Le ricerche precoci sull'mRNA che hanno portato ai vaccini COVID-19 vincono il Premio Nobel per la Medicina del 2023.

Due scienziati che hanno gettato le basi per quello che sarebbe diventato uno dei vaccini più influenti di tutti i tempi sono stati premiati nel 2023 con il Premio Nobel per la medicina o la fisiologia.

La biochimica Katalin Karikó, attualmente presso l'Università di Szeged in Ungheria, e Drew Weissman dell'Università della Pennsylvania sono stati premiati per le loro ricerche sulle modifiche dell'mRNA che hanno reso possibili i primi vaccini contro il COVID-19 (SN: 12/15/21).

"Tutti hanno sperimentato la pandemia di COVID-19 che influisce sulla nostra vita, economia e salute pubblica. È stato un evento traumatico", ha dichiarato Qiang Pan-Hammarström, membro dell'Assemblea Nobel presso l'Istituto Karolinska di Stoccolma, che assegna il premio per la medicina o la fisiologia. Le sue osservazioni sono state fatte il 2 ottobre dopo una conferenza stampa per annunciare i vincitori. "Probabilmente non c'è bisogno di sottolineare ulteriormente che la scoperta fondamentale fatta dai premi Nobel ha avuto un enorme impatto sulla nostra società".

Al settembre 2023, secondo l'Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità, sono state somministrate più di 13,5 miliardi di dosi di vaccino contro il COVID-19, compresi i vaccini a base di mRNA e altri tipi di vaccini, sin dalla loro disponibilità nel dicembre 2020. Nell'anno successivo alla loro introduzione, si stima che i vaccini abbiano salvato quasi 20 milioni di vite in tutto il mondo. Negli Stati Uniti, dove la maggior parte dei vaccini COVID-19 a base di mRNA prodotti da Moderna e Pfizer/BioNTech sono stati somministrati, si stima che abbiano evitato 1,1 milioni di morti aggiuntive e 10,3 milioni di ricoveri ospedalieri.

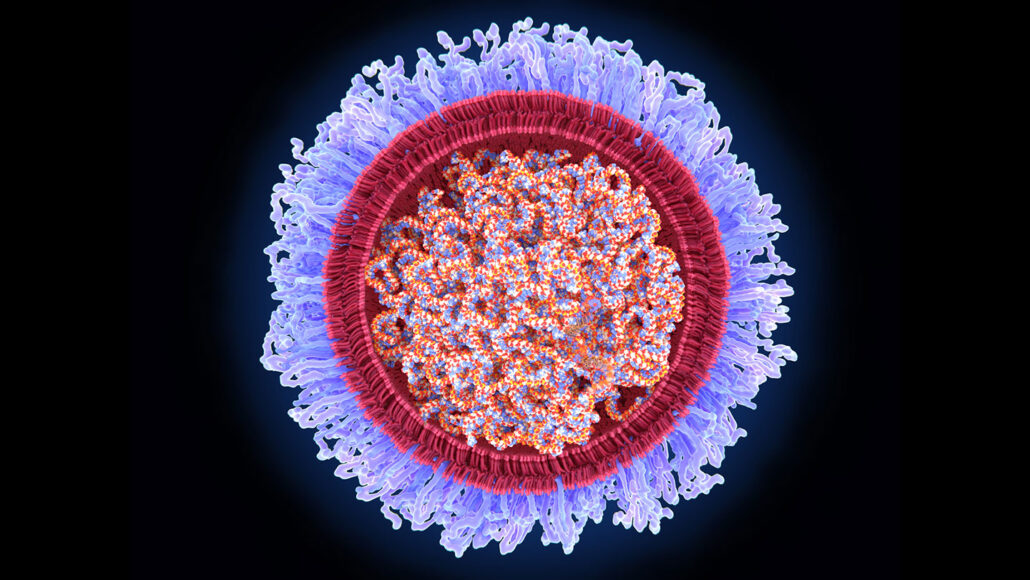

L'mRNA è il parente chimico meno conosciuto del DNA. Le cellule producono copie di RNA di istruzioni genetiche contenute nel DNA. Alcune di queste copie di RNA, chiamate mRNA, vengono utilizzate per costruire proteine. L'mRNA messaggero "dice letteralmente alle cellule quali proteine produrre", dice Kizzmekia Corbett-Helaire, immunologa virale presso la Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health di Boston. Le proteine svolgono gran parte del lavoro importante che mantiene vive e in salute le cellule e gli organismi di cui fanno parte.

I vaccini a base di mRNA funzionano in modo leggermente diverso rispetto alle immunizzazioni tradizionali. La maggior parte dei vaccini tradizionali utilizza virus o batteri, debilitati o uccisi, o proteine da tali agenti patogeni per provocare il sistema immunitario a produrre anticorpi protettivi e altre difese contro future infezioni.

Al contrario, i vaccini COVID-19 prodotti da Pfizer/BioNTech e Moderna contengono mRNA che porta le istruzioni per la produzione di una delle proteine del coronavirus (SN: 2/21/20). Quando una persona riceve un'iniezione di mRNA, il materiale genetico penetra nelle sue cellule e avvia la produzione della proteina virale per un breve periodo di tempo. Quando il sistema immunitario riconosce la proteina virale, costruisce difese per prevenire malattie gravi se la persona viene successivamente infettata dal coronavirus.

