Uncovering the Unusual Actions of Male Fruit Flies in Bright Lighting Scenarios

August 28, 2023

feature

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

- fact-checked

- peer-reviewed publication

- trusted source

- proofread

by Stephanie Baum, Phys.org

A recent study published in Open Biology reports that exposure to intense light almost instantly provokes courtship behavior in male fruit flies (Drosophila). Surprisingly, the researchers observed both male-male and male-female courtship behavior under these conditions. While male-male courtship behavior among fruit flies is not a new discovery, the findings of this study suggest that intense light exposure specifically precipitates it.

A research team including members from the Department of Biology and the Iowa Neuroscience Institute at the University of Iowa and from the Department of Biological Sciences at University of Alabama made this discovery while observing the general behavior of male fruit flies in intensely-lit test arenas.

Earlier studies have found that internal drive, previous experiences, and sensory input from external sources—including gustatory, olfactory, visual, and mechanosensory signals—all factor into male courtship behavior toward receptive females in Drosophila melanogaster. Male flies typically make a show of chasing, licking, extending their wings, and using them to produce courtship 'songs' before ultimately mounting the targeted females.

Similar male-male courtship behavior has appeared among mutant flies in previous research involving manipulation of specific genes, but this new study began with observations of wild-type Drosophila melanogaster from two different strains.

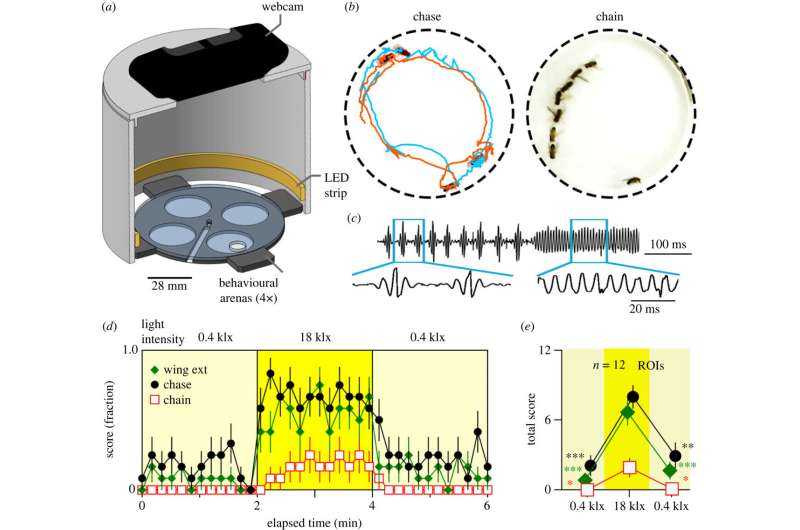

Using arenas specially equipped with adjustable LED lighting, microphones, webcams, and a fly tracking system, the team ran multiple experiments to observe the flies' behavior.

Beginning with flies in male-only groups, the researchers measured their activity under varying light intensities, beginning with an exposure time of two minutes at 0.4 kilolux (abbreviation: klx, which approximates a normal room lighting level), then increasing to 18 klx for another two minutes, and then another two minutes at 0.4 klx. To test the effects of non-LED light sources, they also ran similar tests using incandescent light at a peak intensity of 25 klx and sunlight at a peak of 90 klx.

Among the notable results in experiments across the light sources, flies from both strains began their courting attempts within seconds after the light came on, and their activity heightened considerably during exposure to the brightest light levels. In each strain of flies, the researchers observed wing extension, chasing, and also 'chaining' behavior—in which the flies formed a line—previously only seen among mutants in other studies.

The flies also produced male-male courtship songs with features similar to those of songs produced during male-female courtship. The research notes a relationship between song production and wing extension induced by light.

The researchers additionally tested whether high-intensity light exposure would unleash similar courtship behaviors in mixed-gender groups, and their results were similar to those observed in male-only groups.

After running tests on the wild-type flies, the team sought to understand how different sensory systems might be involved in light-triggered male-male courtship, and looked at flies with a range of mutations. Among completely blind mutants exposed to intense light, they noted no courtship activity. Visually impaired (but not completely blind) mutants missing the R7 central photoreceptor for UV light also failed to exhibit male-male courtship under intense light.

Males with certain mutations of the white gene, lacking visual screening pigments (a condition that leads to increased light sensitivity but degraded image processing ability), displayed locomotion in the test arena but did not specifically court other males. Similarly, the team observed decreased male-male courtship behavior by eye-color mutants with bright orange eyes and white eyes.

In contrast, the research highlights that alterations to auditory and mechanosensory cues in the form of wing cuts did not change the affected flies' ability to produce courtship song, and they were able to participate in chasing and chaining. Even flies with a single wing were able to achieve wing extension frequency close to that of wild-type flies.

Mutant male flies with diminished and completely absent olfactory abilities provided particularly surprising results. At lower light levels, their male-male courtship behaviors measured higher than those of wild-type males—so high in flies of diminished olfactory ability, in fact, that any behavioral increases they might have shown could not be measured during intense light exposure. Those who were completely smell-blind exhibited milder increases during low-light exposure, and thus the team was able to measure increases in their activities during peak light intensity periods.

When the team examined male-female courtship behaviors among smell-blind and smell-diminished males, they found similar results.

Overall, the research suggests that exposure to intense light heightens courtship behavior of male fruit flies toward both females and other males, but does not switch their sex preference. Furthermore, the findings also indicate that unimpaired visual processing is likely critical to intensified courtship behavior under high light levels, and that further examination of the role of olfactory processing in the courtship behavior of male Drosophila may provide a broader understanding of this topic.

Journal information: Open Biology

© 2023 Science X Network