Four Essential Facts About Advanced Nuclear Reactors and Their Unique Uranium Requirements

Nuclear power of the future is going to need fuel. That has governments, energy companies and nuclear engineers clamoring to get their hands on HALEU: high-assay low-enriched uranium.

HALEU (pronounced like “Hey, Lou”) was previously a niche material, used mainly in nuclear reactors conducting scientific research. But now, multiple companies in the United States have proposed newfangled types of nuclear reactors that they claim will generate electric power more efficiently and safely. Such reactors, many of which will run on HALEU, are a key part of the United States government’s plan to meet future demands for clean energy. On June 10, TerraPower, a company founded by Bill Gates, broke ground on what is to be one of the first of this new generation of HALEU-fueled reactors. But currently, the United States doesn’t make that fuel in the amounts that will be needed by that cohort. So while the U.S. Department of Energy is funding the development of such advanced reactors, it is also working to secure an ample supply of HALEU fuel.

But some scientists are raising concerns about the rise of HALEU. According to a commentary in the June 7 Science, HALEU could be used to make a nuclear weapon, something not possible with current reactor-grade fuel.

HALEU’s potential for providing power, and the weapons worries that may come along with it, raise pressing questions. Here are four things to know about HALEU.

Compared with standard reactor fuel, HALEU contains a larger proportion of a key variety of uranium, the isotope uranium-235. U-235 is fissile: Its nucleus splits into two upon absorbing a low-energy neutron, releasing energy in the process.

Naturally occurring uranium contains only about 0.7 percent U-235. Most of the remainder is the isotope U-238. To be used in a nuclear power plant, uranium must be enriched to contain more U-235. Standard reactor-grade uranium contains about 3 to 5 percent U-235. Uranium enriched to 20 percent or above is known as highly enriched uranium, which, unlike reactor-grade uranium, can be used to make nuclear weapons.

HALEU falls between those two extremes, with around 5 to 20 percent U-235. That means it can be used in ways that reactor-grade uranium can’t, but the United States and other countries don’t restrict its use as tightly as highly enriched uranium.

The HALEU hoopla has been fueled by the interest in advanced nuclear reactors. That term lumps together a wide variety of reactor designs that don’t fit the standard mold for reactors in the United States. Advanced reactors are often smaller than typical reactors and may use a substance other than normal water for cooling, such as liquid sodium. And advanced reactors commonly require HALEU, typically enriched to just under 20 percent.

With HALEU, “you’re able to make the core smaller and more energy-efficient in the space that you have, thus reducing construction costs,” says nuclear engineer Josh Jarrell of Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho Falls. And HALEU fuel can be used in forms that differ from the uranium dioxide fuel used in current reactors. Some reactor designs use a metallic fuel, or poppy seed–sized coated pellets of uranium called TRISO. The different fuel options and different reactor designs can be a plus for safety, Jarrell says. “Depending on the design, they don’t actually require human involvement to shut down safely.”

At the moment, most advanced reactors in the United States exist only on paper. But DOE is funding two advanced reactor demonstration projects: TerraPower’s Natrium Reactor in Kemmerer, Wyo., and X-energy’s Xe-100 Reactor in Seadrift, Texas. Both require HALEU.

There’s no established, large-scale commercial supplier of HALEU in the United States. And no matter how advanced a reactor is, it’s useless without fuel. Russia produces HALEU, but a U.S. law passed in May will prohibit most importation of uranium from Russia.

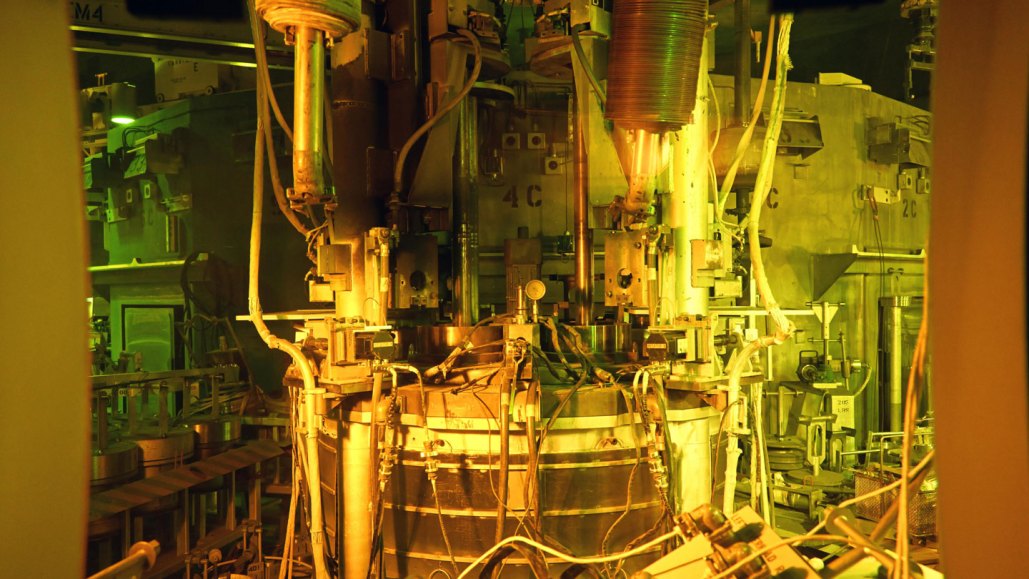

To ensure that advanced reactor projects have fuel, the U.S. government has been supporting efforts to produce the material. A Maryland-based company, Centrus Energy Corp., has begun producing some HALEU as part of a demonstration project in collaboration with DOE at an enrichment facility in Piketon, Ohio.