Investigaciones tempranas de ARNm que condujeron a las vacunas contra el COVID-19 ganan el Premio Nobel de Medicina 2023.

Dos científicos que sentaron las bases para lo que se convertiría en una de las vacunas más influyentes de todos los tiempos han sido galardonados con el Premio Nobel de medicina o fisiología 2023.

La bioquímica Katalin Karikó, ahora en la Universidad de Szeged en Hungría, y Drew Weissman de la Universidad de Pensilvania fueron honrados por su investigación sobre modificaciones del ARNm que hicieron posible las primeras vacunas contra el COVID-19 (SN: 12/15/21).

"Todo el mundo ha experimentado la pandemia de COVID-19 que afecta nuestra vida, economía y salud pública. Fue un evento traumático", dijo Qiang Pan-Hammarström, miembro de la Asamblea Nobel en el Instituto Karolinska en Estocolmo, que otorga el premio de medicina o fisiología. Sus declaraciones fueron hechas el 2 de octubre después de una conferencia de prensa para anunciar a los ganadores. "Probablemente no necesite enfatizar más que el descubrimiento básico realizado por los galardonados ha tenido un gran impacto en nuestra sociedad".

Hasta septiembre de 2023, se habían administrado más de 13.500 millones de dosis de vacunas contra el COVID-19, incluyendo vacunas de ARNm y otros tipos de vacunas, desde que estuvieron disponibles por primera vez en diciembre de 2020, según la Organización Mundial de la Salud. En el año siguiente a su introducción, se estima que las vacunas han salvado casi 20 millones de vidas en todo el mundo. En Estados Unidos, donde las vacunas de ARNm COVID-19 fabricadas por Moderna y Pfizer/BioNTech representaron la gran mayoría de las vacunaciones, se estima que las vacunas han evitado 1,1 millones de muertes adicionales y 10,3 millones de hospitalizaciones.

El ARN es el primo químico menos conocido del ADN. Las células hacen copias de ARN de las instrucciones genéticas contenidas en el ADN. Algunas de esas copias de ARN, conocidas como ARN mensajero o ARNm, se utilizan para construir proteínas. El ARN mensajero "literalmente le dice a tus células qué proteínas hacer", dice Kizzmekia Corbett-Helaire, inmunóloga viral en la Escuela de Salud Pública Harvard T. H. Chan en Boston. Las proteínas realizan gran parte del trabajo importante que mantiene vivas y saludables a las células y a los organismos de los que forman parte.

Las vacunas de ARNm funcionan de manera un poco diferente que las inmunizaciones tradicionales. La mayoría de las vacunas tradicionales utilizan virus o bacterias, ya sea debilitadas o inactivadas, o proteínas de esos patógenos para provocar que el sistema inmunológico produzca anticuerpos protectores y otras defensas contra infecciones futuras.

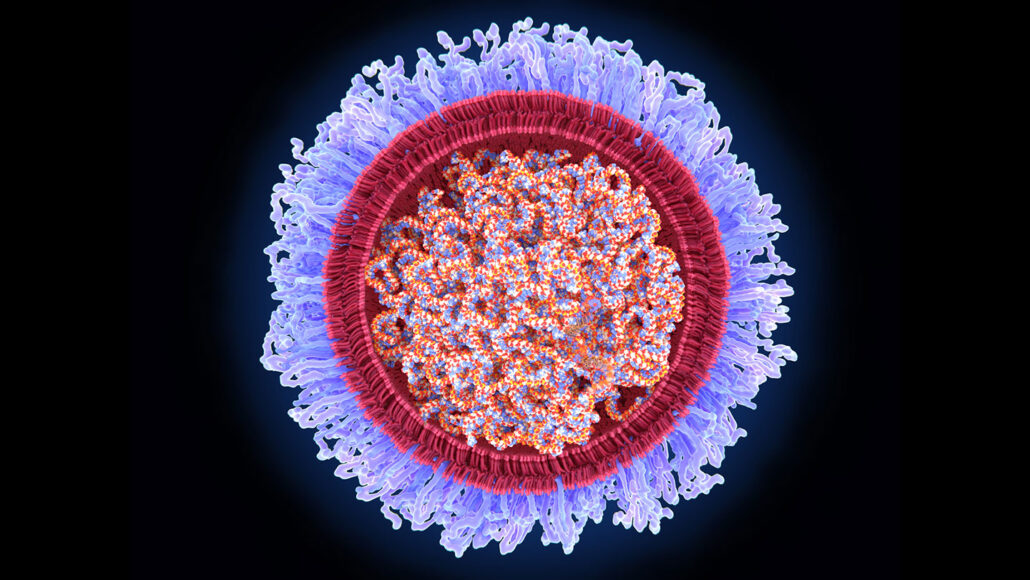

Las vacunas contra el COVID-19 fabricadas por Pfizer/BioNTech y Moderna en su lugar contienen ARNm que lleva instrucciones para fabricar una de las proteínas del coronavirus (SN: 2/21/20). Cuando una persona recibe una vacuna de ARNm, el material genético entra en sus células y provoca que las células produzcan la proteína viral durante un corto período de tiempo. Cuando el sistema inmunológico ve la proteína viral, construye defensas para evitar enfermedades graves si la persona se infecta más tarde con el coronavirus.

