Flash reveals supermassive black hole orbiting larger one

A long-suspected black hole may have finally come out of hiding.

A monstrously massive black hole in a distant galaxy probably has a smaller companion that orbits it every 12 years. But that tiny partner has never been detected. Now, astronomers claim to have seen a flash of light coming directly from the smaller black hole for the first time.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before,” said astronomer Mauri Valtonen on June 7 at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Albuquerque.

Astronomers have been watching this object since the 1880s, when it showed up in a survey of asteroids as a brilliant point of light. That point of light, now dubbed OJ287, is a blazar. Among the brightest-looking objects in the universe, blazars are supermassive black holes that launch bright jets of radiation into space, and those jets happen to point almost directly at Earth. This one sits about 3.5 billion light-years away.

Sometimes, OJ287 shines even brighter than usual. For the past 40 years or so, astronomers have noticed that the object has a dramatic jump in brightness every 11 to 12 years.

In 1996, Valtonen and his colleague Harry Lehto, both of the University of Turku in Finland, suggested that the outbursts could be due to one supermassive black hole orbiting an even more massive black hole. Both black holes are probably behemoths, the astronomers calculated: The smaller is around 150 million times the mass of the sun, and the bigger is around 18 billion solar masses. For perspective, the black hole in the center of the Milky Way is about 4 million solar masses (SN: 5/12/22).

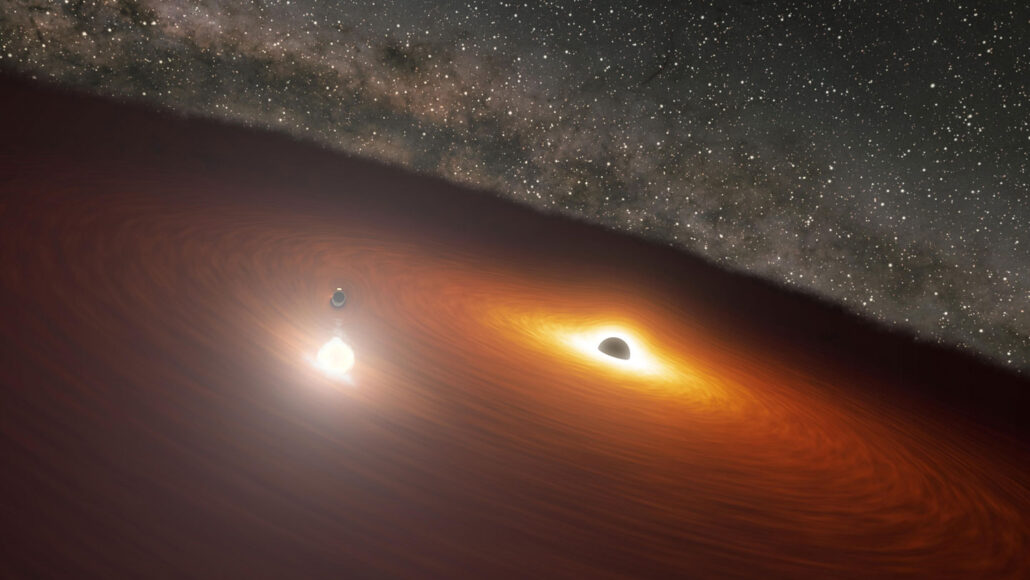

The bigger black hole is thought to be surrounded by a disk of white-hot gas and dust, which glows at many wavelengths of light. If the smaller black hole exists, then every time it plunges through that disk, it would trigger a flash of light — thus explaining the recurring outbursts.

But until now, no light had been detected from the second black hole itself. Its presence was merely inferred from those regular flares.

Valtonen and his colleagues predicted that the most recent flare should arrive in January or February 2022 and arranged to monitor OJ287 every day using telescopes on Earth and in space. The team saw flares like the ones they had seen before, but there was a new flare that was different. It was bright and quick, fading after one night.

The team proposed that this flare came from a jet created by the smaller black hole pulling material out of the disk as it approached, before the collision.

“It swallows a whole lot of disk matter,” Valtonen said. “That matter falls into the secondary black hole, and you get a huge flare.”

Previous observations missed that flare because it is so short. The team almost missed it in 2022, due to bad weather. “We never observed OJ287 night to night to night [before], this was the first time,” he said. “That’s why we saw it.”

Get great science journalism, from the most trusted source, delivered to your doorstep.

Some researchers have suggested other ways for a single black hole to give off the same pattern of light. If the team’s interpretation is correct, then it marks the first time the second black hole has been seen directly, Valtonen says.

“The detection of the second black hole should put an end to this discussion,” he says. “More generally, this could be the beginning of work on secondary jets in binary black hole systems, which could open up a new research field, now that we have at least one concrete example to study.” If other binary black holes make similar flashes as the smaller black hole crosses the larger one’s disk, astronomers now know how to look for them.

The observations do suggest the presence of a second black hole, says Caltech astronomer Seppo Laine, although other ideas are still possible.

“Mauri has been basically pushing this supermassive black hole binary model for decades now,” Laine says. “It doesn’t completely confirm it, but if this interpretation is correct, then it’s a significant step forward.”

Unfortunately, it may be difficult to test. The short flares come only once a decade, so astronomers need to be ready the next time. To resolve the two black holes directly, Valtonen says, might take a radio telescope in space.