The Long-Unsolved Mystery of a 19th Century Dinosaur Whodunit Unveils Its True Culprit

The last hope for a palaeontology museum in New York City was crushed by a sledgehammer.

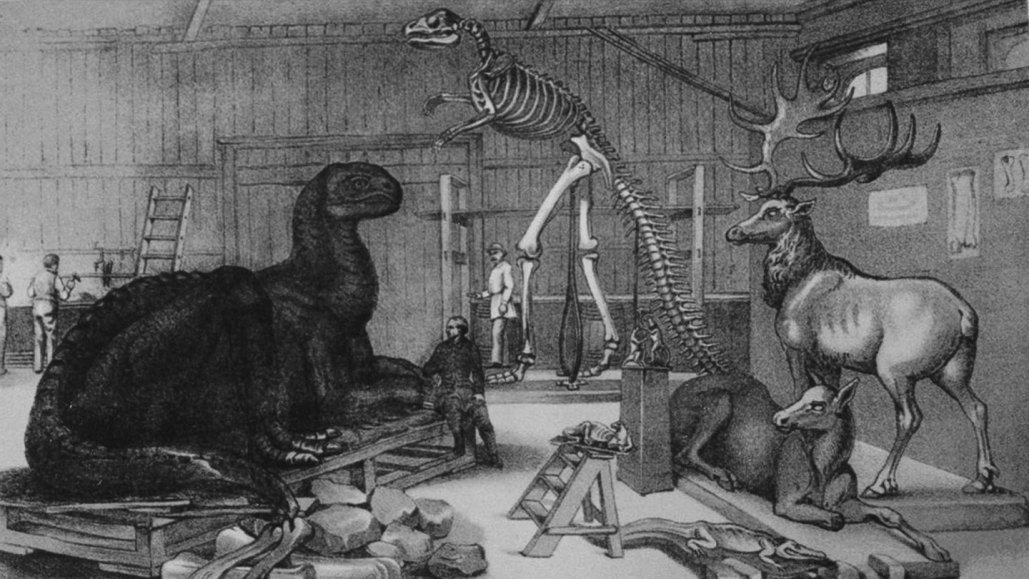

Workers infiltrated the studio of renowned British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins on May 3, 1871. They discovered a plaster skeleton of a towering duck-billed dinosaur – a model based on the first dinosaur fossil found in New Jersey 13 years prior – next to a sculpture of the creature in its living state.

These constituted the inaugural 3-D representations of any North American dinosaur, representing an epoch of geological history that was only starting to be grasped by scientists. However, neither the skeleton nor the sculpture were ever seen by the general public.

The studio was devastated by the workers. The dinosaur models were obliterated by sledgehammers, and drawings and plans were ripped apart.

This act of vandalism which occurred over 150 years ago, remains one of the most notorious incidents in the history of palaeontology. It’s widely believed that the destruction was instigated by New York's political boss, William Tweed, as an act of spiteful political and religious retaliation.

A palaeontologist noted in 1940 that Tweed was opposed to dinosaurs because they contradicted the tenets of conventional religion. This is commonly cited as an early conflict between the traditional Christian perspective and emerging scientific knowledge of Earth's distant past.

The destruction of Hawkins’ dinosaur models has consistently astonished the paleontological world, explains Vicky Coules, an art historian at the University of Bristol, England. The belief is that Tweed found the very notion of dinosaurs objectionable.

However, new historical investigations by Coules and her Ph.D. supervisor Michael Benton, a paleontologist also from the University of Bristol, indicate that the destruction of Hawkins’ dinosaur models was not religiously inspired or commanded by Tweed.

Rather, the narrative presented by paleontologists about this event, may be more of a reflection of anti-evolution sentiment in the 20th century, rather than the 19th century.

Currently, dinosaurs have an omnipresence, symbolizing the prehistoric age. Their placement in the public consciousness can be significantly attributed to Hawkins.

