Delving into the Menace of Staph Aureus: A Drug-Resistant Superbug

February 20, 2025

feature

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

by Delthia Ricks, Phys.org

British physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming, discoverer of penicillin nearly 100 years ago, was the first to warn of the dangers of antibiotic resistance.

In his 1945 Nobel Prize speech, 27 years after his breakthrough discovery, Fleming put the world on notice foretelling a potentially dark future for his miracle drug in the event of abuse or overuse of the medication. It was a warning that spelled trouble ahead for a vast segment of the pharmacopeia known as antimicrobial drugs.

Now, microbiologists in Hungary and China are collaborating on ways to predict drug resistance among strains of Staphylococcus aureus when exposed to antibiotics in the drug development pipeline—drugs that have yet to reach the marketplace.

Similar research was underway in the United States, involving S. aureus and multiple other bacterial species, but it was halted by the transition into the Trump administration.

S. aureus is the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of the microbial world. It exists harmlessly on the skin and in nasal passages, a commensal bacterium that is part of the human microbiome. But it also exists as a drug-resistant pathogen, and microbiologists have found that many of these bacteria are resistant to multiple antibiotics.

Worse, the collaborative team in Hungary and China is issuing both a renewal of Fleming's earlier warning and a 21st century twist on his concern. Pathogenic S. aureus strains are not only resistant to many antibiotics on pharmacy shelves, but they quickly gain resistance to antibiotic candidates in the developmental pipeline, repelling medications before they're even tested in humans.

'The continuous rise of antimicrobial resistance is a serious global concern and has been compared to a pandemic,' writes Dr. Ana Martins of the Synthetic and Systems Biology Unit at the Biological Research Center in Szeged, Hungary. Martins is lead author of a new antibiotic resistance study published in Science Translational Medicine.

'Several antibiotic candidates are in development against Gram-positive bacterial pathogens, but their long-term utility is unclear,' Martins continued, noting that antibiotics in development can be made worthless before they reach the pharmaceutical marketplace. Multiple bacterial species in general—and multiple variants of S. aureus in particular—are genetically endowed to quickly overpower the drugs.

All S. aureus strains are part of the large group of bacterial species referred to as Gram-positive because of the way they react to laboratory stains, such as crystal violet. They are distinguished from Gram-negative bacteria—a veritable rogues gallery of pathogens—by the thickness of their cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglygan wall and appear purple when stained; Gram-negative bacteria turn pink.

Staph aureus is immediately recognizable when viewed under a microscope: clusters of spherical bacteria that, when stained with crystal violet, appear reminiscent of clusters of grapes. Unstained, they are the same clustering spheres, but yellow-golden in color, hence the name 'aureus,' Latin for golden.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

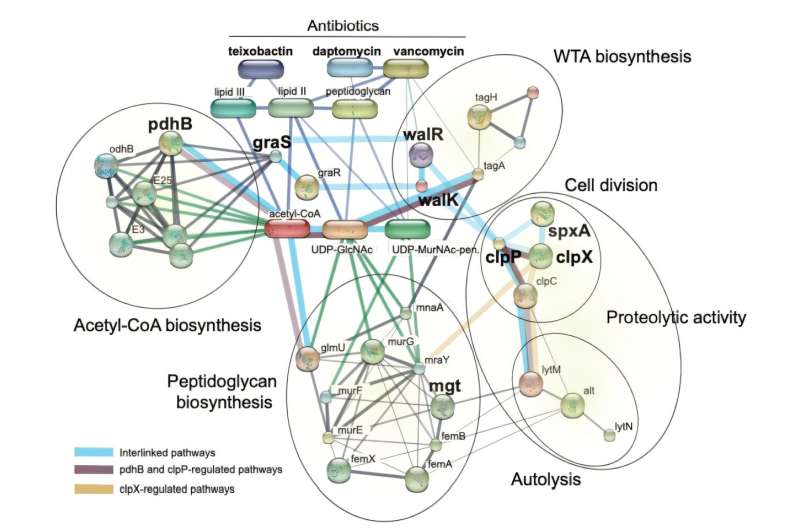

The research by Martins and her team of collaborators was designed to pinpoint the biological mechanisms that prompt resistance. The research also tackled another question: Why are some newly approved antibiotics initially successful but prove problematic, in some instances, under the neutralizing power of S. aureus?

'A prime example is dalbavancin, a treatment option for patients infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA,' Martins asserted.

'Despite approximately a decade of intensive research and substantial funding, resistance to dalbavancin emerged within a short period of just two years after its commercialization, jeopardizing the entire undertaking and underscoring the precarious nature of combating bacterial resistance.'

To understand the capacity of S. aureus to become a drug-resistant menace, it is important to note that it is part of an enormously complex family. More than 30 types of Staphylococcus bacteria have been identified.

While S. aureus thrives harmlessly on the skin and in the upper respiratory tract, pathogenic S. aureus can be a potent cause of skin and bloodstream infections, pneumonia, food poisoning, endocarditis, bone infections and toxic shock syndrome.

It's pathogenic dark side is the result of virulence factors that allow it to bypass stalwart immune system defenses, especially when cuts or other deep wounds breach the skin and deeper tissues. Each bacterial cell also carries multiple mobile genetic elements, Martins and colleagues underscored, that allow it to quickly adapt to new environments and gain new traits.

To determine whether they could predict the emergence of antibiotic resistance, Martins and colleagues examined how S. aureus interacted with eight experimental and recently approved antibiotics. The team also analyzed why S. aureus repelled well-established medications, such as dalbavancin.

The team discovered that resistance could be predicted based on gene mutations that are present in the overall population of S. aureus, the result of an abundance of mobile genetic elements that can be shared within bacterial colonies.

When Martins and her collaborators exposed the bacteria to the medications, the microbes were able to handily defeat the drugs. Antibiotic resistance apparently developed from the selection of preexisting genetic variants, the team found.

'We compared the resistance profiles of three antibiotics with a long clinical history with those of five antibiotics currently in development or that have recently been introduced into clinical practice,' Martins explained. 'The recent antibiotics demonstrate potent activity against a range of Gram-positive bacteria and serve as potential treatment options for infections caused by drug-resistant S. aureus.'

With the exception of one antibiotic, which was still in the research phase, a drug known as SCH79797, S. aureus rebuffed every experimental and recently approved antibiotic tested by the team of researchers. Scientists were surprised that S. aureus repelled two candidate antibiotics, afabacin and teixobactin, despite great hope for their success.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the medical world's most pressing challenges, according to the World Health Organization, and a reason that Martins and colleagues compared the resistance crisis as a pandemic. No region of the world has been left unscathed by antibiotics that are failing to defeat resistant bacteria.

The WHO has gone on record declaring the problem so critical that drug resistance will become a leading cause of death by 2050 unless solutions are developed now.

A discouraging situation highlighted in the research paper is the lack of a robust number of antimicrobials in the drug-development pipeline. Pharmaceutical companies worldwide have discontinued their antibiotic research programs, leaving clinicians with few options. The next best step, Martins and colleagues say, is evaluating the medications before they're approved for widespread use.

'Our work highlights the importance of predicting future evolution of resistance to antibiotic candidates at an early stage of drug development,' Martins concludes.

More information: Ana Martins et al, Antibiotic candidates for Gram-positive bacterial infections induce multidrug resistance, Science Translational Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adl2103

Journal information: Science Translational Medicine

© 2025 Science X Network