The native language shapes the wiring of your brain

Our native language appears to have a biological impact on our brains that endures over time, according to a report from researchers. The report, which was published in NeuroImage on February 19th, observed distinct differences in connection strengths in specific areas of the brain’s language circuit. The study was performed on nearly 100 brain scans, making it one of the first in which such structural wiring differences have been identified among a large group of monolingual adults.

Alfred Anwander, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, stated that "the specific difficulties [of each language] leave distinct traces in the brain. So we are not the same if we learn to speak one language, or if we learn another."

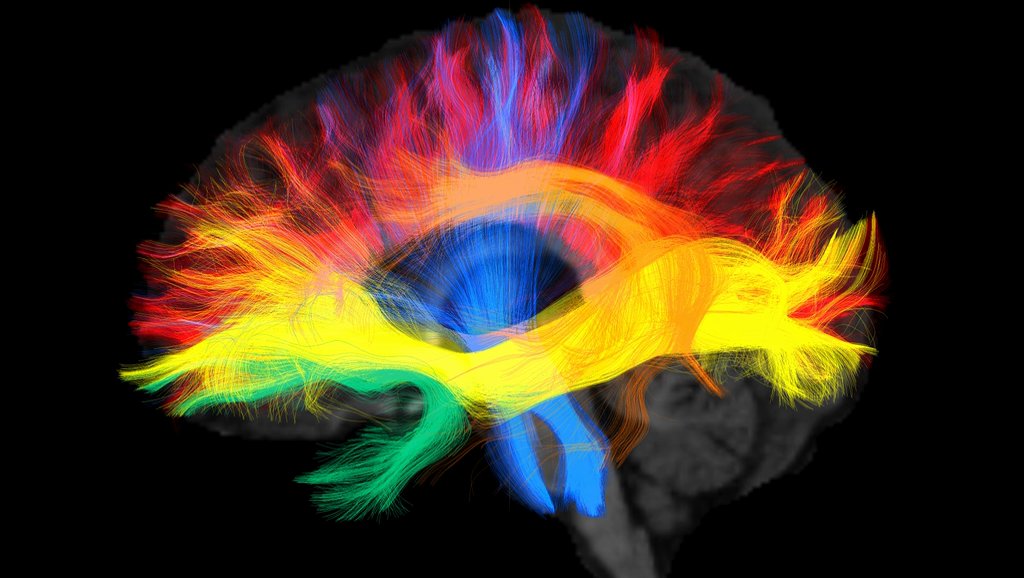

Every human language uses a different combination of systems. Our brains process these systems in multiple brain regions connected by white matter. This tissue links nerve cells throughout the brain, enabling routes for communication throughout. Creating connections between brain regions in this way is hugely important for learning: repeated use reinforces connections to increase their durability.

The study found that every language has its own difficulties, which resulted in different white matter networks. The team recruited 94 healthy volunteers, with German or Levantine Arabic as their native languages, for structural MRI brain scans. The scans revealed that Arabic speakers tended to have stronger connections across their left and right hemispheres, whereas German speakers had a denser network of connections within the left hemisphere.

The potentially confusing nature of Arabic’s root words and the fact that Arabic script reads from right to left are responsible for this difference in brain activity. German, with its complex and flexible word order, allows for the creation of temporal subtleties. This could account for the German speakers’ denser white matter networks for parsing word order. However, the researchers suggested that the Arabic speakers’ relative newness to Germany could have also altered their white matter networks.

The study focused solely on language circuits, however parts of those circuits had diverse functions. As a result, language learning could change non-linguistic regions of the brain too.

It’s still controversial whether language-associated white matter rewiring affects more than just language, Anwander says. But at least within the language circuit, the new results hint that our mother tongues are far more than just the words we happened to grow up with — they are quite literally a part of us.

Our mission is to provide accurate, engaging news of science to the public. That mission has never been more important than it is today.

As a nonprofit news organization, we cannot do it without you.

Your support enables us to keep our content free and accessible to the next generation of scientists and engineers. Invest in quality science journalism by donating today.