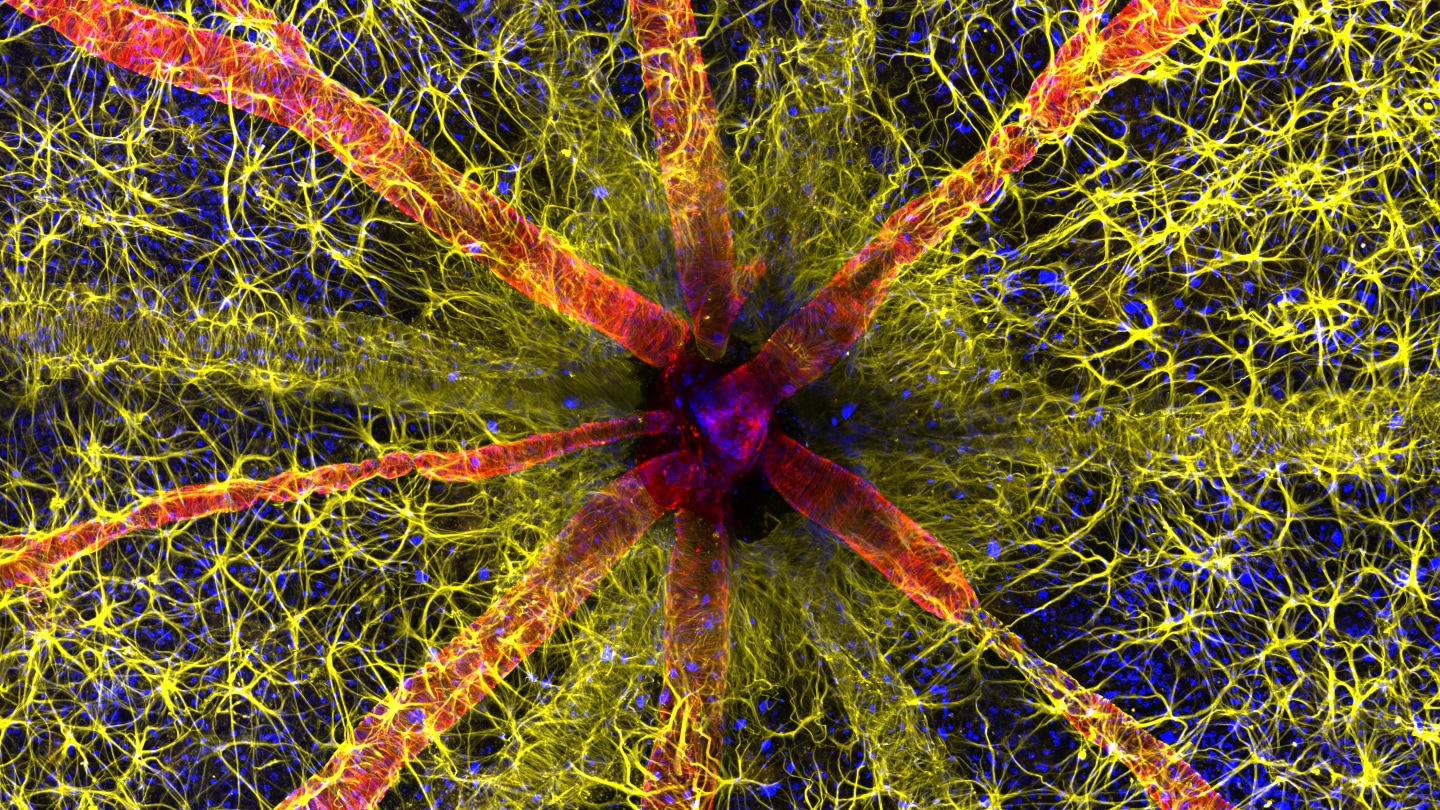

Nikon Small World photo contest winner showcases intricate details of a rat’s eye

An eye full of cellular stars is a stunning example of the beauty that exists in nature’s smallest sizes.

A glimpse of the back of a rat’s eye, and the immune cells that keep it healthy, won first place in the 2023 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition. The image, composed of multiple snapshots captured with a confocal microscope, was taken by neuroscientist Hassanain Qambari of the Lions Eye Institute’s Centre for Ophthalmology and Visual Science in Perth, Australia.