Las vacunas que utilizan ARNm fueron una buena elección para combatir la pandemia, dice Corbett-Helaire. La tecnología permite a los científicos "omitir el paso de producir grandes cantidades de proteínas en el laboratorio y en su lugar... decirle al cuerpo que haga cosas que el cuerpo ya hace, excepto que ahora hacemos una proteína adicional", dice ella.

Además de proteger a las personas del coronavirus, las vacunas de ARNm también pueden funcionar contra otras enfermedades infecciosas y el cáncer. Los científicos también podrían utilizar la tecnología para ayudar a las personas con ciertas enfermedades genéticas raras a producir enzimas u otras proteínas que les faltan. Se están realizando ensayos clínicos para muchos de estos usos, pero podrían pasar años antes de que los científicos conozcan los resultados (SN: 12/17/21).

La primera vacuna de ARNm para el COVID-19 estuvo disponible justo antes de cumplirse un año de la pandemia, pero la tecnología detrás de ella lleva décadas en desarrollo.

Obtén un gran periodismo científico, de la fuente más confiable, entregado a tu puerta.

En 1997, Karikó y Weissman se conocieron en la fotocopiadora, dijo Karikó durante una conferencia de prensa el 2 de octubre en la Universidad de Pensilvania. Ella le habló de su trabajo con el ARN, y él compartió su interés en las vacunas. Aunque estaban en edificios separados, los investigadores trabajaron juntos para resolver un problema fundamental que podría haber obstaculizado las vacunas y terapias de ARNm: La introducción de ARNm regular en el cuerpo provoca una reacción inmune perjudicial, produciendo una avalancha de productos químicos inmunes llamados citoquinas. Esos productos químicos pueden desencadenar una inflamación dañina. Y este ARNm no modificado produce muy poca proteína en el cuerpo.

Los investigadores descubrieron que sustituir el bloque de construcción de ARN uridina por versiones modificadas, primero pseudouridina y luego N1-metilpseudouridina, podría atenuar la reacción inmune perjudicial. Esa ingeniosa química, informada por primera vez en 2005, permitió a los investigadores controlar la respuesta inmunológica y entregar con seguridad el ARNm a las células.

“The messenger RNA has to hide and it has to go unnoticed by our bodies, which are very brilliant at destroying things that are foreign,” Corbett-Helaire says. “The modifications that [Karikó and Weissman] worked on for a number of years really were fundamental to allowing the mRNA therapeutics to hide while also being very helpful to the body.”

In addition, the modified mRNA produced lots of protein that could spark an immune response, the team showed in 2008 and 2010. It was this work on modifying mRNA building blocks that the prize honors.

For years, “we couldn’t get people to notice RNA as something interesting,” Weissman said at the Penn news conference. Vaccines using the technology failed clinical trials in the early 1990s, and most researchers gave up. But Karikó “lit the match,” and they spent the next 20 years figuring out how to get it to work, Weissman said. “We would sit together in 1997 and afterwards and talk about all the things that we thought RNA could do, all of the vaccines and therapeutics and gene therapies, and just realizing how important it had the potential to be. That’s why we never gave up.”

In 2006, Karikó and Weissman started a company called RNARx to develop mRNA-based treatments and vaccines. After Karikó joined the German company BioNTech in 2013, she and Weissman continued to collaborate. They and colleagues reported in 2015 that encasing mRNA in bubbles of lipids could help the fragile RNA get into cells without getting broken down in the body. The researchers were developing a Zika vaccine when the pandemic hit, and quickly applied what they had learned toward containing the coronavirus.

The duo’s work was not always so celebrated. Thomas Perlmann, Secretary General of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, asked the newly minted laureates whether they were surprised to have won. He said that Karikó was overwhelmed, noting that just 10 years ago she was terminated from her job and had to move to Germany without her family to get another position. She never won a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to support her work.

“She struggled and didn’t get recognition for the importance of her vision,” Perlmann said, but she had a passion for using mRNA therapeutically. “She resisted the temptation to sort of go away from that path and do something maybe easier.” Karikó is the 61st woman to win a Nobel Prize since 1901, and the 13th to be awarded a prize in physiology and medicine.

Though it often takes decades before the Nobel committees recognize a discovery, sometimes recognition comes relatively swiftly. For instance, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2020 a mere eight years after the researchers published a description of the genetic scissors CRISPR/Cas 9 (SN: 10/7/20).

“I never expected in my entire life to get the Nobel Prize,” Weissman said, especially not a mere three years after the vaccines demonstrated their medical importance. Perlmann told him the Nobel committee was seeking to be “more current” with its awards, he said.

The timely Nobel highlights that “there are just a million other possibilities for messenger RNA therapeutics … beyond the vaccines,” Corbett-Helaire says.

The researchers said at the Penn news conference that they weren’t sure the early morning phone call from Perlmann was real. On the advice of Weissman’s daughter, they waited for the Nobel announcement. “We sat in bed. [I was] looking at my wife, and my cat is begging for food,” he said. “We wait, and the press conference starts, and it was real. So that’s when we really became excited.”

Karikó and Weissman will share the prize of 11 million Swedish kronor, or roughly $1 million.

Our mission is to provide accurate, engaging news of science to the public. That mission has never been more important than it is today.

As a nonprofit news organization, we cannot do it without you.

Your support enables us to keep our content free and accessible to the next generation of scientists and engineers. Invest in quality science journalism by donating today.