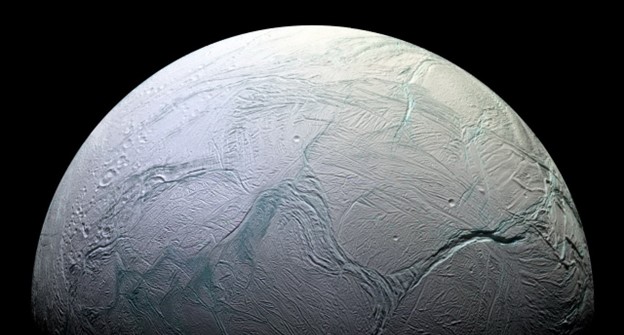

The surface of Enceladus is covered with a dense layer of snow.

Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, is cloaked in a heavy snow covering that reaches depths of 700 meters in certain areas, according to recent research.

Planetary scientist Emily Martin draws humorous comparisons between Enceladus and Buffalo, the notoriously snow-laden city in New York. She remarks that the significant depth of the snow insinuates that the remarkable plume of Enceladus may have been much more active in the past. This is a conclusion drawn from the study Martin and her team detailed in the Mar. 1 Icarus, a scientific journal.

Since the Cassini spacecraft discovered their existence in 2005, Enceladus' geysers, which consist of water vapor and other compounds, have captivated the interest of planetary scientists. They postulate that the spray probably originates from a salty ocean located under an icy shell.

While a portion of the water forms one of Saturn's rings, the majority of it descends back onto the surface of the moon as snow, as maintained by Martin. A greater understanding of the properties of this snow, including its depth and density, could shed light on the moon's past history. This knowledge is crucial for planning future missions to Enceladus.

Martin, employed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., emphasizes the need to comprehend the terrain for future mission planning, stating, "If you're going to land a robot there, you need to understand what it’s going to be landing into.”

To determine the depth of the snow on Enceladus, Martin and her team took cues from our planet, specifically Iceland. Iceland has geological structures known as pit chains, which are lines of indentations in the ground formed when loose rock, ice or snow falls into a fissure underneath. Similar features appear across the solar system, including on Enceladus.

Prior research had proposed a method of employing geometry and sunlight angles to measure the depth of the pits, which would then provide an estimate of the depth of material that the pits are situated in. Fieldwork carried out in Iceland in 2017 and 2018 led Martin and her colleagues to believe that this same approach could be applied to Enceladus.

Their findings, derived from images captured by the Cassini spacecraft, revealed that the thickness of the snow varies across Enceladus, reaching up to 700 meters depth in some areas.

Martin acknowledges the baffling question of how such an abundance of snow could have accumulated on the moon's surface. A theory that the plume's spray has remained the same since the origin of the solar system would require 4.5 billion years to deposit such a significant volume of snow on the surface. Even then, the snow density would have to be exceptionally high.

Martin finds it unlikely that the moon's plume was instantly activated upon the moon's formation and has remained constant since. Even if this was the case, later layers of snow would compress the initial layers, densifying them and making the total snow layer less deep than currently measured.

According to Martin, this might suggest that the plume was significantly more active in the past, thereby depositing a greater amount of snow in a shorter period. She concludes, "You need to crank up the volume on the plume.”

Another scientist, Shannon MacKenzie of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, admired the ingenuity of the technique. She states that without physical presence on the moon's ground, it's difficult to directly measure the snow's depth. She commends the authors for skillfully utilizing geological interpretations as their exploratory tools.

MacKenzie, who did not participate in this new research, led a separate study investigating potential future missions to Enceladus. A remaining question from that study pertains to potential landing sites for a spacecraft. The study conducted by Martin and her colleagues can provide helpful insights in terms of ruling out specific locations that may be too unstable due to deep and loose snow.