The Impact of Matthew Perry's Book on Remembering His Desire to Help Others

Article Written by Hillary Busis

Despite being an ardent fan of Friends, I can't wholeheartedly endorse the much-anticipated Friends reunion that aired on HBO Max in 2021. Owing to the fact that the stars and creators of the show didn't want a fully scripted reboot, the 104-minute special is primarily a recapitulation of behind-the-scenes stories, with a few ingenious interludes.

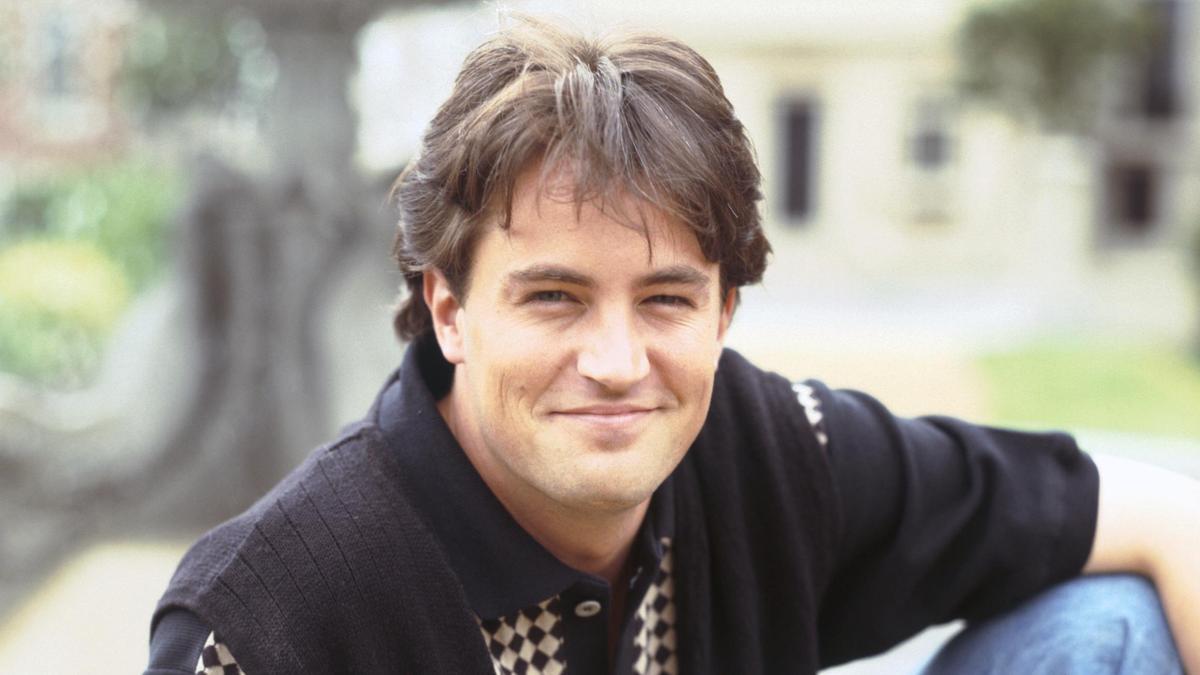

However, the reunion features one segment that I’ve found myself mulling over for the past couple of years. It occurs when Matthew Perry—who depicted Chandler Bing, the group's biggest joker—uncovers the immense anxiety he experienced even as Friends became a sensational, transformative hit. Perry admits, in front of Friends’ live studio audience, that he would fear he would die if they did not laugh at his jokes, causing immense stress every time he stepped in front of the audience.

Post Perry's disclosure, the special switches the topic quickly. It would have been more impactful if it had discussed what Perry said, especially as it is the only time Friends: The Reunion even indirectly acknowledges Perry's precarious mental health, let alone his struggles with alcoholism and drug addiction.

Perry passed away at the age of 54. Although it is still unknown what caused his demise, it is reported that he was found unresponsive in a hot tub, with no illicit drugs located at the scene. Despite the internal agony he was enduring, Perry was an accomplished actor, concealing his pain behind his every performance.

Particularly in the initial seasons, Perry's character Chandler was portrayed as a nervous wreck. Despite this, Perry never really showed any signs of pressure. He was the epitome of a natural comedic actor, making his performances seem seamless.

Although Perry confessed to not being able to recall filming entire seasons of Friends, his harrowing life struggles revolve around his numerous rehab stays, detox sessions, and surgeries on his body damaged by opioid misuse. His struggles remained unnoticed for several years, while he appeared to carry out his job effortlessly.

I, like other older millennials, have watched Friends multiple times. The show accompanied me through my younger years, the series finale coordinated with my sister, Anni's high school graduation. Despite my love for Friends, Anni held regular dialogues using Phoebe Buffay quotes. Her dedication to the series even drove her to furnish her college dorm room in homage to Joey and Chandler.

My sister and Chandler shared a knack for one-liners, and just like Matthew Perry, she mastered the art of concealing her drug addiction, until it was too late. I've attempted to understand the opioid crisis and the loss of my sister through countless books and films since her fatal overdose. From Dopesick to Demon Copperhead, these narratives generally describe how individuals end up misusing painkillers due to accident-related injuries and become addicted over time.

I suspect this narrative persists for two reasons: because those tactics really did ensnare countless people into opioid addiction before regulatory bodies caught on, and because self-evidently tragic victimhood is easy for an audience to digest. But though Perry says he started taking Vicodin after a jet ski accident, his memoir also speaks a different truth. In Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, he takes sole responsibility for his problems; he speaks candidly about the deep-seated insecurity that led him to take his first drink at 14, his insatiable hunger for fame and recognition, the relationships he ruined from adolescence on by being selfish and cruel. (Some of that behavior can be attributed to his drug use, but not all of it.)

He’s frank about the tedium of addiction—the Sisyphean effort of trying to score enough pills to get through each day, the running mental calculations necessary to stave off withdrawal symptoms—and the monotony of a life that’s forever ping-ponging between rehab and relapse. In a passage that’s stuck in my brain, just like the reunion scene, Perry writes that he’d change places with anyone else “in a minute, and forever, if only I could not be who I am, the way I am, bound on this wheel of fire. They don't have a brain that wants them dead.”

It’s dark, difficult material, the polar opposite of something as uncomplicatedly enjoyable as Friends. But it’s also insightful, the rare addiction narrative that goes beyond cliché—perhaps because Perry wrote it not to dramatize his illness, but expressly to help his fellow addicts. As a person who was paralyzed by the mere idea of his audience not laughing loudly enough at one of his jokes, it must have taken tremendous guts for Perry to reveal in writing just how unlikable addiction made him—to confess that it drove him to fly back and forth from Switzerland just to get his fix. On a private plane. During the height of COVID. Reading his book made me realize that maintaining sobriety must be a lot like processing grief—that it means persisting despite the big, terrible thing that hovers just outside your field of vision, one that’s sometimes closer to you and sometimes farther away but never fully gone.

How awful it must have been for Perry to endure it for so long. How brave he was to keep trying anyway.