I ricercatori scoprono che le immagini superconduttive sono in realtà frattali 3D guidati dal disordine.

12 maggio 2023

Questo articolo è stato sottoposto alla procedura editoriale e alle politiche di Science X. Gli editori hanno messo in risalto i seguenti attributi, garantendone la credibilità del contenuto:

- verificati i fatti

- pubblicazione sottoposta alla revisione dei pari

- fonte affidabile

- corretta la bozza

a cura di Cheryl Pierce, Purdue University

Soddisfare le domande di energia mondiali sta diventando un punto critico. L'alimentazione dell'età tecnologica ha causato problemi a livello globale. È sempre più importante creare superconduttori che possano operare a pressione e temperatura ambientali. Ciò contribuirebbe molto a risolvere la crisi energetica.

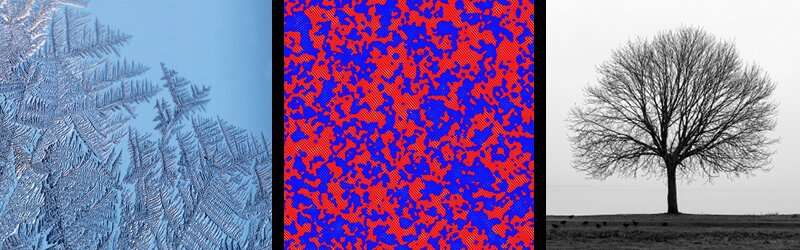

Gli sviluppi della superconduttività dipendono dagli avanzamenti nei materiali quantistici. Quando gli elettroni all'interno dei materiali quantistici subiscono una transizione di fase, gli elettroni possono formare motivi intricati, come i frattali. Un frattale è un motivo che non finisce mai. Quando si fa zoom su un frattale, l'immagine appare uguale. I frattali comunemente visti possono essere un albero o il gelo su una finestra in inverno. I frattali possono formarsi in due dimensioni, come il gelo su una finestra, o in uno spazio tridimensionale come i rami di un albero.

La prof.ssa Erica Carlson, professore di fisica e astronomia al 150 ° anniversario presso la Purdue University, ha guidato un team che ha sviluppato tecniche teoriche per caratterizzare le forme frattali che questi elettroni creano, al fine di scoprire la fisica sottostante che guida i motivi.

Carlson, fisico teorico, ha valutato immagini ad alta risoluzione delle posizioni degli elettroni nel superconduttore Bi2-xPbzSr2-yLayCuO6 + x (BSCO), e ha determinato che queste immagini sono effettivamente frattali, scoprendo che si estendono in uno spazio tridimensionale occupato dal materiale, come un albero che riempie lo spazio.

Ciò che una volta era considerato come dispersions casuali all'interno delle immagini frattali è ora di millennio e, sorprendentemente, non è dovuto ad una transizione di fase quantistica sottostante come previsto, ma a causa di una transizione di fase guidata dal disordine.

Carlson ha guidato un team di ricercatori collaborativi in diverse istituzioni e ha pubblicato i loro risultati, intitolati "Correlazioni nematiche critiche in tutto il campo di doping superconduttivo in Bi2-xPbzSr2-yLayCuO6 + x", in Nature Communications.

Il team include scienziati di Purdue e istituti partner. Da Purdue, il team include Carlson, il dott. Forrest Simmons, recente studente di dottorato, e i dott. Shuo Liu e Benjamin Phillabaum. Il team di Purdue ha completato il suo lavoro all'interno del Purdue Quantum Science and Engineering Institute (PQSEI). Il team di istituti partner include il dott. Jennifer Hoffman, il dott. Can-Li Song, il dott. Elizabeth Main dell'Università di Harvard, il dott. Karin Dahmen dell'Università di Urbana-Champaign e il dott. Eric Hudson della Pennsylvania State University.