Tap this image and those below to enlarge

The photo is artificially colored to showcase the eye’s optic nerve — the black spot in the center — and surrounding structures in the retina, a layer of cells within the eye that captures light. A protein that helps blood vessels contract is shown in red and cell nuclei are blue. In yellow are astrocytes, a kind of immune cell that helps control inflammation in the retina.

The image is part of research that aims to uncover how diabetic retinopathy — a disease where high blood sugar damages retinal blood vessels — can alter the function and structure of the retina, Qambari says. When people are diagnosed, the disease is typically already in a late stage and the retina has sustained irreversible damage. Some people can go blind.

By pinpointing any changes that happen early on, researchers may be able to develop a drug to reverse those changes before the disease advances and causes damage.

The inner workings of the rat eye is one of 86 photos recognized in this year’s competition, the winners of which were announced October 17. Here are a few of our other favorites.

Some of these cells are in fix-it mode.

The photo, snapped by molecular physiologist Vaibhav Deshmukh, showcases cells called myoblasts that build muscle. These myoblasts are from mice and can be grown indefinitely in lab dishes. With dyes and antibodies, Deshmukh, then studying heart myoblasts as a graduate student at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, marked different parts of the cells in blue, orange and magenta.

One cell, in the image’s center, is in metaphase, a stage of the cycle that divides a single cell into two. During metaphase, the nucleus dissolves, and DNA-carrying chromosomes line up in the center of the cell. In the next step of the cycle, the chromosomes will be pulled apart. The image shows “how a dividing cell changes its shape and navigates through a crowded space to complete the cell cycle,” Deshmukh says.

In the body, myoblasts kick into high gear when muscle is damaged. Muscle fibers can’t repair themselves after injuries like sprains and cuts. Instead, myoblasts fuse to the fibers to help muscle regenerate.

Allergy sufferers, beware — this photo may cause phantom itchiness or sneezing.

Educator John-Oliver Dunn of Bendorf, Germany, took more than 600 images to piece together a view of sunflower pollen on an acupuncture needle. Dunn wanted to showcase how small pollen is relative to a needle, first attempting to take photos with an insulin needle. But as acupuncture needles have a finer point, they hold the pollen better, Dunn says.

A sunflower is not actually a single flower. The brown center of just one is filled with hundreds of tiny flowers. The male flowers of this bunch are responsible for the pollen, sprouting long filaments covered in pollen for insects to pick up and take to other plants.

Bright butterflies often steal the spotlight from duller-colored moths. But the scales on this Chinese moon moth (Actias ningpoana) are snatching it back.

Photographer Yuan Ji snapped this photo of a dead moth in his studio at the World Expo Museum in Shanghai. Many photographs focus on moon moths’ flashiest features: spots that adorn their wings or long tentacle-like extensions. But Ji zoomed in on a different spot at the top border of the insect’s left wing.

Microscopic butterfly and moth scales give the insects their wing decor, which can sometimes help the organisms blend into their surroundings to hide from predators. For Ji, the scales resemble cars on a road.

Biologists Priscilla Vieto Bonilla and Brandon Antonio Segura Torres spent days shadowing one amphibian egg from zygote to hatch day.

What emerged was this small axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), shown at 1 week of age. Axolotls are salamanders native to just two lakes in Mexico, one of which no longer exists and another that has been reduced to mainly canals. The young creature will retain its youthful features throughout its life, a phenomenon called neoteny, Vieto Bonilla says.

It’s unclear why the animals look forever young, but it may be because their native lakes never dried up, at least not before Spanish colonizers started draining lakes near present-day Mexico City to control flooding in the 1600s. Other amphibians that live in areas with transient streams or lakes mature from water-living young into adults capable of thriving on land or in water. But year-round access to lakes may have helped axolotls hold onto larvae-esque features, such as gills, that allow them to stay in water full time.

The pair of photographers, both undergraduates at the Universidad Nacional del Comahue in San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina, were delighted to watch a new life develop. “While studying the theory in the classroom is one thing,” Vieto Bonilla says, “observing the zygote dividing in real time was an entirely different experience.”

This article was supported by readers like you. Invest in quality science journalism by donating today.