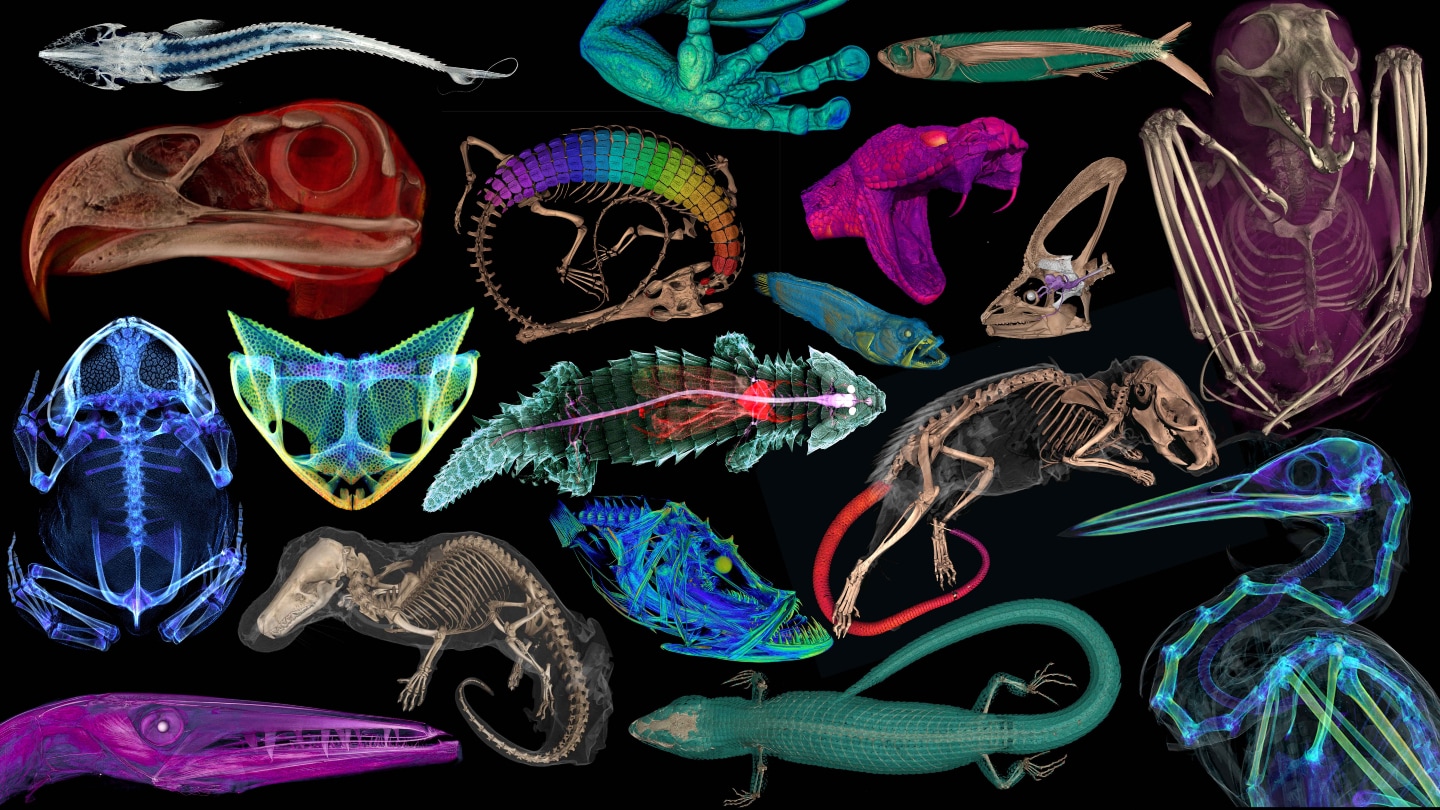

Explore 3-D animal anatomy models from openVertebrate’s public collection

Mouse tails, frog parts, and lizard scales, to name a few, are among the more than 13,000 specimens that have undergone CT scanning in a museum. This six-year project, known as openVertebrate or oVert, was geared towards building 3-D digital models of these specimens, which were usually stored until displayed to the public, or studied by a specialist. The outcome was announced on March 6 in BioScience.

The digital replicas serve multiple purposes. They not only make these collections available to wider audiences but also provide them with insights into the anatomy of these animals without dissection equipment.

"The most striking aspect is the unexpected findings that become evident, such as parasitic infections, last meals and new views into animal anatomy," comments evolutionary biologist Edward Stanley from the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

For, the CT scans revealed that the inner ears of pumpkin toadlets were so malformed that their hops ended in crash-landings. Moreover, Stanley and his team discovered that the tails of spiny mice were covered by an bony coat similar to that of an armadillo.

As part of oVert, Stanley and researchers from 25 institutions CT scanned fluid-preserved specimens, representing over half of all known vertebrate genera. This included chameleons, frogs, bats, lizards, snakes, eagles and more. Certain animals were treated with iodine to make internal organs and muscles visible.

Researchers involved in the openVertebrate initiative built an online database of more than 13,000 CT scans of various museum specimens. The objective was to provide increased researchers access to these specimens without requiring them to travel or transport the precious pieces. The public also gained access. This is a small glimpse of what these scans divulged.

Each specimen was positioned in a tube which was then spun around a fixed X-ray scanner that captured the full image of the animal's body. However, as few vertebrates are tube shaped, the team had to pad the cylinder with items that could hold the specimen without affecting the scan.

"Items like bubble wrap, packing peanuts, and plastic Coke bottles turned out to do the trick," says Stanley.

The researchers suggest that this technique could aid in digitizing other specimens stored in natural history collections, including plants and invertebrates. Certain scanners can even be used on living vertebrates, they point out.