Understanding the Significance of Investigating Trophic Behavior in Local Predators: Delving into Today's Menu

Feature dated December 28, 2023

Science X's editorial team has reviewed and validated this article based on the following criteria:

- fact verification

- reliance on dependable sources

- in-depth proofreading

Authored by Stephanie Baum, Phys.org

The scope of trophic ecology encompasses the study of food chains. In Tenerife, Canary Islands, feral cats predominantly prey on rabbits, mice, rats, and the island's native avians and reptiles. However, research indicates a significant diet shift in these wild cats since 1986, potentially threatening some indigenous species.

Mammal Research published a paper titled 'Shifts in the trophic ecology of feral cats in the alpine ecosystem of an oceanic island: implications for the conservation of native biodiversity.' The authors from Universidad de La Laguna in Tenerife argue for more attention to the subject.

Across the globe, free-roaming cats are among the most dangerous predators, with their predatory impacts being significantly amplified on islands. In this regard, it's essential to mention a 2011 study which attributes 14% of worldwide island fauna extinctions to predatory cats.

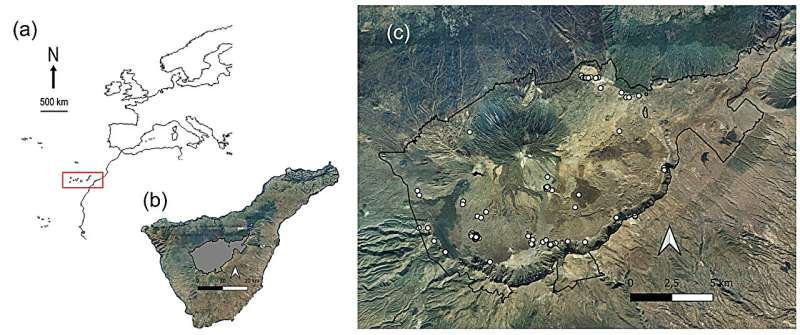

The Canary Islands archipelago is located within Macaronesia in the North Atlantic Ocean, near Morocco and the Western Sahara. A plethora of various environments is present on Tenerife, the largest island in the cluster. It includes sandy coastlines, cloud forests, pine forests, and, in the highest altitudes, alpine scrub, home to many endemic and highly varied species, present only in small numbers.

The delicate balance of the alpine scrub ecosystem beckons for concern due to the possible impact of climate change and the introduction of non-native species, including cats. These elements put the limited local fauna at high risk.

Feral cats in the region were shown in previous studies to primarily consume non-native mammals, such as rabbits, mice, rats, and also native birds and reptiles.

Research conducted in 2021 within Tenerife's southern coastal region detailed an increase in the consumption of native reptiles and birds by feral cats over the last 15 years and a simultaneous decrease in rabbit consumption.

The same study considered whether a similar dietary shift could be observed in other parts of the island over a longer 35-year span. Fieldwork in El Teide National Park, a notably abundant area of alpine scrub, revealed some startling results.

In 1986, rabbit biomass made up 73% of cat diet, while in 2021 it had decreased to 53.9%. This decrease was most likely due to the depletion of rabbit population caused by diseases such as rabbit hemorrhagic virus (RHDV and RHDV2).

These findings point to an alarming trend: feral cats in the park's high mountain scrubland are now eating more native reptiles and birds than ever before. With roughly one cat per square kilometer of the park's area, the researchers estimated total annual cat predation to nearly 260,000 vertebrates, including substantial numbers of birds and reptiles.

Given that native species such as birds and reptiles make up two-thirds of these feral cats' food intake, conservation actions must be prioritized in this region.

Significantly, two of the preyed upon species, the Tenerife lizard and the ring ouzel, play crucial roles as short- and long-distance cedar seed dispersers within this habitat.

During the coldest annual period, the ring ouzel and other birds seek food and shelter in areas of cedars, making them easy targets for cats. The team suggests fencing cedar areas to keep cats away and selective trapping of cats as mitigation actions.

© 2023 Science X Network