Is the Luxury E-Commerce Sector Facing Its Demise?

Online luxury crisis: Is this the end for the biggest names in the sector?

By Sandra Halliday

Published on March 10, 2024

Matches has made almost half of its staff redundant - 273 people - as it goes through an administration seeking a buyer by insolvency specialist Teneo. The company employed 533 people across its three London stores and head office from where it sells to consumers in 170 countries. Benji Dymant, joint administrator, said: “Like many luxury fashion retailers, [it] has experienced a sharp decline in demand over the last year, due to pressures on well-publicized discretionary spending, arising of the high-inflation, high-rate macro environment. »

We had already learned from owner Frasers Group (who only bought it for £52 million just before Christmas) that it was in worse shape than expected and would need a lot of investment to turn around. And we don't know if Frasers is considering a pre-pack administration deal. “The joint administrators will continue to evaluate the appropriate structure for the business as sale discussions progress,” we were told.

So what went wrong, not just at Matches but in the wider online luxury retail sector which seemed destined to capture a growing share of luxury sales and in which UK retailers were leading names?

Difficult times

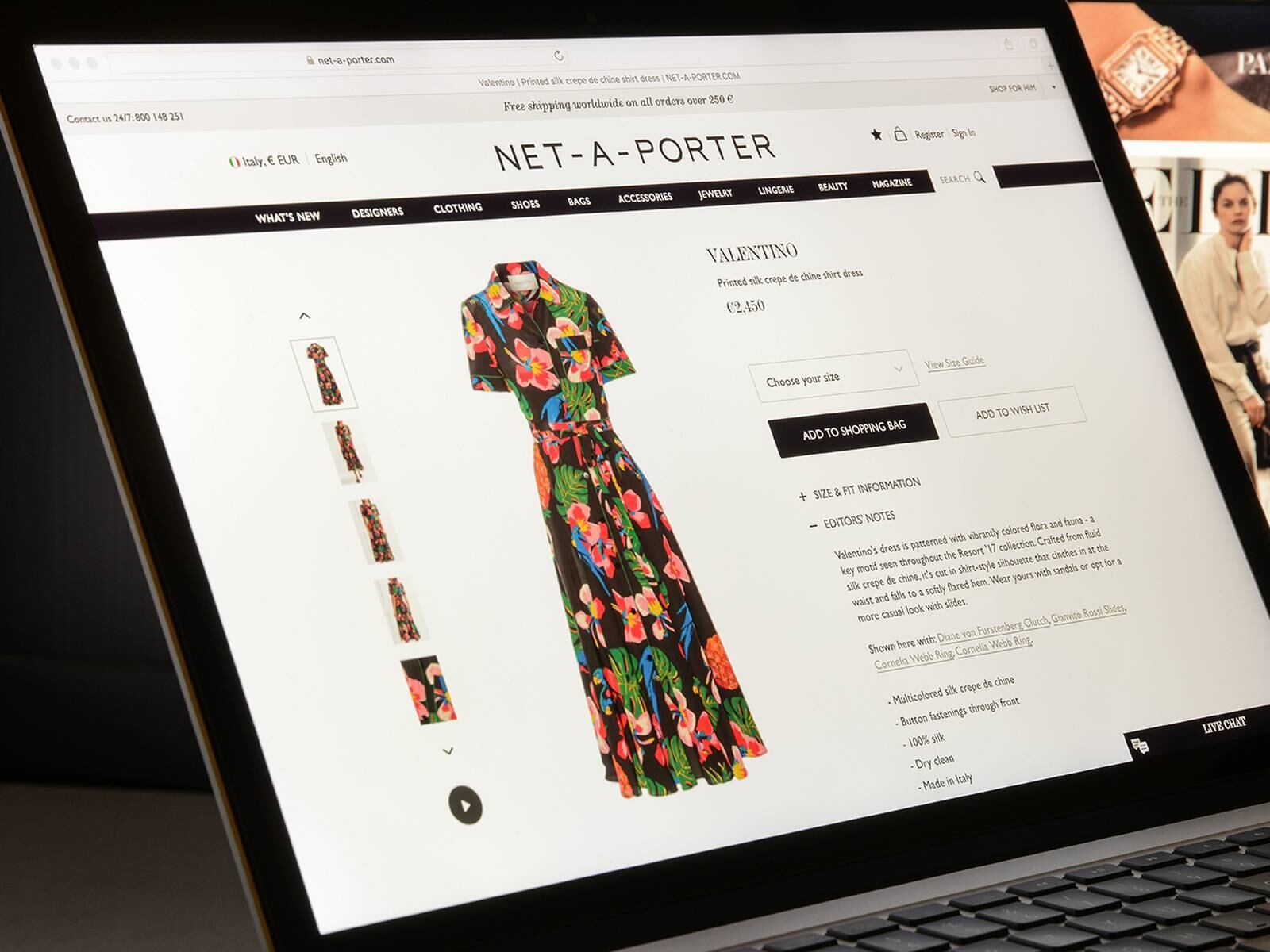

Just look at what happened. Yoox Net-A-Porter (YNAP), the part-Italian, part-British merged group was a headache for owner Richemont for years when in 2022 it struck a complex deal for Farfetch to take it over (but this would actually be “a neutral platform without a majority shareholder”). But it remains a headache because that deal collapsed.

And Farfetch was said to be close to bankruptcy before finding a savior - Coupang, who believes he can get it back on its feet for sustainable profitability. Same thing for Matches. But this time its savior took a scare with Frasers Group placing it into administration just 11 weeks after buying it.

It's all very different from the previous decade when UK-founded luxury online fashion retailers were booming. In 2015, Yoox and Net-A-Porter merged to create YNAP, a seasonal and off-price luxury retailer. Richemont liked its prospects so much that it took control of it in 2018.

In 2017, private equity giant Apax Partners reportedly paid around £800 million for Matches, leaving its founders, Ruth and Tom Chapman, “in shock”.

Then in 2018, London-based Farfetch went public on the New York Stock Exchange with a valuation heading towards $6 billion. It looked like luxury e-commerce was going to be one of the biggest growth drivers for brands that had once feared cheapening their image by selling online.

And it only got worse. The pandemic has been a boon for e-commerce with online retailers being the only ones in the game for anyone wanting to buy high-end fashion. Farfetch's José Neves spoke of a "paradigm shift towards online luxury", and Farfetch being a driver of this change.

As the pandemic subsided, many were confident that e-commerce would retain most of its market share and be poised for years of GMV revenue growth and sustainable profitability.

How wrong they were.