I vaccini a base di mRNA sono stati una buona scelta per combattere la pandemia, dice Corbett-Helaire. La tecnologia permette agli scienziati di "saltare il passaggio di produrre grandi quantità di proteine in laboratorio e invece ... dire al corpo di fare cose che il corpo fa già, tranne che ora produciamo una proteina in più", dice.

Oltre a proteggere le persone dal coronavirus, i vaccini a base di mRNA potrebbero anche funzionare contro altre malattie infettive e il cancro. Gli scienziati potrebbero anche utilizzare la tecnologia per aiutare le persone affette da determinate malattie genetiche rare a produrre enzimi o altre proteine che mancano loro. Sono in corso sperimentazioni cliniche per molti di questi utilizzi, ma potrebbe passare molto tempo prima che gli scienziati conoscano i risultati (SN: 12/17/21).

Il primo vaccino a base di mRNA per il COVID-19 è diventato disponibile poco meno di un anno dopo l'inizio della pandemia, ma la tecnologia alla sua base è stata sviluppata per decenni.

Ricevi un'ottima divulgazione scientifica, dalla fonte più affidabile, consegnata al tuo domicilio.

Nel 1997, Karikó e Weissman si sono incontrati alla fotocopiatrice, ha raccontato Karikó durante una conferenza stampa il 2 ottobre all'Università della Pennsylvania. Lei gli ha parlato del suo lavoro con l'RNA, e lui ha condiviso il suo interesse per i vaccini. Anche se ospitati in edifici separati, i ricercatori hanno lavorato insieme per risolvere un problema fondamentale che avrebbe potuto mettere a rischio i vaccini e le terapie a base di mRNA: l'iniezione di mRNA normale nel corpo provoca una reazione immunitaria negativa, producendo un'abbondanza di sostanze chimiche immunitarie chiamate citochine. Queste sostanze chimiche possono scatenare infiammazioni dannose. E questo mRNA non modificato produce pochissime proteine nel corpo.

I ricercatori hanno scoperto che sostituire il mattoncino di RNA uridina con versioni modificate, prima pseudouridina e poi N1-metilpseudouridina, poteva smorzare la reazione immunitaria negativa. Questa geniale chimica, segnalata per la prima volta nel 2005, ha consentito ai ricercatori di controllare la risposta immunitaria e consegnare l'mRNA in modo sicuro alle cellule.

“The messenger RNA has to hide and it has to go unnoticed by our bodies, which are very brilliant at destroying things that are foreign,” Corbett-Helaire says. “The modifications that [Karikó and Weissman] worked on for a number of years really were fundamental to allowing the mRNA therapeutics to hide while also being very helpful to the body.”

In addition, the modified mRNA produced lots of protein that could spark an immune response, the team showed in 2008 and 2010. It was this work on modifying mRNA building blocks that the prize honors.

For years, “we couldn’t get people to notice RNA as something interesting,” Weissman said at the Penn news conference. Vaccines using the technology failed clinical trials in the early 1990s, and most researchers gave up. But Karikó “lit the match,” and they spent the next 20 years figuring out how to get it to work, Weissman said. “We would sit together in 1997 and afterwards and talk about all the things that we thought RNA could do, all of the vaccines and therapeutics and gene therapies, and just realizing how important it had the potential to be. That’s why we never gave up.”

In 2006, Karikó and Weissman started a company called RNARx to develop mRNA-based treatments and vaccines. After Karikó joined the German company BioNTech in 2013, she and Weissman continued to collaborate. They and colleagues reported in 2015 that encasing mRNA in bubbles of lipids could help the fragile RNA get into cells without getting broken down in the body. The researchers were developing a Zika vaccine when the pandemic hit, and quickly applied what they had learned toward containing the coronavirus.

The duo’s work was not always so celebrated. Thomas Perlmann, Secretary General of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, asked the newly minted laureates whether they were surprised to have won. He said that Karikó was overwhelmed, noting that just 10 years ago she was terminated from her job and had to move to Germany without her family to get another position. She never won a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to support her work.

“She struggled and didn’t get recognition for the importance of her vision,” Perlmann said, but she had a passion for using mRNA therapeutically. “She resisted the temptation to sort of go away from that path and do something maybe easier.” Karikó is the 61st woman to win a Nobel Prize since 1901, and the 13th to be awarded a prize in physiology and medicine.

Though it often takes decades before the Nobel committees recognize a discovery, sometimes recognition comes relatively swiftly. For instance, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2020 a mere eight years after the researchers published a description of the genetic scissors CRISPR/Cas 9 (SN: 10/7/20).

“I never expected in my entire life to get the Nobel Prize,” Weissman said, especially not a mere three years after the vaccines demonstrated their medical importance. Perlmann told him the Nobel committee was seeking to be “more current” with its awards, he said.

The timely Nobel highlights that “there are just a million other possibilities for messenger RNA therapeutics … beyond the vaccines,” Corbett-Helaire says.

The researchers said at the Penn news conference that they weren’t sure the early morning phone call from Perlmann was real. On the advice of Weissman’s daughter, they waited for the Nobel announcement. “We sat in bed. [I was] looking at my wife, and my cat is begging for food,” he said. “We wait, and the press conference starts, and it was real. So that’s when we really became excited.”

Karikó and Weissman will share the prize of 11 million Swedish kronor, or roughly $1 million.

Our mission is to provide accurate, engaging news of science to the public. That mission has never been more important than it is today.

As a nonprofit news organization, we cannot do it without you.

Your support enables us to keep our content free and accessible to the next generation of scientists and engineers. Invest in quality science journalism by donating today.