The Babies of These Live-Birthing Snails May be the Ones Doing the Work

A small number of animals do not lay eggs, including the resilient little snail known as the rough periwinkle.

This creature, which resides in the intertidal zone, has recently evolved to give birth to live young, rather than laying eggs like most other animals. The unconventional nature of the rough periwinkle's birthing process involves the mother snail giving birth several times a day, and the newborns themselves are likely responsible for much of the labour involved in birth.

The egg-laying relatives of the rough periwinkle possess a jelly gland that produces a secure mass of eggs external to the mother’s body, however, in the species Littorina saxatilis, this gland changes into a form of womb or brood pouch. In this case, the eggs develop within the body of the mother until they hatch, according to evolutionary ecologist Kerstin Johannesson from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

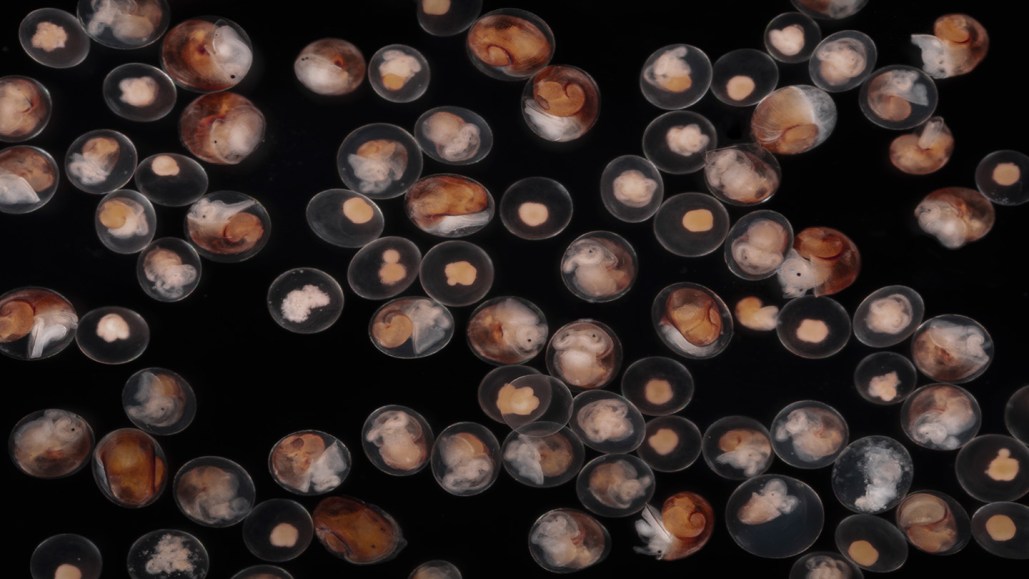

The mother snail can host hundreds of embryos in varying states of development at a time. Johannesson suggests that the young snails possibly make their own way into the world, rather than being actively pushed out by the mother.

Prior to exiting from the brood pouch, each baby snail scrapes a hole into its transparent eggshell-like covering, in a manner similar to a hatching bird. The baby snails then find their way out of their mother’s body, although how they locate the exit remains unknown — Johannesson speculates that they may be able to sense the presence of saltwater from outside.

The live birth feature of these snails is intriguing to researchers like Johannesson, as the species likely acquired this ability relatively recently in evolutionary terms — approximately within the last 100,000 years.

Comparisons between the rough periwinkle and two closely related species (L. arcana and L. compressa) reveal that giving birth to live young is the unique trait distinguishing these species.

Sean Stankowski, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Sussex, delved into the genetic complexity of these species to gain insight into how one egg-laying lineage resulted in live birth. Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that the shift to live birth doesn’t appear to result from a dramatic genetic shift. Rather, incremental changes in approximately 50 regions of the snail’s genes accounted for this major evolutionary transition.

The act of giving extra protection to their eggs may explain the success of this species, despite the tiny size of the newborns. Newborn rough periwinkles are minuscule, measuring only half a millimeter in length at birth, and can be felt like grains of sand between the fingers. They emerge on their own, sometimes even seen crawling around on their mother's shell, where they find their first meal — diatoms and bacteria present on the shell itself.