2023: Charting the Record-Breaking Heat Wave

The past year didn’t just break records, it redefined them.

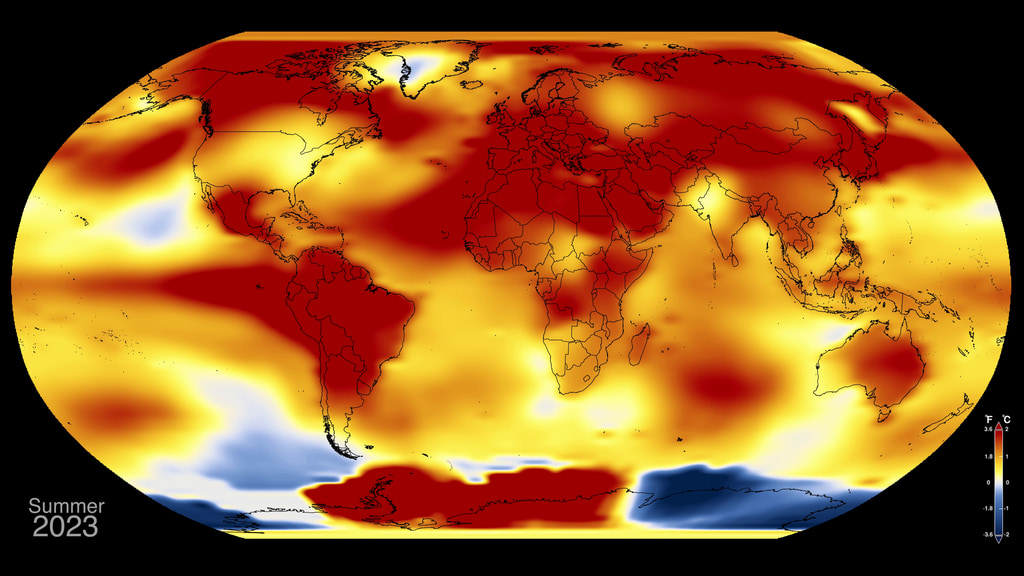

The graphs illustrating this year's high global temperatures show that the numbers in numerous regions across the globe were not only higher than ever recorded before, but the variation from the standard was extraordinarily large.

Doug McNeall from the U.K. Met Office Hadley Centre in Exeter, England commented on how the significant breaking of records this year shocked not just him but also other climate scientists, even those with conservative estimates.

By the end of November, several months of intense global temperatures have placed 2023 on course to be the Earth’s warmest year since records started about 150 years ago. The year-long period from November 2022 through October 2023 is officially the warmest such period on record, expected to be surpassed by 2024, as per the non-profit organization, Climate Central.

Extreme heatwaves affected many regions, triggering disastrous wildfires. The average ocean heat showed record levels, with global average sea surface temperatures maintaining record highs for the majority of the year. And around Antarctica, sea ice reached record lows.

These records strongly reflect the influence of human-induced climate change, as stated by the scientific consortium World Weather Attribution. Climate change increased the possibility of July’s extreme heatwaves in North America, Southern Europe, and North Africa hundreds of times, and similarly contributed to a rise of about 50 times in China. Climate change was also the main driver behind a harsh winter and early spring heatwave in South America.

Many climate scientists on social media struggled to articulate their reactions to such shocking temperature anomalies of 2023.

Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading in England, shared a list of expletives on X, formerly known as Twitter, pertaining to September’s air temperatures.

From January to September, the Earth’s average global surface air temperature was about 1.1 degrees Celsius (nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit) more than the 20th century average of 14.1° C (57.5° F).

The months from June to October were the hottest ever recorded for those months, with September being hotter than an average July from 2001 to 2010. Current temperatures imply a more than 99 percent likelihood that 2023 will be the hottest year on record, as per the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information.

The average of daily air temperatures in 2023 experienced exceptional spikes during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer months, reaching past global temperatures recorded each year since 1981.

Parts of Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina, in the Southern Hemisphere underwent an especially torrid winter and early spring, with temperatures in August and September soaring above 40° C (104° F). In some regions, daytime temperatures were about 20 degrees C (36 degrees F) above the usual. Even Madagascar experienced its warmest October on record, with some areas being 2.5 degrees C (4.5 degrees F) over average.

The latter part of 2023 saw the introduction of an El Niño climate pattern, which usually implies higher global temperatures, according to John Kennedy, a climate scientist with the U.N. World Meteorological Organization. However, he notes that most warming associated with this event is usually seen the following year, akin to what occurred in 2016, which was previously the hottest year on record.

Ocean temperatures started breaking records long before El Niño started. From March end to October, the global average sea surface temperature consistently broke daily records. By July, these temperatures were near 1 degree C (about 1.8 degrees F) above average, as nearly half of the global ocean experienced marine heatwaves, in contrast to the usual 10 percent.

From late March onwards, 2023’s average ocean surface temperatures were higher for latitudes from 60° N to 60° S than in any year since 1981 at least.

Such high temperatures are unparalleled in the modern record — and perhaps in the last 125,000 years, researchers note. Such consistent accumulation of heat has devastatingly impacted ocean life. Coral reefs, for example, faced extensive bleaching in the Gulf of Mexico, the northern Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern Pacific Ocean.

The news has frequently reported exceptional daytime temperature highs, but these record-breaking temperatures often persist into the night, which can pose a threat to human health.

