New Discoveries in Mesopotamian Bricks Reveal the Power of Earth's Antiquated Magnetic Field

The date is December 18, 2023.

This article has undergone a thorough review in accordance with the editorial process and policies of Science X. To ensure the reliability of the content, its following qualities have been emphasized and confirmed by the editors:

- The content has been fact-checked

- Published in a peer-reviewed outlet

- Sourced from a trusted authority

- Thoroughly proofread

Contributions from renowned University College London

Researchers from University College London have made significant strides in understanding an enigmatic anomaly in Earth's magnetic field that dates back 3,000 years. These insights come from studying ancient bricks engraved with Mesopotamian kings' names.

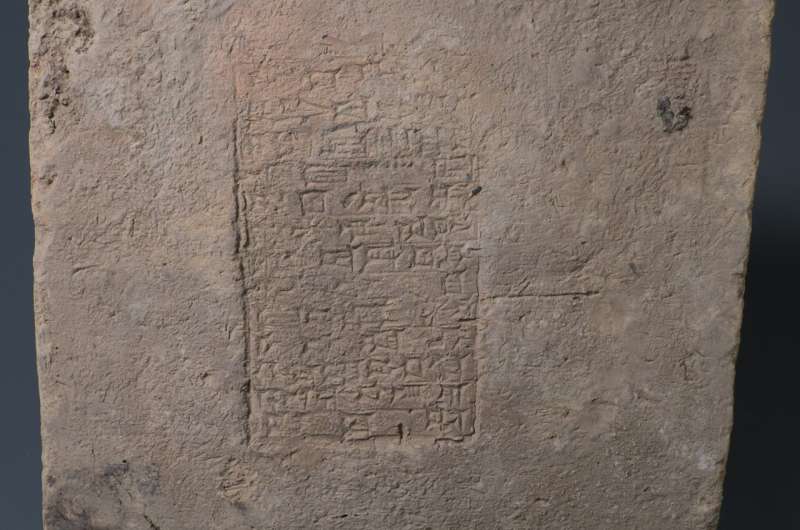

The study, printed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, explores how the Earth's magnetic field's variations imprinted on iron oxide particles in antiquated clay bricks. Using these imprints and the engraved king names for context, scientists could reproduce these magnetic changes.

The research team believes that utilizing this practice, known as 'archaeomagnetism,' could enhance the understanding of Earth's magnetic field history and assist in better dating artifacts for which prior methods were ineffective.

Professor Mark Altaweel, co-author and member of UCL Institute of Archaeology, stated that despite relying on methods like radiocarbon dating for establishing chronology in ancient Mesopotamia, it is challenging to date common cultural residues such as bricks and ceramics, which usually lack organic material. He claimed that their study introduces a beneficial dating baseline that permits absolute dating through archaeomagnetism.

Earth's magnetic field, which changes in strength over time, leaves distinctive signatures on heated minerals sensitive to the magnetic field.

The research group studied the dormant magnetic signature in iron oxide mineral grains enclosed in 32 clay bricks acquired from archaeological sites spread across Mesopotamia, now part of modern-day Iraq. The planet's magnetic field's strength was stamped on the minerals when they were initially fired by ancient brickmakers.

Each brick bore the name of the reigning king during its manufacturing, offering a probable timespan. The imprinted name, combined with the measured magnetic strength of the iron oxide grains, provided an historical representation of Earth's magnetic field strength variations over time.

The study could validate the occurrence of the 'Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic Anomaly,' an era of unusually strong magnetic field around today's Iraq from approximately 1050 to 550 BCE, although the reasons remain undetermined. While traces of the anomaly are found from places like China, Bulgaria, and the Azores, data from the Middle East has been insufficient.

According to lead author Professor Matthew Howland of Wichita State University, by juxtaposing ancient artifacts with known historical magnetic field conditions, it's feasible to estimate the dates of artifacts exposed to heat in ancient times.

The team extracted tiny fragments from the bricks to measure the iron oxide grains, using a magnetometer for exact measurement of these fragments.

This dating method also offers a new tool to archaeologists for dating ancient artifacts. The iron oxide grains' magnetic strength, embedded within fired items can be compared to the known strengths of Earth's historic magnetic field. Further, as the reigns of kings lasted from a few years to decades, the method provides better resolution than radiocarbon dating, which only locates an artifact's date within a few hundred years.

Moreover, archaeomagnetic dating can assist historians in accurately determining the reigns of ancient kings, which have been somewhat vague due to incomplete historical records. While the sequence and duration of their reigns is well-documented, there has been discord among archaeologists about the exact years the kings ascended to the throne. The researchers' technique coincides with the most accepted sequence of kings' reigns among archaeologists, known as the 'Low Chronology.'

The group also discovered that there were dramatic changes in the Earth's magnetic field during a relatively short period in five samples, taken during the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II from 604 to 562 BCE. This adds evidence to the conjecture that rapid increases in intensity are viable.

Co-author Professor Lisa Tauxe of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography said, 'The geomagnetic field is one of the most enigmatic phenomena in Earth sciences. The well-dated archaeological remains of the rich Mesopotamian cultures, especially bricks inscribed with names of specific kings, provide an unprecedented opportunity to study changes in the field strength in high time resolution, tracking changes that occurred over several decades or even less.'

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by University College London