Woman Discovers Live Python Parasite in Her Brain, Doctors Confirm

The woman’s mysterious symptoms started in her stomach.

Weeks of abdominal pain and diarrhea led to night sweats and a dry cough. Then, doctors found lesions on her lungs, liver, and spleen. An infection, perhaps. But tests for bacteria, fungi, a human parasite, and even autoimmune disease all came up negative.

Three weeks later, the woman was in the hospital with a fever and cough. CT scans revealed a clue that was telling, in retrospect: Some of her lung lesions appeared to be migrating. A second clue came months later, when the woman became forgetful and depressed. “She had a very astute GP who thought, ‘Something’s not right here, I better do an MRI of the brain,’” says Sanjaya Senanayake, an infectious disease physician at the Australian National University and the Canberra Hospital.

That brain scan turned up a ghostly glow in her frontal lobe. It could have been cancer, an abscess, or another affliction, Senanayake says. “No one thought it was going to be a worm.”

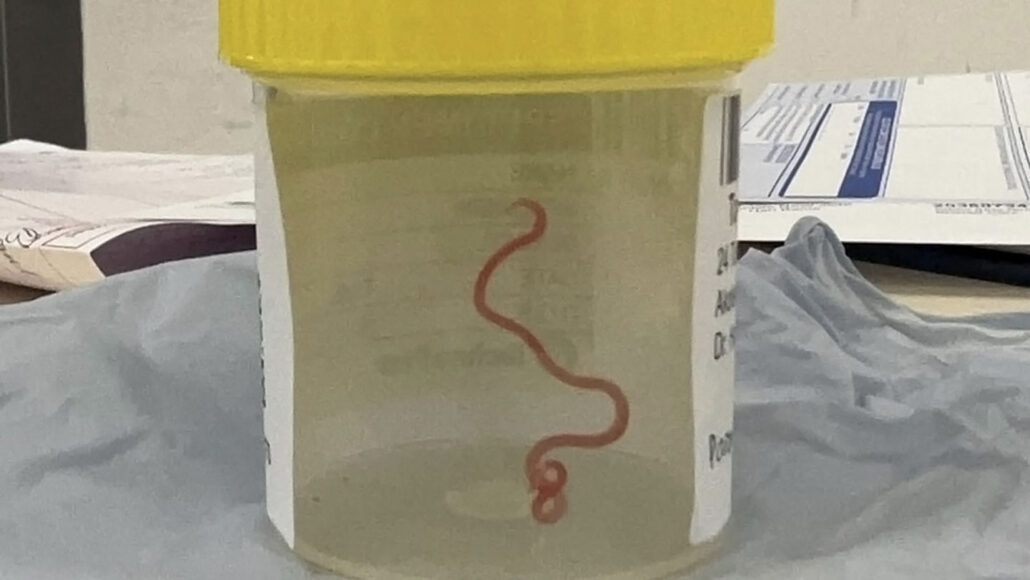

During a biopsy of the woman’s brain, her neurosurgeon spotted a suspicious stringlike structure and plucked it out with forceps. It was pinkish-red, about half the length of a pencil — and still alive.

“It was definitely one of those ‘wow’ moments,” Senanayake says. “A worm in the brain!” But the doctors also felt relieved. It meant they had a diagnosis, he says. The team finally would know how to treat its patient.

The worm, Ophidascaris robertsi, was a nematode whose main host is a snake, Senanayake and his colleagues report in the September Emerging Infectious Diseases. The woman, who lives in New South Wales, Australia, is the first documented case of an infection in humans.

“The live wriggling worm was … what got everyone so interested,” Senanayake says, “but there’s a more important side to it.” O. robertsi is a parasite that jumped from wild animals to a human. As human and animal populations overlap, he says, “we’re starting to see more and more of these spillover infections.”

The parasite that doctors found in the woman’s brain was far from its usual home. These worms typically shuttle between snakes and small mammals. Adult worms live inside carpet pythons (Morelia spilota), which shed worm eggs in their feces. Rats or possums, for example, can ingest the eggs, which grow into larvae that burrow into flesh. Pythons then eat the infected animals, and the cycle continues.

Humans and most other animals exist outside this loop — though in 2019, scientists reported one case of O. robertsi in a koala. It’s not clear exactly how the woman in Senanayake’s study became infected, but doctors suspect she may have accidentally consumed worm eggs camouflaged in some edible plants. She lived near a lake inhabited by carpet pythons and would often collect native warrigal greens, which people commonly use for salads or stir-fries.

The eggs probably hatched in her body, spawning larvae that wandered to her organs, causing damage along the way. O. robertsi worms “do not have teeth, but they do migrate through tissue, destroying it,” says Meera Nair, an infectious disease scientist at the University of California, Riverside who studies hookworms and other parasitic worms. The python parasite secretes substances that can dissolve proteins and tissues.

Those lesions doctors saw on the woman’s CT scans were probably due to migrating larvae and the body’s resulting inflammation, Nair says. She thinks it’s almost certain the worm was to blame for the woman’s sudden neurological symptoms.

Senanayake’s team couldn’t find any previous examples of O. robertsi invading other animals’ brains. But other worms do.

Different species of roundworms can live inside rats and raccoons and even people’s pets (SN: 7/30/18).

These parasites can infect people and worm their way into the brain — and such infections have occurred in people living in the United States, says Jill Weatherhead, an infectious disease doctor and parasitologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Toxocara worms parasitize cats and dogs, which may poop in backyards, sandboxes, or public parks, spreading eggs where children play. “This is why veterinarians encourage deworming,” she says.

If kids munch on contaminated sand, larvae can hatch in their bodies like they would in a dog or cat. But in people, the larvae won’t end up in the intestines and develop into adults. Instead, they’ll get stuck in other tissues.

Like O. robertsi worms, Toxocara larvae can rattle the stomach and inflame the organs. Doctors have reported cases where the worms meandered up to a person’s eye. “Even though we are accidental hosts,” Weatherhead says, the parasite “can still cause significant disease in humans.”

Though human cases of brain-burrowing roundworms are rare, infections in general may be relatively common. One study estimated that about 1 in 20 people in the United States have been exposed to Toxocara.

But the true number is hard to pinpoint, Weatherhead and her colleagues wrote August 23 in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. Their analysis of Toxocara cases at a children’s hospital in Texas suggested that kids living in low-income areas were more likely to be infected — particularly in areas with stray dogs and cats.

“We shouldn’t be fearful,” Weatherhead says, but it’s important to focus on prevention, especially as humans encroach on other animals’ habitats.

Senanayake agrees: “If you handle vegetation or wildlife, just make sure you wash your hands,” he says. “And if you’re cooking and consuming vegetation, make sure you cook it well, just to reduce the chance of one of these unusual infections.”

He remembers one unusual case about 20 years ago of a parasite in a young man who swallowed a slug and developed an unusual form of meningitis. Like that man, the woman with the worm will be hard to forget. “Finding a live parasite in the brain is something … you don’t necessarily expect to encounter in your career,” Senanayake says.

After surgery, doctors treated the woman with antiparasitic medications, and her symptoms have since improved. When told about the worm, she was “obviously not thrilled,” he says. But like her doctors, she was relieved to finally have a pathway to treatment.

Our mission is to provide accurate, engaging news of science to the public. That mission has never been more important than it is today.

As a nonprofit news organization, we cannot do it without you.

Your support enables us to keep our content free and accessible to the next generation of scientists and engineers. Invest in quality science journalism by donating today.