Throughout his career, Hawkins endeavored to visually represent the natural world, even assisting Charles Darwin in illustrating the 1839 book The Voyage of the Beagle. In 1854, Hawkins’ most renowned artwork was exhibited when the Crystal Palace in London was reopened. A natural history section of this exposition of treasures from across the British Empire, included life-size dinosaur models created by Hawkins.

This took place several years before Darwin propounded his theory of evolution and approximately a decade after the word “dinosaur” was first introduced. For many, witnessing Hawkins’ models was their initial encounter with the concept of deep time.

Showcasing life-size dinosaur models was pioneering, according to Benton. No one had attempted such a feat before.

This display established Hawkins as the go-to expert on portraying prehistoric life, and in 1868, the Central Park’s Board of Commissioners tasked him with creating similar sculptures. These were intended to be the feature attraction of the park’s proposed Paleozoic Museum, to be dedicated to American palaeontology.

Most significant dinosaur discoveries at the time were occurring in Europe or their colonies. Palaeontologists in America were yet to explore the abundant fossil deposits in the country’s west, and many of the significant palaeontological finds of the continent – including Tyrannosaurus rex – were still at least a decade away.

However, a few fossils were being discovered on the East Coast, including a flat-snouted dinosaur discovered in New Jersey named Hadrosaurus. The Paleozoic Museum, the Central Park commission believed, would give Americans the opportunity to show that their country too had a noteworthy prehistoric past. According to Benton, Hawkins’ Crystal Palace statues made a big impact on the public, and New York wanted the same.

Embracing this challenge, Hawkins dedicated several years to a museum that would never see its grand opening.

In the 1860s, New York was a rapidly progressing city. Among those benefiting from this prosperity was William Tweed, a state senator who controlled the city's political arena. Tweed dismantled the power of anyone who stood against him. In May 1870, he terminated the Central Park’s board of commissioners and established a new group filled with his supporters.

By the end of the year, the fresh batch of commissioners scrapped the Paleozoic Museum and sought to terminate their contract with Hawkins, without providing him with any compensation.

For several months, the downfall of the museum had been brewing. Hawkins' workshop was shifted from a government building to a park shed, paving the way for the American Museum of Natural History's growing collection. Unlike the public-funded Paleozoic Museum, the American Museum had the private financial support of New York's richest individuals, including banker J.P. Morgan.

Both museum plans were considered together for some time. However, park commissioners concluded that a public-backed museum focusing exclusively on paleontology was an overwhelming commitment. A serious issue was that a member of the park commission was also a committee member for the American Museum of Natural History.

In March 1871, the New York Times, which often published stories against Tweed, highlighted the termination of the Paleozoic Museum. Hawkins had expressed his dissatisfaction at a public gathering.

Just two months later, the artist's dinosaur models were reduced to fragments.

"Hawkins was devastated," Coules states. This disaster echoed throughout the scientific community and eventually became a cornerstone tale in American paleontology history, according to her.

Tweed was identified as the story's culprit.

A Times report apparently infuriated Tweed, and he instructed his crony to unleash his wrath on the Paleozoic Museum, say later generations of paleontologists.

Tweed wasn't only upset by the negative publicity. Paleontologist Carl Mehling of the American Museum of Natural History claims, "Rumor has it there was some sort of creationist perspective to it."

This narrative, recited by paleontologists since the 1940s at least, revolves around Tweed and his men referring to Hawkins’ dinosaurs as “pre-Adamite” animals and a moment when one of Tweed’s followers suggested Hawkins concentrate on living animals. This suggestion falls into the widespread belief that emerged during the mid-20th century that religion and prehistory were frequently in conflict in the late 19th century.

Here begins the disentanglement of the Central Park story.

Last year, while Coules was working on her Ph.D., she delved deeper into Hawkins' tale and found inconsistencies.

Firstly, the sequence of events was odd. Why would Tweed respond to the Times article two months late? Also, the article was buried on Page 5, with no reference to Tweed.

"I wondered, why on earth would you be upset about that?" recalls Coules.

Tweed had bigger issues to address at the time, such as accusations of bribery and money laundering. (He was eventually apprehended later in 1871 and died years later in jail.)

