Climate change endangers the life cycle of 'sea butterflies' and poses a threat to the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

May 11, 2023

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

- fact-checked

- peer-reviewed publication

- trusted source

- proofread

by Frontiers

The world's oceans absorb approximately a quarter of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. During absorption, CO2 reacts with seawater and oceanic pH levels fall. This is known as ocean acidification and results in lower carbon ion concentrations. Certain ocean inhabitants use carbon ion to build and sustain their shells. Pteropods, which are important components of the marine ecosystem, are among them.

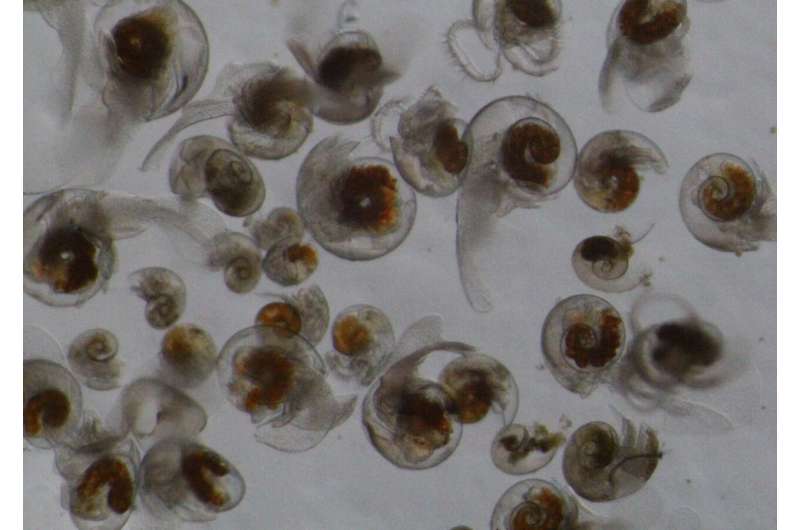

Certain aspects about pteropods, including life cycles and population dynamics, are not well-studied. This is partly due to their size—some sea butterfly species measure less than a millimeter—and poor long-term survival in captivity. Now, a team of marine scientists has examined life cycles, abundance, and seasonal variability of shelled sea butterflies in the north-east Scotia Sea, a region undergoing some of the fastest climate change in the Southern Ocean.

'Decline in Antarctic Ocean pteropod populations could have cascading ramifications to the food web and carbon cycle,' said Dr. Clara Manno, a researcher at the British Antarctic Survey and corresponding author of the study published in Frontiers in Marine Science. 'Knowledge about the life cycle of this keystone organism may improve prediction of ocean acidification impacts on the Antarctic ecosystem.'

For their work, the scientists collected sea butterflies in a sediment trap, a sampling device moored at 400 meters depth. 'It is impossible to observe the full life cycle of sea butterflies in a laboratory setting, so we had to piece together information about their spawning, growth rate and population structure,' added Dr. Vicky Peck, a researcher at the British Antarctic Survey and co-author of the study. 'Using sediment trap samples, we successfully reconstructed their life cycle over a year.'

For the two dominant species collected—Limacina rangii and Limacina retroversa—the scientists observed contrasting life cycles, leading to different vulnerabilities to changing oceans. L. rangii, a polar species, can be found as both adults and juveniles during the winter months. L. retroversa, a subpolar species, appear to occur only as adults during the winter.

During the coldest season, ocean water is more acidic than during other times of the year because cooler temperatures increase CO2 dissolution in the ocean. The life stages of sea butterflies that exist then are more exposed and vulnerable to increased levels of ocean acidification, the researchers wrote.

The fact that L. rangii adults and juveniles coexist over winter may give them a survival advantage. If one cohort is vulnerable, the overall population stability is not at risk. With L. retroversa, however, if one cohort is removed, the whole population may be vulnerable.

The researchers noted that despite species being impacted differently, neither is likely to remain unharmed if exposed to unfavorable conditions for extended time periods.

As the intensity and duration of ocean acidification events increase, they begin to overlap with spawning events in the spring. This may put the most vulnerable life stage, the larvae, particularly at risk and could jeopardize future populations, the scientists warned.

To learn how such a scenario might play out in the Scotia Sea, the research team will continue to study sea butterflies dwelling there. 'A next step will be to focus on multiyear sediment trap samples to identify potential inter-annual variability in the life cycle associated with environmental change,' said Dr. Jessie Gardner of the British Antarctic survey, lead author of the study.

Journal information: Frontiers in Marine Science

Provided by Frontiers