Alice Price, clothing industry analyst at GlobalData, summed up the situation, telling Fashionnetwork.com: “Although it is not yet clear whether Frasers Group will dissolve Matches completely or use administration to restructure the business and reduce operational costs, this news represents the latest blow for luxury marketplaces. As well as the demise of Matches, Mytheresa and Yoox Net-a-Porter continue to report declining demand, and Farfetch was acquired by Coupang in December for a fraction of its previous £20 billion valuation. »

For her, it comes down to two issues – cash-strapped aspiring buyers and brands preferring DTC over wholesale.

“Luxury marketplaces remain affected by the broader slowdown in luxury demand, particularly in Europe and the United States, as aspiring buyers continue to restrain their spending in the face of persistent inflationary pressures,” he said. she declared. “Designer brands have also begun to reduce their reliance on their wholesale partners, preferring to invest in their direct-to-consumer businesses to gain greater control over their brand image and maintain their exclusive appeal. This led to a decline in customer acquisition, with Matches turning to discounts to incentivize sales, which, in turn, impacted its margins as well as consumer perceptions. »

And fashion industry journalist and commentator Eric Musgrave believes the problems are a sign that luxury may not be as special as he thinks. “The sad saga of Matches reminds us that the luxury market is governed by the same management rules as any other sector,” he explained. “There needs to be rigorous cost control. And there isn't an endless pool of wealthy people who continue to buy things for fun. Matches' aspirations were far too ambitious and this has apparently been mismanaged since the acquisition by Apax. Well done to Tom and Ruth Chapman for coming out when they did. »

But what other problems did these online giants face that contributed to their decline?

Costs/investment

The costs of selling online, delivering and possibly processing an item back are not negligible. And for luxury operations in particular, trying to offer an experience that goes beyond what the customer might get at ASOS or Zalando increases costs. All those Net-A-Porter branded vans, those marbled Matches boxes, those priority VIP phone lines and other VIP services, that detailed product information, every item photographed on a mannequin rather than an avatar, delivery in 90 minutes and all of this costs money. DRGlobalata's Price told us: "Frasers Group's decision to close Matches so soon after acquiring the business suggests it underestimated the scale of the investment and the time required to oversee a recovery. Although Frasers successfully turned around luxury retailer Flannels after acquiring it in 2017, Matches' online specialization would have presented Frasers with unusual challenges that it would not have had the expertise or ability to easily resolve, the most of its portfolio being multi-channel. Selling luxury online is particularly difficult, given that buyers generally prefer to try and see expensive products in person before purchasing. »

Making customers feel special...all customers

There are many reviews online of long phone times, botched deliveries, and late refunds at online luxury retailers. This is also true for peers further down the price scale. But the difference is that consumers are less forgiving when they pay 900 pounds than when they pay 24.99 pounds. As hard as they try, it's a daunting challenge for online retailers to replicate the luxury physical store experience online, especially at a time when consumers are enthusiastically embracing brick-and-mortar stores again.

