A Refined Drug Target Offered by Mapping the Evolution of E. Coli's Main Virulence Factor

June 15, 2023

This article has undergone review as per Science X's editorial process and policies. The editors have emphasized the following characteristics while ensuring the authenticity of the content:

- fact-checking

- peer-reviewed publication

- trusted source

- proofreading

- by Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

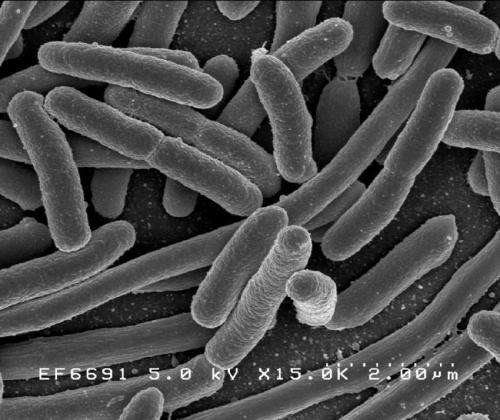

A group of researchers, comprising a multi-center team led by the University of Oslo, Imperial College London, the Wellcome Sanger Institute and UCL, has, in a new study published in Nature Communications, mapped for the first time the evolutionary timeline and population distribution of the outer capsule of Escherichia coli, a protective cover that is responsible for the bacterium's virulence. The study indicates how targeting the bacterium's protective layer can assist in treating extraintestinal infections.

The investigation focused on a particular subset of E. coli, which has a specific capsule that scientists have named K1. E. coli with this particular capsule are known to cause invasive illnesses like bloodstream, kidney infections, and meningitis in newborns. This super-coating allows E. coli to mimic molecules already present in human tissues, thereby allowing it to enter the body without any notice.

The researchers present evidence that targeting the capsule can be used as the basis of a cure, enabling prevention of serious E. coli infections. E. coli is a leading cause of urinary tract and bloodstream infections, which can cause mortality rates as high as 40% in premature and term newborns when it causes meningitis. The increase in hypervirulent and multiple-drug resistant E. coli over the past decade has made the development of effective strategies to prevent and cure these infections an urgent necessity.

Comprehending the bacterium's anatomy, and its role in causing illnesses, is crucial for preventing serious infections. To date, lack of basic knowledge about the prevalence, evolution, and functional properties of the K1 capsule has limited scientists' ability to fight E. coli infections.

Researchers at the University of Oslo, Imperial College London, UCL and the Wellcome Sanger Institute have now mapped the evolution of this E. coli strain, its distribution and prevalence. They carried out an analysis of 5,065 clinical samples from different countries and time periods using high-resolution population genomics, whole genome sequencing, and advanced computational tools. The data included big collections of samples from Norway and the UK, newly obtained adult and neonatal samples from six different countries, including Brazil, Mexico and Laos among others, and samples from the pre-antibiotic era, dating back to 1932.

A finding of the study is that the virulent capsule K1 actually dates back approximately 500 years earlier than previous estimates. This highlights the importance of the capsule to the bacterium's survival and the role of the extracellular barrier in E. coli's success as the primary cause of extraintestinal infections.

Dr. Sergio Arredondo-Alonso, the lead author of the study from the University of Oslo, and the Wellcome Sanger Institute said, "It was exciting to discover the possibility of reconstructing the evolutionary history of the K1 capsule over the last half millennium, and to see how the capsule genes have been acquired over and over again by many different lineages of this pathogen species over the centuries. As neither the prevalence nor the history of K1 was known, it felt like we entered truly unchartered territory and significantly advanced understanding of this major pathogen species."

The research also found that 25% of all E. coli strains responsible for bloodstream infections today contain the genetic information they need to develop the K1 capsule. Obtaining a full evolutionary history of this strain will enable scientists to understand how bacteria acquire the genetic material responsible for severe virulence in the first place and analyze ways to fight them.

Using bacteriophage enzymes, which are viruses that infect and kill bacteria, the researchers could remove the bacterium's extracellular barrier, making it vulnerable to the human immune system. The researchers demonstrated in vitro experiments using human serum that targeting this capsule can cure E. coli infections broadly without using antibiotics, which is consistent with previous experimental infections in animals.

Dr. Alex McCarthy, a senior author of the study from Imperial College London, said, 'We specifically demonstrated the advances made possible by combining experimental microbiology with population genomics and evolutionary modeling tools, to open a window into translating the findings into future clinical practice. We show that therapeutic targeting of the K1 capsule makes these pathogens more vulnerable to our immune system, and offers the possibility of preventing serious infections. For example, it could help treat newborn babies with meningitis caused by K1 E. coli, which is a rare but dangerous condition associated with high mortality and serious long-term adverse health effects.'

Professor Jukka Corander, a co-senior author of the study from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Oslo, said, 'Our research shows the importance of representative genomic surveys of pathogens over time and space. These studies will enable us to reconstruct the evolutionary history of successful bacterial lineages and pinpoint changes in their genetic make-up that can lead to their ability to spread and cause disease. Such knowledge is ultimately providing the basis for designing future interventions and therapies against these pathogens.'