"L'osservazione dei motivi frattali delle entità di orientamento ('nematiche') - estratti in modo ingegnoso da Carlson e collaboratori da immagini STM delle superfici di cristalli di un superconduttore ad alta temperatura a cuprato - è interessante e esteticamente attraente di per sé, ma anche di notevole importanza fondamentale per affrontare la fisica essenziale di questi materiali", afferma il dott. Steven Kivelson, il professore della famiglia Prabhu Goel presso la Stanford University e un fisico teorico specializzato in nuovi stati elettronici nei materiali quantistici. "Una qualche forma di ordine nematico, comunemente considerata un avatar di un ordine di densità di carica più primitivo, è stata ipotizzata come giocare un ruolo importante nella teoria dei cuprati, ma le prove a favore di questa proposta sono state precedentemente ambigue. Seguono due importanti deduzioni dall'analisi di Carlson et al.: 1) Il fatto che i domini nematici appaiono frattali implica che la lunghezza di correlazione, la distanza sulla quale l'ordine nematico mantiene la coerenza, è maggiore rispetto all'area visibile sull'esperimento, il che significa che è molto grande rispetto ad altre scale microscopiche. 2) Il fatto che i motivi che caratterizzano l'ordine sono gli stessi ottenuti da studi del modello di Ising a campo casuale tridimensionale - uno dei modelli paradigmatici della meccanica statistica classica - suggerisce che l'estensione dell'ordine nematico è determinata da quantità estrinseche e che intrinsecamente (cioè in assenza di imperfezioni cristalline) esibirebbe una maggiore correlazione di fascia non solo lungo la superficie, ma si estenderebbe profondamente all'interno della massa del cristallo ".

High resolution images of these fractals are painstakingly taken in Hoffman's lab at Harvard University and Hudson's lab, now at Penn State, using scanning tunneling microscopes (STM) to measure electrons at the surface of the BSCO, a cuprate superconductor. The microscope scans atom by atom across the top surface of the BSCO, and what they found was stripe orientations that went in two different directions instead of the same direction. The result, seen above in red and blue, is a jagged image that forms interesting patterns of electronic stripe orientations.

'The electronic patterns are complex, with holes inside of holes, and edges that resemble ornate filigree,' explains Carlson. 'Using techniques from fractal mathematics, we characterize these shapes using fractal numbers. In addition, we use statistics methods from phase transitions to characterize things like how many clusters are of a certain size, and how likely the sites are to be in the same cluster.'

Once the Carlson group analyzed these patterns, they found a surprising result. These patterns do not form only on the surface like flat layer fractal behavior, but they fill space in three dimensions. Simulations for this discovery were carried out at Purdue University using Purdue's supercomputers at Rosen Center for Advanced Computing. Samples at five different doping levels were measured by Harvard and Penn State, and the result was similar among all five samples.

The unique collaboration between Illinois (Dahmen) and Purdue (Carlson) brought cluster techniques from disordered statistical mechanics into the field of quantum materials like superconductors. Carlson's group adapted the technique to apply to quantum materials, extending the theory of second order phase transitions to electronic fractals in quantum materials.

'This brings us one step closer to understanding how cuprate superconductors work,' explains Carlson. 'Members of this family of superconductors are currently the highest temperature superconductors that happen at ambient pressure. If we could get superconductors that work at ambient pressure and temperature, we could go a long way toward solving the energy crisis because the wires we currently use to run electronics are metals rather than superconductors. Unlike metals, superconductors carry current perfectly with no loss of energy. On the other hand, all the wires we use in outdoor power lines use metals, which lose energy the whole time they are carrying current. Superconductors are also of interest because they can be used to generate very high magnetic fields, and for magnetic levitation. They are currently used (with massive cooling devices!) in MRIs in hospitals and levitating trains.'

Next steps for the Carlson group are to apply the Carlson-Dahmen cluster techniques to other quantum materials.

'Using these cluster techniques, we have also identified electronic fractals in other quantum materials, including vanadium dioxide (VO2) and neodymium nickelates (NdNiO3). We suspect that this behavior might actually be quite ubiquitous in quantum materials,' says Carlson.

This type of discovery leads quantum scientists closer to solving the riddles of superconductivity.

'The general field of quantum materials aims to bring to the forefront the quantum properties of materials, to a place where we can control them and use them for technology,' Carlson explains. 'Each time a new type of quantum material is discovered or created, we gain new capabilities, as dramatic as painters discovering a new color to paint with.'

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Purdue University