Coules started to consider an alternate target: Henry Hilton, a prominent lawyer representing New York's wealthy, appointed by Tweed to head the new board responsible for Central Park in 1870. Hilton committed himself to the role, often visiting the park to identify potential enhancements.

Some of Hilton's upgrades were strange, like having a biblical bronze statue of Eve painted entirely white, irrevocably damaging the metal. Hilton's preference for destructive whitewashing became a press joke.

While reviewing her notes, Coules stumbled upon park commission records the day before the models were ruined. The committee agreed to dismantle Hawkins’ workshop "under the direction of the Treasurer" — Henry Hilton.

"I was thrilled. Look at this!" says Coules. Hawkins himself held Hilton responsible for the vandalism. Coules discovered articles in the New York Times from that era where Hawkins accused Hilton.

Why did Hilton want the dinosaurs destroyed? Coules' investigation didn't suggest that religion was a significant driver. Instead, she believes, Hilton "had a peculiar relationship with artifacts," reflecting in his whitewashing tendencies.

Hilton also displayed other destructive behaviors – deceiving a rich widow out of her wealth and driving her deceased husband's company to ruin.

Coules, who shared her discoveries last year alongside Benton in the Proceedings of the Geologist’s Association, comments, "Hilton had rather unusual ideas [that managed] basically to aggravate everyone."

That Hilton’s “strange ideas” would be behind the Hawkins incident makes sense to Ellinor Mitchel, an evolutionary biologist at the Natural History Museum in London and coauthor of a book on Hawkins’ Crystal Palace dinosaurs. “I think that’s the way of much of history, that it turns it’s sort of out human strengths and weaknesses that pivot the direction of things,” she says.

But not everyone is so sure. “It seemed quite convincing to me that Hilton played an important role,” says Lukas Rieppel, a science historian at Brown University in Providence, R.I., and author of a book on dinosaurs during America’s Gilded Age. But “it’s very hard for historians to know the private motivations of people who died over 100 years ago.”

Still, Coules’ work convincingly shows religion wasn’t a motivating factor.

For one thing, “pre-Adamite” was simply a way to refer to deep time, Benton says. So even if Tweed and Hilton did refer to Hawkins’ models in this way, it would have been more descriptive than derisive. What’s more, natural history — including paleontology — was seen as a respectable, middle-class occupation in the 19th century. “Natural history was seen as an expression of piety,” Rieppel says. “So a way that one could express one’s devotion to God [was] by learning about God’s works in the natural world.”

In fact, the idea that the world was ancient was widely accepted at the time, Benton adds. A more inflexible view of creationism, in which evolution is false and the world is only a few thousand years old, really started to gain steam only in the 20th century, he says.

Religion’s supposed role in the Hawkins’ saga may have been introduced by paleontologists writing about this incident in the mid-20th century, who may have been projecting their experiences with creationist movements into the past, Rieppel says. From there, the story stuck.

The loss of the Paleozoic Museum might have been for the best. It would have been “obsolete almost immediately and I fear almost comical,” Mehling says — soon overshadowed by bigger discoveries from the American West.

But that doesn’t mean that Hawkins’ models didn’t have value, Mehling says. Dinosaur statues may now be the stuff of tacky roadside attractions and miniature golf courses. But in the 19th century, Hawkins’ statues were key to opening the public’s imagination to an ancient world that was quite different from the present.

Hawkins’ display was so awe-inspiring that in 1905, when the American Museum of Natural History unveiled its 20-meter-long Brontosaurus, it displayed the skeleton upright (SN: 4/7/15).

And Hawkins’ work continues to influence how people think of dinosaurs. While doing research for the Paleozoic Museum, Hawkins strung together the fossil pieces of Hadrosaurus into a standing skeleton and displayed it in Philadelphia. Before this, fossils had only ever been displayed flat on a table or kept in drawers. Visitors flocked to see the strung-together skeleton, overwhelming staff at the institution where it was housed.

The tradition stuck. And today, most museums display their fossils using Hawkins’ method.