The nighttime high in Adrar, Algeria reached a never-before-seen 39.6° C (103.3° F) on July 6, demonstrating the hottest evening on record in Africa. In a continuation of this trend, a temperature of 48.9° C (120° F) was documented in Death Valley, Calif., slightly after midnight on July 17, and this could potentially be the highest known temperature for that specific hour anywhere in the world.

Global trends show that night temperatures have been increasing more than daytime temperatures for many years; this is problematic as it robs the body of the chance to recover from daytime heat.

Improved sleep conditions are linked with cooler night-time temperatures. According to a study conducted by data scientist Kelton Minor of Columbia University and team in 2017, warmer nights have reduced sleep by approximately 44 hours per individual each year. Minor suggests that the extreme heat experienced this year is likely to have further reduced sleep duration.

Aside from affecting sleep, extreme heat can also increase the risk of health issues such as heat stroke, cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, and in some severe cases, can even cause death. In fact, the number of fatalities due to heat have been escalating for years.

Despite the known dangers of severe heat, the number of lives it claims is still not known in many parts of the world, including Africa. However, according to an analysis of Eurostat data, over 60,000 people died due to extreme heat in Europe last year, a significant increase from the approximately 40,000 deaths in 2018. Preliminary data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that heat was the cause of death for over 1,700 people in the United States in 2022 - this is quadruple the corresponding figure from eight years ago.

With hundreds of heat-related deaths reported by October in multiple counties in the American Southwest, 2023 seemed to continue the pattern. For instance, in Arizona's Maricopa County alone, 579 deaths were reported, in comparison to the 386 fatalities in 2022.

Kristie Ebi, a climate and health researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle, puts this down to a lack of awareness regarding the dangers of heat. She emphasizes that it is important to enhance awareness about these risks and take precautionary measures such as creating cooling centers and urban green spaces.

Higher night-time temperatures can also enhance the spread of wildfires. In the past, a drop in temperature during the night helped to control the spread of wildfires. However, present-day temperatures during a heatwave do not drop significantly at night which means wildfires can continue to spread.

The heat this year led to particularly intense fire activity in the Boreal region, a large area located slightly south of the Arctic Circle and home to almost a third of the world's forests. The biggest portion of this forest lies in Canada, which recently reported its worst year of wildfires.

Hundreds of huge fires swept across the country, prompting the evacuation of around 200,000 people due to advancing flames. In Quebec, heavy smoke from fires spread as far as the U.S. East Coast and Midwest, blanketing these areas in an orange haze and lowering air quality drastically. By October, the area that was burnt in Canada exceeded 180,000 square kilometers, over double the previous national record from 1995.

Wildfires increase carbon emissions, further contributing to global warming. Carbon emissions from the fires in Canada alone were estimated to amount to almost 410 million metric tons, constituting more than a quarter of the global wildfire emissions this year.

As a whole, though, 2023’s wildfire emissions didn’t break global records. In fact, wildfire emissions have been decreasing for decades, largely because humans have cleared away many forested areas for agriculture, ultimately decreasing the total area where wildfires could burn (SN: 6/16/23).

Nonetheless, terrifying wildfires scorched many parts of the world.

In the Northern Hemisphere, summer heat contributed to a wildfire in Greece that became the largest ever recorded in the European Union. In Hawaii, a wildfire fueled in part by drought destroyed much of the town of Lahaina and left at least 99 dead, making it the deadliest U.S. wildfire since 1918.

Meanwhile, the Southern Hemisphere’s warm winter helped fires spread in many regions including Argentina and the Amazon rainforest. In Australia, an unusual spring heatwave helped the fire season kick off early; by August, around 70 blazes had already been reported out of New South Wales, the country’s most populated state, two months before the official start of the bushfire season in that state.

Dwindling sea ice in the Arctic has become a familiar story in recent decades, while the southernmost continent’s sea ice has waxed and waned more erratically.

But in the last few years, satellite data have shown an uptick in the rate of Antarctic sea ice loss, says climate scientist Mark Serreze, director of the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo.

Then came 2023. Antarctica’s sea ice “just plummeted,” Serreze says.

The sea ice expanse was at near record-low levels for much of the year (SN: 7/5/23). February, the peak of summer, saw a record low minimum extent. By late July, the height of winter, the sea ice was more than 2.6 million square kilometers below the 1981–2010 average. On September 10, the sea ice extent hit its annual maximum at about 17 million square kilometers. That’s roughly 1 million square kilometers smaller than the previous lowest maximum in 1986.

These numbers were “far outside anything observed in the 45-year modern satellite record,” Serreze says.

The expanse of sea ice surrounding Antarctica has remained at record low levels for nearly all of 2023 (red), reaching its lowest point in February, the height of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer. In September, when Antarctic sea ice typically reaches its largest extent, the sea ice was far below the 1981–2022 median (black).

El Niño and other regional climate patterns probably played a role. Shifting ocean circulation or wind directions could have either packed the ice in or shuttled it farther out to sea. But growing evidence suggests that warmer ocean waters may also be complicit, Serreze says.

Whatever the case, this year’s trail of shattered records has made it clearer than ever that human-caused climate change is not a problem for tomorrow. “We’re standing in the aftermath of one of the biggest waves in the climate system in recent history,” Minor says, “and we need to also prepare for bigger waves that are approaching.”