others had a different variant of the gene that did not affect the enzyme. Differences in their metabolization of the medication were observed immediately and lasted throughout the month-long study.

The researchers found that doubling the dose for those with two copies of the variant normalized levels of the active drug in the blood, with minor short-term effects.

David Twesigomwe, a pharmacogeneticist at the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience in Johannesburg, not connected to the research, suggests the study offers a strong case for metabolic screening, despite a small sample size. While broad genetic testing remains inaccessible for many Africans, he posits that more specific, narrower tests could be effective, potentially establishing a basis for more widespread screening in treatment.

Approximately 200,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa receive breast cancer diagnoses annually. Less than 40 percent survive beyond five years after diagnosis, compared to an 86 percent survival rate in the United States. This discrepancy mainly stems from difficulties in African patients securing or affording treatment, consequently presenting at clinics with advanced-stage cancers. While this recent discovery is not likely to change this situation drastically, it could contribute to making early care more impactful, says Kanji.

Worldwide, around 30 percent of patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer — the most common type — show minimal improvement on tamoxifen. This figure is even higher in African females, Kanji adds. The high prevalence of the analyzed gene variant, or others with similar effects, may partially explain this higher percentage.

Kanji and Twesigomwe agree that a different study would be necessary to determine if these findings apply to African Americans. In the US, Black women have a 40 percent higher risk of breast cancer mortality, even though the diagnosis rate is similar among Black and white women.

Experts warn the causes of this disparity are complex, including biological, sociological, and historical factors. The role that a variant of CYP2D6 plays may provide a small piece of the puzzle.

The gene-generated enzyme affects more than just tamoxifen. It metabolizes numerous other medications, including opioids, beta-blockers, and a widely used category of antidepressant drugs named selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Therefore, those with various variants of the gene may have better or worse reactions to these drugs as well.