Many online retailers are going all out to target the biggest, biggest spending customers, and it makes sense. Mytheresa CEO Michael Kliger recently told Fashionnetwork.com that its top 3.8% customers account for almost 39% of the company's revenue. But aspiring customers cannot be neglected and he admitted that reaching them was increasingly difficult.

Those of us who don't have an endowment like to feel like our 500 book order is really important to a company even though they also handle orders in the tens of thousands. And a major problem for luxury e-commerce today is that this customer has many other choices, rather than buying the high-end designer shoes that might have cost 350 pounds 20 years ago but cost now more than double that amount (although inflation should have meant they cost 'only' £375).

So where are they going? Towards premium brands like those belonging to SMCP, or Zadig et Voltaire, Whistles, etc. To discount centers in Europe, such as those owned by VIA Outlets. Towards the clearance sales of designer stores and department stores. And online, they are heading to the booming second-hand market.

Andy Mulcahy, director of strategy and insights at IMRG, told us that this is the biggest problem plaguing online luxury sales and will persist even after the cost of living crisis is a distant memory. Price of DR

He said: “People have really started to use C2C options in the last 12 months, particularly Vinted. Indeed, Collect+ says that [Vinted] now represents a significant portion of their volume. If you can find premium brands out there, second hand but still in good condition, I think that creates real competition for that type of brand. »

And of course, the same goes for the many high-end resale sites, like Vestiaire Collective, where a buyer could perhaps pick up a mint condition Bar Dior jacket (MSRP £3,500) for around £1,200, or a product from a smaller brand for perhaps 20% of its new price.

Rebound in physics

We cannot ignore the fact that physical retail has been brought back to life in unexpected ways. Demand for luxury spaces on streets like Bond Street, Avenue Montaigne, Via Monte Napoleone, Fifth Avenue, Dubai Mall and others is strong.

Retailers, from giant luxury department stores to individual brands, are going all out to attract customers to their stores and are also linking their physical stores with their online operations to create omnichannel experiences than pure-play online retailers (or even quasi pure players like Matches or Farfetch via its Browns property) cannot compete.

This means that online commerce faces enormous challenges even without the business-specific issues. As Mulcahy told us: “There’s no doubt that the [online] market is in a real state. Post-pandemic, [in the UK] we have had two years of declining growth (-10% in 2022, -3% in 2023) with a forecast of 0% for this year [but] January started at -7 %. The health and beauty industry is doing great, most other categories are struggling, and fashion is among the worst. Growth reached -6% in 2023 for clothing, compared to a forecast of 0%. » These numbers will likely be repeated in many key luxury markets.

Brand relations

All of this creates a lot of pressure for online retailers and stocking the right brands is crucial if they are to have any chance of success. The industry faced huge difficulties in the early days attracting brands who felt e-commerce simply wasn't the right environment for them. And some problems persist. Recently, the parent company of END. Clothing published annual results in which it said it was “affected by the withdrawal of key brand franchises”.

Brand relationships were an issue at Matches too and when Sky News revealed the administration's filing it said some brands had started to cut ties with the company due to late payments and demands for discounts.

As for Farfetch, before the company's sale, Richemont said its brands would not open expected online dealerships on the site, while Neiman Marcus and Kering both cut ties. In fact, the owner of Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and others recently said that e-commerce as a whole was declining as a percentage of total group sales and that Kering's direct brand exposure on Farfetch was limited. This was not only a bad sign for Farfetch but for online luxury retail in general. This meant that one of the leading owners of luxury brands was essentially saying that e-commerce was not a priority for him.

Logistics

It’s not just about brands as efficient logistics operations are also crucial. Logistical problems faced by luxury names have also shown that the high end is not immune to the problems that have hit sellers of more affordable products like Boohoo, ASOS and Dr. Martens. Again, END's experience. is an extreme example of this.

To minimize the impact on customers, this had to reduce marketing and promotional activities to slow down website traffic. Actively dissuading buyers from buying is not a recipe for growth!

Overconfidence

When Frasers Group bought Matches, it said it had “incredible relationships with its brand partners” and “we are confident that by leveraging our industry-leading ecosystem, we will unlock synergies and drive profitable growth ".